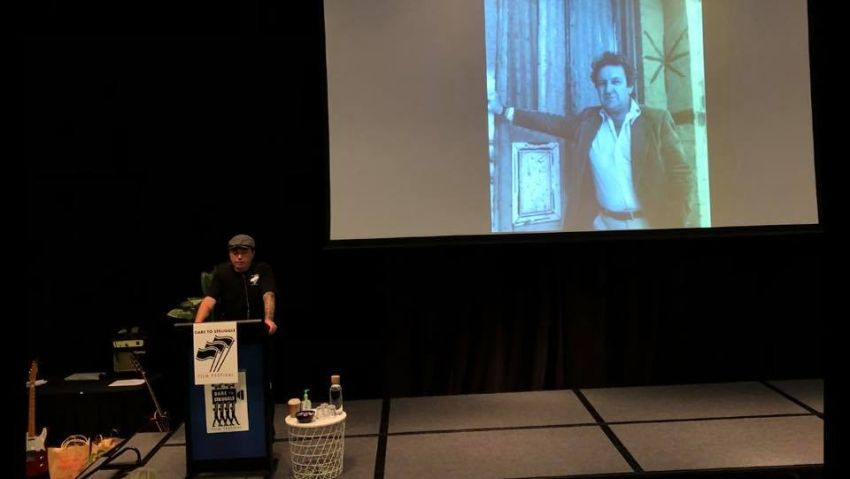

Judy Mundey is the patron of the Dare to Struggle Film Festival, which was launched at the NSW Teachers’ Federation on April 18 with a new film about Jack Mundey made by Jill Hickson and John Reynolds of Art Resistance. She gave the following presentation prior to the film's premiere.

* * *

The people behind the festival have been kind enough to say that Jack Mundey’s work has been the inspiration behind the project. The film we will see later shows something of Jack’s life and politics.

Jack first became publicly known because of the early struggles and innovative campaigning of the NSW Builder’s Labourers Federation to win better wages and conditions for the members of the union.

He had come from Far North Queensland to Sydney to play football and obtained paid employment as a builders’ labourer.

The work was notoriously lacking in safety measures, the amenities on site almost non-existent and the wages poor.

He joined the union only to discover that those who tried to do something about improving wages and conditions on the job were soon dismissed, not only with the support of the union leadership but often at their instigation.

He joined the rank-and-file organisation which, in an excellent example of daring to struggle, eventually overthrew the previous, corrupt, leadership of the union.

The newly-militant union’s campaigning for decent wages, amenities and safety on the job brought success, but could often be described as unconventional and certainly innovative.

Probably it was the use of the vigilante groups that brought most attention in those early days.

This was where building work constructed by scab labour, brought in by employers to defeat strike action, was demolished by the union vigilantes.

This brought howls of outraged protest and scathing attacks on the union in the mass media and from governments and employers. But, in one interview, shown in Pat Fiske’s 1985 film Rocking the Foundations, it was pointed out that 23 building workers had died on building sites that year and this, rather than the loss of some brick walls, was the real outrage.

The union’s campaigns were very successful: there was a huge growth in the union’s membership, the members developed pride in their union and had a new found self-respect.

These early struggles and the democratic practices of the union were vital to winning the support of the members when it later became involved in other campaigns, including support for Aboriginal land rights, for the rights of a gay student who had suffered discrimination and, in particular, for the Green Bans, which became internationally known and acclaimed.

In a 2016 article published in Links, John Tully described the NSW BLF as “the most radical and innovative union the world has ever seen”.

They were not always lauded. Quite the reverse.

There was a great deal of negative publicity — including sneering coverage about builder's labourers imposing bans to save buildings and places of historical, architectural, social or environmental importance as if builder's labourers could not appreciate history or beauty or nature.

But, thankfully, much of this wonderful history of the BLF has been recorded in Fiske’s marvelous and memorable Rocking the Foundations. Without such films, history is easily forgotten.

I don’t like to criticise the ABC. We need it more than ever. But a small example of this might be a recent ABC television series on home restorations. Two of the featured homes in the series were in the Rocks area of Sydney. The Rocks is Australia’s oldest white urban precinct and dates from the 1790s. It was home to a close knit working-class community, many living in the terrace homes that were a feature of the area.

