-

As they are prone to do, the private media have invented a new thing. In both English and Spanish, they are calling it the colectivos. They are meant to be irrational, cruel, grotesque armed motorbike riders who “enforce” the revolution in Venezuela and are responsible for most of the violence afflicting the South American nation, which has left more than 30 people dead since February. The opposition barricaders are presented as the innocent victims of these collectivos, who apparently work with the National Guard and have the support of President Nicolas Maduro's government.

As they are prone to do, the private media have invented a new thing. In both English and Spanish, they are calling it the colectivos. They are meant to be irrational, cruel, grotesque armed motorbike riders who “enforce” the revolution in Venezuela and are responsible for most of the violence afflicting the South American nation, which has left more than 30 people dead since February. The opposition barricaders are presented as the innocent victims of these collectivos, who apparently work with the National Guard and have the support of President Nicolas Maduro's government. -

In a recent article, Amnesty International accused the Venezuelan government of a “witch hunt” when a right-wing opposition mayor Daniel Ceballos was arrested. However, Amnesty has yet to use such strong language against the five weeks of human rights violations people in Venezuela have suffered at the hands of violent opposition sectors. The “witch hunt” term demonises the people’s right to bring such criminals to justice.

In a recent article, Amnesty International accused the Venezuelan government of a “witch hunt” when a right-wing opposition mayor Daniel Ceballos was arrested. However, Amnesty has yet to use such strong language against the five weeks of human rights violations people in Venezuela have suffered at the hands of violent opposition sectors. The “witch hunt” term demonises the people’s right to bring such criminals to justice. -

Venezuela’s Mission Sucre has reached 10 years of providing higher education to more 695,000 people, including 379,000 who have already graduated. The government launched Mission Sucre in November 2003 to provide university education to those who previously didn’t have access to it. Many of its current students are people who have a low income and middle-aged mothers who weren’t able to continue their studies because they raised children.

Venezuela’s Mission Sucre has reached 10 years of providing higher education to more 695,000 people, including 379,000 who have already graduated. The government launched Mission Sucre in November 2003 to provide university education to those who previously didn’t have access to it. Many of its current students are people who have a low income and middle-aged mothers who weren’t able to continue their studies because they raised children. -

Representatives from 225 communes met over January 31 to February 1 in Barinas in western Venezuela to discuss strengthening the communal economy. Communes are made up of elected representatives from the communal councils, grassroots bodies that bring together local neighbourhoods. The conference was called and organised by the Bolivar and Zamora Revolutionary Current (CRBZ). The CRBZ is a current in the governing United Socialist Party of Venezuela (PSUV).

Representatives from 225 communes met over January 31 to February 1 in Barinas in western Venezuela to discuss strengthening the communal economy. Communes are made up of elected representatives from the communal councils, grassroots bodies that bring together local neighbourhoods. The conference was called and organised by the Bolivar and Zamora Revolutionary Current (CRBZ). The CRBZ is a current in the governing United Socialist Party of Venezuela (PSUV). -

Venezuelan President Nicolas Maduro criticised US “intervention” in the internal affairs of Latin American countries, and in the Honduran elections, on November 25. Xiomara Castro, candidate for the LIBRE party formed by the resistance movement that opposed the 2009 US-backed coup, declared victory after the vote. However, so did her conservative opponent, National Party's Juan Hernandez , with the Electoral Supreme Court (TSE) declaring Hernandez clearly ahead. LIBRE rejected the TSE's count, alleging serious fraud.

