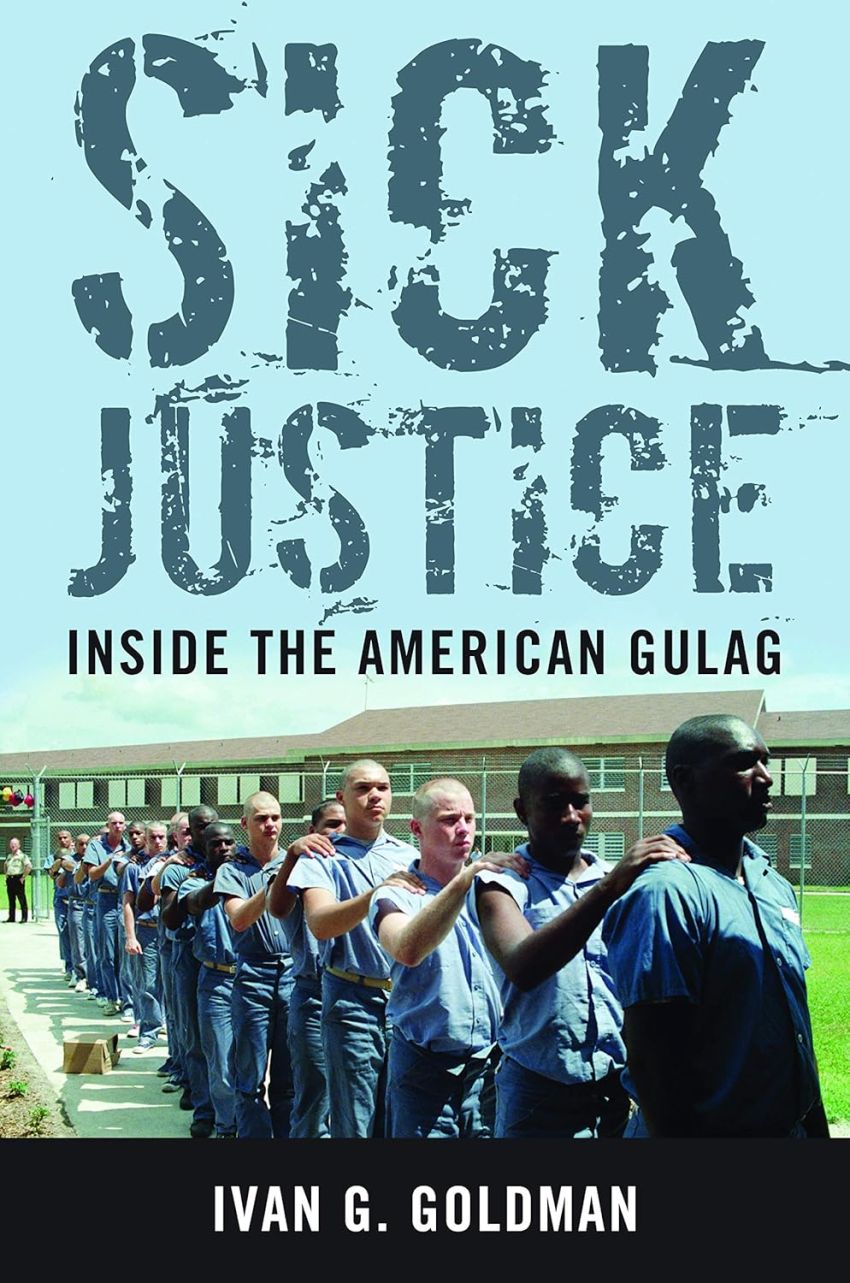

Sick Justice: Inside the American Gulag

By Ivan G Goldman

Potomac Books, 2013

256 pages, hardcover

Justice is criminally unjust in the United States. Its predatory bankers and warmongers rarely face charges, but the nation's prisons are packed with impoverished small-time crooks.

If the cells were a city, it would be the largest after New York, Los Angeles and Chicago: 2.3 million Americans live behind bars. One in every 100 adults is a convict, a rate that rivals North Korea.

These figures have shot up relentlessly since the War on Drugs began in the 1970s. This sustains a sprawling penal network that Sick Justice author Ivan Goldman compares to the Gulag, the Soviet agency that administered Stalin's work camps.

The US system might appear less brutal, Goldman argues in Sick Justice, but detaining the relatively harmless in vast numbers “can eventually transform a free but excessively punitive society into a totalitarian state”.

