Parts of Southeast Asia have been hit by typhoons and experienced severe floods over the past weeks, causing a still-mounting death toll and displacing millions. Green Left’s Peter Boyle spoke to Suresh Kumar, head of the environmental bureau of the Socialist Party of Malaysia (PSM), about the causes and solutions.

* * *

What do you think is behind this crisis?

The main driver of this crisis is the rapid warming of the surrounding seas, a trend that is especially pronounced in Asia. The waters around countries severely affected by these floods, including Sri Lanka, Indonesia, Thailand and Malaysia, are warming at nearly twice the global average.

Warmer seas lead to significantly higher evaporation, which increases atmospheric humidity and produces larger, more moisture-laden rain clouds. These clouds then feed and intensify thunderstorms. As these storm systems move from the sea toward land, they carry excessive moisture, resulting in far heavier and more prolonged rainfall than normal.

This pattern aligns with regional climate data showing that the Indian Ocean and western Pacific are among the world’s fastest-warming ocean regions, creating ideal conditions for extreme rainfall events and severe flooding.

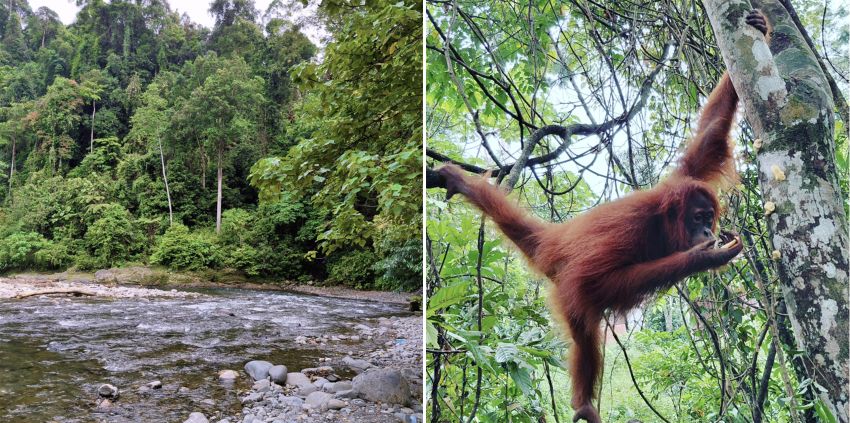

However, excessive rainfall alone does not explain the scale of destruction. The impact is made significantly worse by extensive forest clearing in countries like Indonesia and Malaysia. This has been evident in the huge mudslides, muddy floodwater with debris carrying logs during recent disasters.

For example, in Malaysia, although official statistics claim a high percentage of forest cover (54%), the definition used by agencies is neither transparent nor ecologically accurate. For example, in places, oil palm plantations are classified as “forest”, and in states like Kelantan, about 50% of the forest coverage is actually “production forest”, areas open for logging. Such degraded landscapes cannot absorb heavy rain or stabilise soil, turning intense rainfall into catastrophic floods and landslides.

This combination — rapid ocean warming driving extreme weather and weakened terrestrial ecosystems unable to buffer the impact — is at the heart of the current crisis.

What has been the response of governments in the region and is this meeting public expectations?

Government responses across the region have been swift at the operational level, particularly in search and rescue, but major gaps remain in climate-disaster preparedness, early-warning systems and long-term infrastructure planning.

Sri Lanka stands out for its decisive action. With more than 600 deaths, hundreds more missing and more than a million people displaced, the government declared a state of emergency, mobilised the military nationwide and immediately appealed for international assistance. India and Japan responded within hours, supplying personnel and equipment. Sri Lanka’s willingness to trigger global support early prevented the situation from worsening.

Indonesia, however, has faced strong criticism, despite a death toll now exceeding 900 lives. Civil society groups, disaster experts and environmental organisations point out that the national response has been poorly coordinated, with slow mobilisation, fragmented authority between central and regional governments and delayed rescue operations — some areas reportedly waited up to 72 hours for aid.

President Prabowo Subianto’s remark that climate change is a problem Indonesians “have to confront” fell short of acknowledging the scale of the crisis, and unlike Sri Lanka, no national emergency was declared nor international assistance requested.

Environmental groups such as WALHI [Indonesia’s Friends of the Earth] and Greenpeace Indonesia criticised the government’s chronic unpreparedness, weak enforcement against deforestation, and the absence of integrated disaster-risk planning. The Indonesian Disaster Experts Association and academics from UI and UGM also highlighted outdated flood maps, insufficient early-warning coverage in rural areas and a generally reactive national disaster framework. These systemic failures significantly worsened the scale of loss.

