The temperature in the South Australian city of Port Augusta on January 30 peaked at 50°C — just 0.7°C short of the highest-ever recorded in this country.

Was this simply “weather” of the kind we’ve always enjoyed or suffered? Or was something much more dangerous at work?

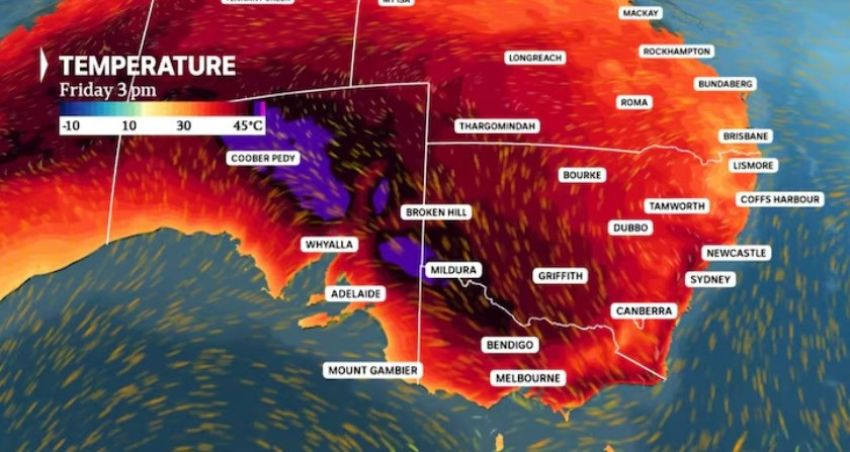

Port Augusta’s maximum that day marked the sweltering high point of two heatwaves that roasted Australia’s main settled regions last month. These events weren’t unprecedented — just the most extreme since 2019‒20.

But each had an intensity, geographical extent and duration experienced only a few times during the whole 20th century. So, is there some definite trend — and human factor — involved?

Professor Steve Turton, from Central Queensland University, explained the science in The Conversation on January 27. Each summer, Turton noted, monsoonal troughs over northern Australia push upper-atmosphere high pressure systems further south. Air from these systems then flows down over central, southern and eastern regions. As it descends, compression raises its temperature.

Nothing unusual there. But last month, the high pressure was further south than normal. And critically, blocking weather systems held it in place over the continent while temperatures built up. Still, that was nothing really out of the ordinary for an Australian summer.

But enter climate change. As analysed by the Commonwealth Scientific and Industrial Research Organisation (CSIRO), Australian land temperatures warmed on average by about 1.6°C between 1850‒1900 and 2011‒2020. “Very high monthly maximum temperatures that were recorded under 2% of the time in 1960‒1989 [occurred] 11% of the time in 2009‒2023”, a CSIRO report stated. “That is about 6 times as often.”

Consistent with this, World Weather Attribution (WWA) said of the first January heatwave, from January 5‒10: “We conclude that similar events are about 5 times more likely to occur now than they would have been in a preindustrial climate without human-caused warming.” What used to be once-in-25-year events, in short, could now be expected one year in five. As it happened, the next monster heatwave, considerably more severe, swept in only a few weeks later — from January 24‒30.

What will happen further down the track, if efforts to abate climate heating are not radically stepped up? Under current policies, the WWA site projected that heatwaves in Australia at the end of the century will be 1.5°C hotter still, and will occur one year in two.

Even for people who respond only to profit-and-loss calculations, the message here should be alarming.

Accompanying the first January heatwave, WWA reported, was “a surge in heat-related illnesses, with a 25% increase in emergencies in Melbourne”. When any prolonged, vigorous outdoor activity becomes dangerous, and heat stress causes accidents to multiply, the costs to labour productivity are obvious.

For the natural environment, the prospects include larger and more frequent bushfire catastrophes. During the previous round of extreme heat, in 2019‒20, as much as 21% of the continent’s forested area was recorded as burned.

Tackling climate disaster?

Enough, surely, to make certain that Australia’s rulers would take decisive action to end the country’s contribution to climate disaster?

It seems not.

One of the world’s leading energy analyst firms, Bloomberg NEF, concluded that Australia is unlikely to reach its current target for reducing the role of fossil fuels in meeting national electricity demand: “More needs to be done, and faster, for Australia to achieve its target for 82% renewable energy penetration by 2030”, the firm said recently.

The Queensland Liberal National Party (LNP) government’s determination to delay the closure of coal-fired power plants indefinitely is a key problem. This is despite reports that last summer, the state’s largely clapped-out coal generating units broke down, or were otherwise offline 78 times.

Meanwhile, modern renewables-plus-storage infrastructure in other states performed impressively during last month’s heatwaves.

In South Australia and Victoria, sky-high demand was met securely and reliably, while the role of rooftop solar meant that often, the cost of grid electricity stayed remarkably low.

The LNP government, which owns most of Queensland’s generating plants, is intent on wringing the last cent of revenue from its coal-fired clunkers — while continuing to line the pockets of its mine-owning mates.

But that does not mean the Labor Party is blameless on the climate change score. Last year, both the federal and Western Australian Labor governments agreed to extend the operating life of Woodside Energy’s North-West Shelf gas facility until 2070. As related by the Guardian, the extension will be responsible for carbon emissions of almost 90 million tonnes per year, or about 20% of Australia’s current annual carbon footprint.

Australian Conservation Foundation climate program manager Gavan McFadzean wrote in September that it “beggars belief that the Albanese government would choose to detonate this carbon bomb”.

Or, perhaps the choice is entirely believable.

Nothing in the recent history of the Labor Party suggests it will defy big-business interests when the latter have massive profits at stake — not even clear evidence of Australia’s climate turning apocalyptic and of the country’s environment being destroyed.

Under Labor, as under the conservatives, Australian capitalism is a greenhouse ogre that enriches itself by poisoning the world’s atmosphere.

As The Australia Institute reported recently: “Australia is the second largest fossil fuel exporter and fifth largest fossil fuel producer in the world. Emissions from Australia’s fossil fuel exports are … greater than the emissions of all countries except China, the United States, India and Russia. Australia is expanding fossil fuel exports with around 100 new fossil fuel projects under development.”

Granted, the effects of the coal and gas exports do not show up in Australia’s official emissions statistics. The future victims of bushfires and heat-stroke, though, will not take much comfort in that.

Meanwhile, the hyper-warmed atmosphere will blow back over Australia regardless.