Giving addicts a prison term was not what the founding fathers had in mind. To quote the revolutionary writer Thomas Paine: “The law ought to impose no other penalties but such as are absolutely and evidently necessary.”

Instead, the courts keep locking people up, for longer stretches. Hardliners say harsh sentences cut crime, but experts contend that imprisonment makes things worse, by confining non-violent offenders with diehard sociopaths.

Those lucky enough to get out are branded lepers and are denied help from the state to turn their lives around. In Goldman's view, only “those who can convince themselves that gratuitous incarceration somehow benefits society might fail to view it as the atrocity that it is”.

Unfortunately, he laments, no amount of exposing these facts has an impact on policy. The reason for this is a “prison-industrial complex” of corporate interests, as insidious and destructive in influence as the arms trade.

“The Gulag industry,” Goldman writes, “can always justify putting more people in prison and imposing longer sentences, no matter what’s going on outside the walls: if crime rises, we must need more people behind bars. If crime goes down, wholesale imprisonment must be succeeding.”

These companies depend on human raw materials. In reports to investors, the largest US firm — the Corrections Corporation of America — warns: “Demand for our facilities and services could be adversely affected by the relaxation of enforcement efforts, leniency in conviction or parole standards and sentencing practices or through the decriminalization of certain activities that are currently proscribed by criminal laws.

“For instance, any changes with respect to drugs and controlled substances or illegal immigration could affect the number of persons arrested, convicted, and sentenced, thereby potentially reducing demand for correctional facilities to house them.”

Corporate prisons are still a minority, but they're chomping at an annual punishment budget of US$70 billion, assisted by a lobbying group called The American Legislative Exchange Council (ALEC). The group backs privatisation, mandatory sentencing and new ways of funnelling taxpayer cash to businesses, like providing ancillary services in jails or monitoring parolees.

ALEC even drafts “model” laws that get adopted.

Although northern and eastern states are still resistant, the most populous, California, seems converted. One California county now bills inmates for their food, so they wind up in debt to the suits that helped intern them. It is the standard outsourcing sales pitch: we'll do it cheaper by cutting more costs, and boost our profits in the process.

California is Goldman's home state. It has already led the way on stiffer sentencing, with a “three strikes” law that half the states have copied in some form.

To combat habitual crime, third-time offenders get locked up for decades. Like private prisons, this fad is spreading round the world. New Zealand passed similar laws in 2010.

The Californian rules were modified last year, restricting draconian jail terms to “serious” crimes. But those serving life for stealing socks or slices of pizza won't get pardoned.

The original law was sponsored by the prison guards union, which spends millions of dollars of members' dues on lobbying. For 30 years, it's “proved to Democrats and Republicans alike that building prisons and filling them with inmates can gain votes for politicians and simultaneously help their donors,” Goldman observes.

While funds for education were cut, the number of Californian jails has roughly trebled.

Reversing this trend is a Herculean task. Yet despite Goldman’s lively survey of what's wrong (from “zero tolerance” rhetoric to murky plea deals, suspect conviction rates and even official collusion in mass rape), some of his answers come off limp: “As long as we keep Quixotic, unjust laws on the books, harmless people will suffer.”

He sounds torn between writing for policy wonks and the public. “Democracy works best when the electorate understands the issues,” he says, suggesting more “accurate and substantial news coverage” can achieve this.

If only. It is 50 years since President Dwight Eisenhower warned voters about the military-industrial complex, which still hijacks trillions to fight phantom enemies, assisted by servile journalists and editors.

Although Goldman wants to end the conflict between criminal justice and the profit motive, he does not devote much space to explaining how. His most radical comments are sourced to a “left-leaning lawyer”, who says: “It's no coincidence that America's prison population exploded at the same time its distribution of wealth shifted sharply in favour of the richest.”

It therefore makes sense to see “mass incarceration as the ruling class's principal method of insuring against resistance and insurrection”.

Goldman appears to agree, having titled that chapter: “The War against the Poor (and Middle Class)”. If injustice is so well ingrained in the social order, why not structure the book as an argument for changing it? Anything less revolutionary seems doomed.

Sick Justice is an indictment of the system, but it ends on a strangely optimistic note: “Our republic, based on the inalienable principle of liberty and justice for all, has the courage and know-how to find better answers.” Here's hoping.

[Daniel Simpson is the author of A Rough Guide to the Dark Side, a memoir of why he resigned from the New York Times, about which he was interviewed by Green Left Weekly.]