Thailand, with more than 150 deaths, also faces questions similar to Indonesia regarding its level of preparedness. Although search and rescue efforts by the military and local authorities were prompt, concerns persist about ineffective early-warning systems, structural weaknesses in floodgates and river embankments and incomplete implementation of national flood-mitigation master plans that have been pending since the 2011 mega-flood. Several affected communities reported receiving alerts only after waters had risen, revealing gaps in communication and infrastructure readiness.

Malaysia’s response has been adequate at the operational level, with search-and-rescue mobilised to a reasonable degree. However, the larger question remains unanswered: Where are the results from the billions of ringgit allocated for flood-mitigation projects over the past decade? Transparency and accountability on drainage upgrades, river-widening works and enforcement against illegal land clearing are still lacking.

Overall, while frontline rescue teams across all countries deserve praise, the deeper issue lies in the absence of sustained, well-financed and accountable climate-disaster mitigation efforts. The region’s warming seas and intensifying rainfall demand far more than reactive measures — they require governments to confront long-standing structural failures in environmental management, preparedness planning and climate adaptation.

What measures does the PSM propose to respond to this crisis and to prepare for similar such crises in the future?

Short-term solutions include providing rapid, unconditional support to displaced households and vulnerable groups: free shelter, food, medical treatment and psychosocial support (mental health and trauma care).

Safe drinking water, sanitation, hygiene, electricity/gas and communications need to be restored as fast as possible; and the supply of emergency goods (fuel, medicines, hygiene kits) to affected areas needs to be maintained.

We need transparent, independent investigations into all reports of illegal logging, mining, deforestation or destructive land use in affected watersheds. Suspicious permits should be immediately suspended; investigations should be fully disclosed to the public; and where laws were breached, there should be prosecutions.

The region should mobilise international solidarity to send aid, expertise and funding, especially to poorer countries or under-resourced regions that lack capacity.

The climate crisis is not just a technical issue, but a matter of climate justice. The countries of the Global North, which historically emitted most greenhouse gases, bear much greater responsibility. Yet, the worst impacts now fall on Global South nations in Asia, low-lying, densely populated and heavily dependent on vulnerable ecosystems. Therefore, national and regional policies should press for global climate reparations, loss and damage financing and binding commitments from major emitters.

At the same time, Asian countries must themselves strengthen domestic climate mitigation: reducing carbon emissions, shifting to renewable energy and imposing carbon taxes or pollution levies on industries that heavily emit greenhouse gases, so the polluters pay, locally and globally.

Regional institutions like the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) should be used to implement a coordinated climate resilience policy. Climate impacts transcend national borders, so collective regional action is essential.

However, during this year’s term as ASEAN chair, Malaysia failed to push through a region-wide carbon-pricing or carbon-tax framework across ASEAN member states. Given that the next chair next year is the Philippines, the bloc should use that opportunity to finally institutionalise a harmonised carbon price or equivalent levy across ASEAN to avoid “race to the bottom” for foreign investment and to level up shared responsibility.

Flood mitigation, drainage, river management and coastal defence projects should not be treated as purely “engineering solutions”. Instead, each project must be reexamined for cost effectiveness, environmental sustainability and social impact. Local communities, independent experts, ecologists and civil society organisations must be involved from the planning stage.

The billions spent over past decades, whether in Malaysia, Indonesia, Thailand or elsewhere, must be audited for efficacy, transparency and maintenance. Mitigation funds should not be hidden under opaque “emergency budgets” that are rarely audited, which often leads to cost overruns, corruption and poor upkeep.

Our governments urgently need to fund stormwater systems, retention basins and permeable surfaces in towns and cities, prioritising low-income areas.

Permits for land conversion, logging, plantation expansion and mining — especially in headwater zones, forested hills or steep slopes — must be strictly reviewed and regulated. Legislatures in each country should mandate that state level leaders, land resource directors and forestry officials be held legally accountable, even criminally, if they approve environmentally destructive permits that later fuel floods or landslides.

Independent, multi-stakeholder institutions (including civil society, government, scientific experts and ordinary citizens) should be set up at the state/provincial level and given veto power over dangerous land use permits.

We need large-scale reforestation, mangrove restoration, upstream watershed rehabilitation, peat-forest protection and wetland revival. These are nature-based solutions that absorb rainfall, reduce runoff, stabilise soil and act as natural flood buffers.

Protecting coral reefs and coastal ecosystems also help moderate storm surges and sea level rise. Governments should prioritise long-term ecosystem health over short-term commercial land conversion.