In the 1970s the then state government planned to demolish the historical architecture and build high rise. This plan was defeated by a Green Ban, imposed at the request of the local resident action group.

There was no mention of this history, in either of the ABC programs. There was history about the whaling ship captain, who had owned one of the houses, but nothing about the Green Ban. Yet without that Green Ban, even if either of the terrace houses had survived, they would have been hugely overshadowed by high rise office towers, with the historical character of the area completely destroyed.

I doubt that either home would have then been purchased by their restorers, let alone been the subject of a home restoration program.

Fiske’s film reminds us vividly of that history of saving The Rocks.

In Sydney, we have become used to seeing a well-organised Mardi Gras parade through Sydney’s streets each year (COVID-19 aside) with large numbers of people taking part and large numbers of people to cheer them on.

But, in 1978, it wasn’t like that. There were no police taking part as a contingent in the march. They were there, but to disrupt, attack, arrest and bash those brave enough to take part and stand up for the rights of gay people.

But if those brave people had not organised, not dared to struggle, there would be no Mardi Gras as we know it. There would be no same-sex marriage legislation and there would still be ferocious oppression and discrimination.

A marvellous film Riot records the history of that struggle and the courageous role played by the pioneers.

The recent film Women of Steel records the struggle by women to win the right to work at the steel works in Wollongong and the award winning film, Radical Wollongong, is about the history of radical struggle by people in that working class area.

As the organisers of the Dare to Struggle Film Festival say: “These types of stories are poorly represented in main stream film festivals or the media because they clash with the interests of their corporate and government sponsors”.

The progressive political movement has a history of progressive cultural contributions, including film making.

The Waterside Workers Federation, the precursor of the Maritime Union, had a film unit in the 1950s. In just five years it produced 19 films on subjects that other film or newsreel producers did not tackle. For example, it produced a film truthfully portraying the pitiful living conditions in the slum areas of Paddington and Surry Hills.

That film was made to contribute to a broader campaign being organised by the Australian Council of Trade Unions and the Building Workers Industrial Union (the precursor to the current Construction, Forestry, Mining and Energy union) to try to obtain better living conditions.

The union leaders believed the creative arts, including film, were invaluable in putting forward an alternative picture to the mainstream media.

How much more important it is now to support independent film makers, with ever shrinking media diversity?

This issue has even spurred two recent prime ministers to speak out: Liberal Malcolm Turnbull, who gave evidence to a Senate inquiry earlier this month about Rupert Murdoch, and Labor’s Kevin Rudd. The Senate inquiry is being held because more than 500,000 people signed a petition organised by Rudd voicing concerns about the concentration of the media. We would agree, but might query why the issue was not addressed when they had some power to do so.

Such media concentration makes it less likely we will see stories of the struggles of ordinary people.

As for union film units, they largely no longer exist. Unions continue to struggle with falling membership and are always facing industrial “reforms” that would weaken them further. If the government had its way it would further de-unionise the workforce, possibly achieving something like the situation of the un-unionised Amazon workforce in the United States. They could certainly do with some progressive film-makers.

Meanwhile, here at home, we have widespread wage theft, irreparable environmental damage due to runaway climate change, ongoing species extinction, the disgraceful refugee situation, continuing damage to our river systems, the murderous situation in West Papua in our near north and Aboriginal people still dying in custody 30 years after the Royal Commission. Everyone here could point to issues that need coverage.

The Dare to Struggle Film Festival is being established to help focus on, tell the stories of, and document struggles for justice.

Today is its launch and the material distributed invites those who can to donate to help make the Festival a reality and to build on the fine traditions of progressive film making, helping to strengthen the social movements that are so urgently needed.

[Judy Mundey, a retired barrister, was elected as the first female president of the Communist Party of Australia in 1979. She was married to the late Jack Mundey. For more information, buy a copy of the film about Jack Mundey and to make a donation to help the film festival, visit www.daretostrugglefilmfestival.net.au.]