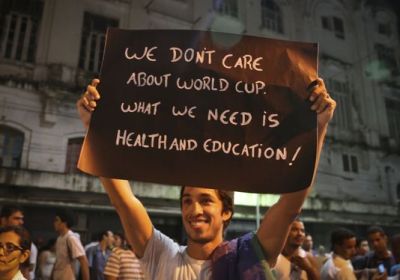

A fortnight out from Brazil’s October 5 national elections, the big news is the significant surge in support for Marina Silva, with some polls predicting the former Workers’ Party (PT) government minister and environmental activist could end up winning the presidential race.

Incumbent president and PT candidate Dilma Rousseff maintains a narrow lead over Silva, but the election will almost certainly go to a second round run-off on October 26.