[Governments must] develop and deploy robust early warning, monitoring and community-based disaster systems and set up reliable flood, landslide and storm surge early-warning systems. [These should] use real time hydrological and meteorological data, remote sensing, community sensors and timely communication (SMS, radio, community-based alerts).

[They should] train local communities in disaster preparedness, evacuation plans, build local shelters, designate safe evacuation routes, and maintain community-level emergency response teams.

[There is a need to] make early-warning data publicly accessible and multilingual and ensure that vulnerable groups (rural, poor, remote) are included in outreach and drills.

ASEAN (or a sub-regional grouping) could establish a shared disaster risk and adaptation fund — financed by environmental levies, carbon taxes or fossil fuel export windfall taxes — to support cross-border disaster relief, reconstruction, ecosystem restoration and climate adaptation.

We also need to encourage social protection schemes across the region: flood and disaster insurance for smallholders/farmers, unemployment or relocation support for displaced people, disaster resilient social housing, public health and mental health support for affected communities and the provision of alternative livelihoods for workers displaced from climate disaster.

While the richest countries in the Global North are mostly responsible for global warming, most of the costs of the impacts are in countries in the Global South. What do you think should be done about this gross imbalance?

The United States alone accounts for 40% of excess emissions and the European Union, 29%. Collectively, industrialised countries account for 90%.

At the same time, from 1990 to 2015, the Global North extracted an estimated $242 trillion in net resources from the South, a structural drain that has limited the South’s fiscal space to adapt to the very crisis it did not cause. Those who caused the crisis bear primary responsibility for resolving it, and this must translate into binding obligations.

High-income nations owe an estimated US$192 trillion in climate reparations from now to 2050, or roughly US$6.4 trillion per year. This is affordable: research shows this could be financed through a 3.5% annual wealth tax on the richest 10% of the Global North.

Global South negotiators must unite to demand that rich nations decarbonise much faster in line with their fair shares of the remaining carbon budget. Current pledges by the European Union, US, Canada, Japan and Australia allow them to continue overshooting their fair shares. This forces the Global South to decarbonise faster and at greater cost, an injustice that must be compensated through substantial resource transfers, technology cooperation and financial guarantees. The South cannot continue subsidising the North’s slow transition.

Today, around 50% of the materials consumed in the Global North are net-appropriated from the South. Their renewable energy industries, manufacturing supply chains, electronics, pharmaceuticals, agriculture depend on imported minerals, labour and ecological capacity from Africa, Asia and Latin America. This dependency gives the South real leverage.

Global South countries can form resource and commodity cartels, coordinate export standards tied to climate obligations, demand fair prices, debt relief and technology transfers and threaten strategic restrictions if climate commitments are not honoured.

The existing global financial system dominated by the US dollar and Western-controlled institutions locks the South into debt, high interest rates and dependency on imported technology.

To break this cycle, Global South countries should establish currency swap lines with China and other partners to obtain renewable energy technologies outside imperialist currencies, expand participation in BRICS-linked development banks and South-South technology exchanges and build regional climate financing institutions within ASEAN and other blocs.

This could allow Global South countries to invest in solar, wind, storage and green manufacturing without exposing themselves to Western conditionality or unequal exchange.

We can build domestic and regional climate resilience without repeating patterns of exploitation. While the North must take primary responsibility, the South must also ensure its own transitions do not replicate internal inequalities.

To achieve this, the Global South countries must negotiate as a bloc in global platforms.

COP 30 has just concluded in Brazil. From a Southeast Asian perspective, do you consider it a failure?

Southeast Asia is a region already suffering the frontline impacts of climate breakdown, while contributing little to the historical emissions driving it. The core failures are no fossil-fuel phase-out, no emissions [reduction] roadmap and no accountability. Expectations ahead of COP30 were high because more than 80 countries supported Brazil’s call for a formal, binding roadmap to phase out fossil fuels.

Similarly, the summit failed to include a roadmap for reversing deforestation. It produced no major new emissions-reduction pledges, with around 80 of 194 countries failing to submit updated targets for 2035 and it left the world on a trajectory of 2.6°C warming by 2100.

The blame lies primarily with wealthy, high-emitting nations that have repeatedly blocked a fossil-fuel phase-out, refused to reduce emissions in line with their fair share, resisted the scale of climate finance required and protected fossil-fuel and corporate interests above global survival

Even the Baku to Belém Roadmap, aimed at scaling climate finance to US$1.3 trillion annually, was not endorsed; the COP30 decision merely “takes note” of it, without adopting any of its mechanisms.

For Southeast Asia, COP30’s outcome amounts to a profound political failure.