Of all the international institutions established in the aftermath of World War II, the Council of Europe is, perhaps, the one most explicitly dedicated to creating a better society. It was established to defend three things: democracy, human rights and the rule of law. Observing the world around us, it is difficult to credit it with much success, yet we continue to lobby its politicians and bureaucrats and organise demonstrations outside its gates.

At every meeting of the council’s Parliamentary Assembly, Kurds and their supporters come to talk and protest about Turkey, the member state that, since the departure of Russia, occupies the biggest part of the council’s time.

All council members sign the European Convention on Human Rights and accept the European Court of Human Rights as superior to their national courts. The European Court’s rulings are binding, but they are not enforceable. The council has no police force, but they can limit a state’s role within the council, or, ultimately, expel them. Internal sanctions send a very negative message about the nature of a state.

There have been a large number of rulings against Turkey in the European Court, but when it comes to the most politically significant, Turkish authorities refuse to comply. Each year, the council’s Committee of Ministers — consisting of the foreign ministers of member states or their deputies — discusses Turkey’s refusal to implement the changes demanded, and each year they defer taking real action and give Turkey more time to respond.

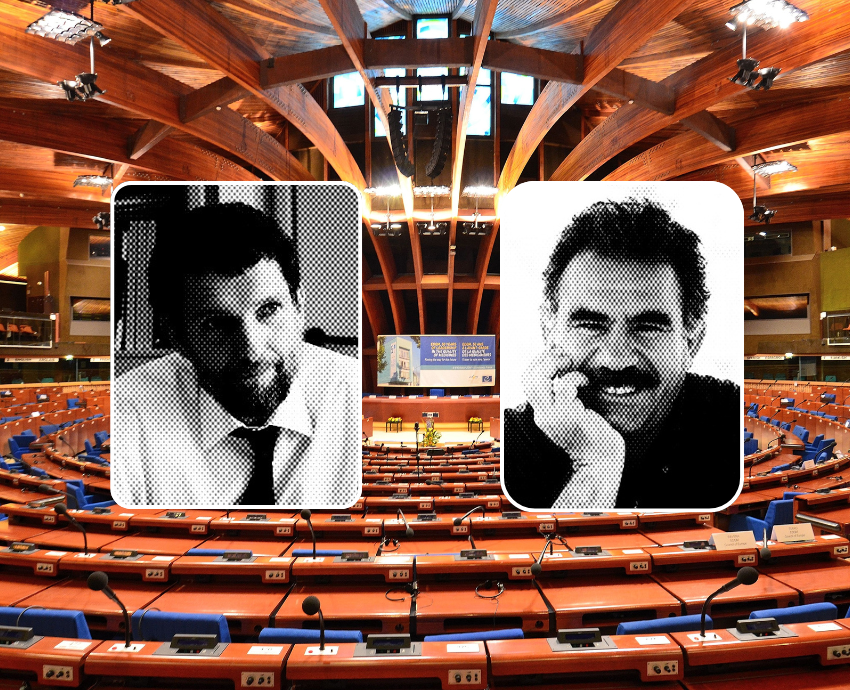

The latest example of kicking the ball into the long grass took place in September, when the Committee of Ministers discussed Turkey’s failure to comply with the court’s 2019 rulings to release the businessman-philanthropist Osman Kavala, and the former co-chair of the Peoples’ Democratic Party (HDP) — now the DEM Party — Selahattin Demirtaş. These cases have implications for other cases, such as those of the HDP’s other co-chair, Figen Yüksekdağ, whose case is more recent, and of Can Ataly, elected MP for the Turkish Workers’ Party, whose case is related to that of Kavala.

Öcalan’s Right to Hope

The Committee of Ministers also discussed Turkey’s refusal to grant imprisoned Kurdish leader Abdullah Öcalan his “Right to Hope”, as demanded by the European Court in 2014. All prisoners are expected to have a right to be considered for parole, usually after a maximum of 25 years, but when Turkey abolished the death penalty in its attempt to get acceptance into the European Union, Öcalan’s sentence was commuted to a living death of imprisonment without end. This type of sentence is regarded as torture, but has since been applied to more than 4000 political prisoners in Turkey.

There is a notable reluctance at the council to engage with Öcalan’s case. Although universal rights are, by definition, applicable to everyone, it was not until seven years after the court’s ruling that the Committee of Ministers addressed Turkey’s non-compliance.

The implications of this reluctance go way beyond Öcalan’s individual situation. It undermines the integrity of the court; it ensures the continued denial of rights to the other political prisoners that Turkey has incarcerated for life without parole; and it maintains a major hurdle in front of the tentative peace process with the Kurds.

Öcalan was the leader of the Kurdistan Workers’ Party, now officially dissolved but still waiting for an agreement that would allow its guerrillas to disarm and be incorporated into democratic politics.