-

Venezuelan President Nicolas Maduro announced on September 10 that a Venezuelan Armed Forces plane would carry humanitarian aid to Syrian refugees in Beirut, Lebanon. The initiative came out of a resolution from the political council of the anti-imperialist bloc Bolivarian Alliance for the Peoples of Our America (ALBA) meeting in Caracas. The plane will bring blankets, medicine, and food. Established by Venezuela and Cuba in 2004 as an alternative to US domination, ALBA now involves eight nations from the region

-

Fearing state repression, farmers in the Cataumbo region of Colombia, on the border with Venezuela, have formally requested asylum in Venezuela. Farmers in the Rural Workers’ Association of Catatumbo (Ascamcat) erleased a public letter on June 21 asking Venezuelan President Nicolas Maduro for refuge. They have been protesting and blocking roads since June 10 in response to a campaign to forcefully eradicate coca cultivation in their area. They say they fear military reprisals.

Fearing state repression, farmers in the Cataumbo region of Colombia, on the border with Venezuela, have formally requested asylum in Venezuela. Farmers in the Rural Workers’ Association of Catatumbo (Ascamcat) erleased a public letter on June 21 asking Venezuelan President Nicolas Maduro for refuge. They have been protesting and blocking roads since June 10 in response to a campaign to forcefully eradicate coca cultivation in their area. They say they fear military reprisals. -

Founder of Venezuela’s world famous El Sistema music program, Jose Abreu, met with President Nicolas Maduro on May 22 to discuss expanding the program. They agreed on a project called Musical Program Simon Bolivar, which aims to have 1 million Venezuelan youths and children playing musical instruments.

-

There were large marches in Caracas by supporters and opponents of venezuela's revolutionary government on May 1, as well as smaller ones around the country, to mark International Workers Day. Government supporters celebrated a minimum wage rise and a new labour law that extends workers' rights. Government opponents, however, demanded a “fair wage”. President Nicolas Maduro marched with the pro-government march in Caracas, while opposition leader Henrique Capriles marched with his supporters in the eastern part of the capital.

There were large marches in Caracas by supporters and opponents of venezuela's revolutionary government on May 1, as well as smaller ones around the country, to mark International Workers Day. Government supporters celebrated a minimum wage rise and a new labour law that extends workers' rights. Government opponents, however, demanded a “fair wage”. President Nicolas Maduro marched with the pro-government march in Caracas, while opposition leader Henrique Capriles marched with his supporters in the eastern part of the capital. -

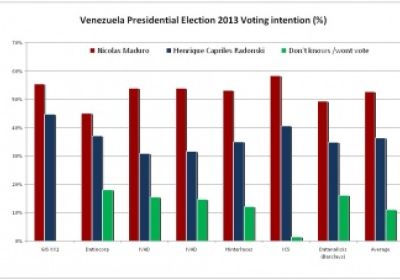

The results of Venezuela's presidential elections in a few weeks may well predictable, with polls showing socialist candidate Nicolas Maduro well ahead of his right-wing opponent. But we are going through a fragile, vulnerable period, with a future that is less predictable. These elections, as the start of the era of the Bolivarian revolution without its historic leader Hugo Chavez, have special characteristics and factors that go beyond the vote. Unity and leadership

The results of Venezuela's presidential elections in a few weeks may well predictable, with polls showing socialist candidate Nicolas Maduro well ahead of his right-wing opponent. But we are going through a fragile, vulnerable period, with a future that is less predictable. These elections, as the start of the era of the Bolivarian revolution without its historic leader Hugo Chavez, have special characteristics and factors that go beyond the vote. Unity and leadership -

Venezuela Analysis journalist Tamara Pearson's passionate and insightful report on the feeling among the Venezuelan people after the passing of President Hugo Chavez, the response of the opposition, the people's determination to continue their revolution, and the importance of international solidarity. Film by Green Left TV.

-

Vice-President Nicolas Maduro congratulated Ecuadorian President Rafael Correa for his “gigantic” victory in Ecuador’s presidential and parliamentary elections on February 17. Correa received 57% of the vote, achieving a strong lead ahead of the runner-up, banker Guillermo Lasso who got 24.06% of the vote. “We’re very happy, and we’ve communicated our congratulations from the whole people of Venezuela, from our president Hugo Chavez, to President Rafael Correa,” Maduro said.