To negotiate peace, it is vital to talk to the people who have been doing the fighting — especially when, as in Öcalan’s case, they have been calling for a peace agreement for more than three decades. Öcalan’s leadership is also recognised much more widely, by millions of Kurds across the world. To carry out his vital negotiating role he needs to be free to meet with and talk to many different people and not be kept locked away in an island prison with limited access.

Attacks on democracy

The ongoing negotiations in Turkey over the future of the Kurdish struggle have raised a cautious optimism among Kurdish politicians and activists, though we have yet to see concrete actions from the government side.

But there can be no real peace without democracy. Even if, as anticipated, legislative changes begin to be introduced, hopes for democracy seem to be increasingly confounded by the Turkish government’s attempts to use their compromised judiciary to destroy political opposition.

In recognition of the ongoing negotiations, the target of the government’s lawfare attacks has moved from the DEM Party to the main opposition Republican People’s Party (CHP) — though there has been no respite for HDP/DEM Party politicians and activists already deposed or imprisoned. This shift is clearly intended not only to destroy the CHP but also to destroy improved relations between the more social-democratic wing of the CHP and the DEM Party.

One achievement of the negotiations has been the establishment of a cross-party parliamentary commission to examine the legislative issues. The Committee of Ministers recognised this as a possible mechanism for implementing the outstanding European Court rulings, but there are concerns that the committee could also be tempted to use the existence of the commission as another delaying tactic.

It was also worrying to see the Committee of Ministers quoting the Turkish government’s framing of the ongoing process as a “‘terror-free Türkiye’ initiative”. For the Kurds it has always been, as Öcalan stated, about “Peace and a Democratic Society”.

The Turkish government’s assault on the CHP prompted an “urgent” debate in the autumn session of the Council of Europe’s Parliamentary Assembly, held on September 29, which discussed “Democracy, rule of law and inclusive dialogue in Türkiye”.

The assembly meets four times a year and is made up of MPs from all the different national parliaments in proportion to their party’s representation in those parliaments. Apart from speakers from Turkey’s ruling Justice and Development Party and one far-right deputy who used the debate as a hook for his own grievances, condemnation of Turkey’s attack on democracy was universal.

It was, though, disappointing to observe that CHP speakers failed to acknowledge that what was happening to them had happened to the DEM Party first. Nevertheless, the debate gave a strong message: but that was all. There was not even a motion and a vote.

Inaction

Council of Europe officials in various departments also engage in many discussions behind the scenes, and these can be more effective than public statements, but actual progress towards putting real pressure on Turkey remains glacial.

Why this is the case is only too obvious, and was spelt out in the speech of the Left Group co-chair in the debate on the progress report at the beginning of the session. Laura Castels told the chamber that “we confirm that in this Parliamentary Assembly the agenda is more and more monopolised by geopolitical-motivated issues — especially after the invasion of Ukraine by Russia … We should avoid double standards, and we should be consistent in how we react in backslidings in each case.”

When it comes to Turkey, European states have many reasons not to want to upset the government. They want to ensure that Turkey — which has used its strategic position to flirt with both Washington and Moscow — stays within the NATO camp; they want to maintain their business interests, not least in the arms trade; and they rely on the European Union agreement with Turkey to keep migrants out of European Union countries. As we see again and again, absence of democracy is only cited as a political factor when this is useful to push another agenda.

Of course, there has been a great deal of questioning of international institutions recently. If they cannot stop a genocide happening in front of our eyes, what good are they?

The Council of Europe has also been frighteningly slow to acknowledge the gravity and the reality of Israel’s genocide in Gaza. The council is made up of the same politicians that have failed to act in their own countries, so perhaps we should not be surprised, but it is specifically a human rights organisation.

There has been a slow awakening over Gaza, but the initial debates and the continued lack of action have been deeply shameful.

Why lobby?

So why should we continue to lobby the Council of Europe? The answer needs to be multi-layered.

Even while we criticise the council for the limits of its approach and the failure to achieve its aims, its existence as an organisation for human rights can help provide a framework for engaging with the building of a better society. We rightly decry hypocrisy, but Donald Trump’s United States demonstrates the nightmare of destroying all notion of shared political ethics.

And although actual achievements are small, they are not negligible. Every debate we can help inform can contribute to bringing issues into public view and make it a little harder for governments to act with impunity.

However, those governments can also see that the so-called “international community” are letting them get away with their actions.

Our engagement with international organisations such as the Council of Europe also serves the perverse function of demonstrating that we have to do more than lobby political leaders: that the changes we need won’t be handed down from above and that there is no shortcut that can bypass organised pressure from below.

That pressure can force governments and international organisations to act beyond elite interests. It can also go further and change the very nature of our institutions and allow us to escape their limited worldview.

[Sarah Glynn is a writer and activist — visit her website and follow her on X or Bluesky.]