Marx’s Theory of Value at the Frontiers: Classical Political Economics, Imperialism and Ecological Breakdown

By Güney Işıkara and Patrick Mokre

Routledge, 2025

Karl Marx’s economic theory is founded on the labour theory of value. In Marx’s Theory of Value at the Frontiers, Güney Işıkara and Patrick Mokre make a valuable contribution to Marxist economics, first, in demonstrating the empirical credibility of the labour theory of value and, second, in showing how it can explain the economics of imperialism and environmental degradation.

The labour theory of value — that the value of commodities which underlies their prices and, hence, regulates the capitalist economy, is determined by the amount of labour that goes into them — was a part of classical political economy prior to Marx. It was employed inconsistently by Adam Smith and then more thoroughly but anomalously by David Ricardo.

The anomalies of Ricardo’s theory were resolved by Marx, arguing that the value that can be produced by labour in, say, a day, exceeds the value of the commodity of a day’s labour power (based on the labour required for the worker’s continued survival) as purchased by a capitalist. The difference being a surplus value — the source of capitalist profits.

While Marx argued that value is the underlying basis for the formation of market prices, labour values don’t directly determine prices.

Value, price and profit

First, if similar products are produced by different companies more or less efficiently with, respectively, less or more labour, they can’t very easily charge higher price for products produced with more labour. Instead they tend toward a price based on the average labour required or “socially necessary labour”.

More efficient producers sell at the same price as the less efficient, so are more profitable. This, in effect, amounts to a transfer of a share of the overall value produced away from less efficient producers toward the more efficient.

Further than that, where different rates of profit result, particularly from the labour and technological composition of production in different industries producing different commodities, capital tends to move into those with higher profit rates, which then tends to level out profit rates to an average across industries and create an additional variance from values to prices.

Even things such as the sale or rent of untilled land or the loaning of money to companies can command a price due to the relative monopoly control over their ownership, even though they do not involve labour to produce and, hence, have no value.

Similarly, things such as administration, social work and weaponry do not produce value in spite of having a price. They may or may not have value in the ethical sense, but they do not produce economic value. Industries that are not productive of value command a price by effectively draining value from industries that are productive of value.

Once Marx used the labour theory of value to expose capitalism as a system based on exploitation, economics subsequently, in neoclassical form, reformed to base itself solely on market prices. Questions of underlying value were ruled out of bounds.

The question of value has been one of the most controversial issues in Marxist economics. It has been a focus of attacks from anti-Marxists but also a source of controversy within Marxism.

Making sense of mainstream economic data

Studying value empirically is a somewhat fraught process. This is in part due to theoretical differences within Marxist economics but also due to the fact that national and international organisations that produce economic figures are almost entirely committed to mainstream economics, for which value doesn’t even exist, only prices. For them, if a worker in Mexico is paid $20,000 a year while a worker in the United States is paid $80,000 a year producing the same good under the same conditions, that’s the respective value of their labour insofar as even there is such a thing.

To my knowledge, the only book-length treatment of the issue of producing meaningful information for Marxist economists out of the information given by the mainstream gatekeepers of economic information is Measuring the Wealth of Nations by Anwar Shaikh, one of the most important contemporary Marxist economists, and Ahmet Tonak.

As they write: “Conventional national accounts seriously distort basic economic aggregates because they classify military, bureaucratic, and financial activities as creation of new wealth.”

As former students of Shaikh, Güney Işıkara and Patrick Mokre are well placed to turn available economic data into meaningful empirical results.

They analyse three types of prices: (1) direct prices proportional to the socially necessary labour required to produce a commodity; (2) production prices which are the result of the process of the equalisation of the rate of profit between industries; and (3) observed market prices which, for Marx’s theory of value, can be expected to gravitate around production prices but are subject to conjectural ups and downs — the authors give the example of face masks and sanitisers during the COVID-19 pandemic.

The authors model values and prices based on the large multiregional input-output tables from the EXIOBASE project, which gives data for 159 industries and 44 countries over the 26 years 1995–2020.

Their results provide strong evidence for Marx’s theory of value. In 85 value-producing industries, the expected pattern of market prices gravitating around production prices was observed. In a further 35 industries, the pattern was more one of market prices converging towards production prices, while in 11 industries market prices did not show a strong connection to production prices.

Imperialism

Işıkara and Mokre then turn to look at what the empirical evidence shows in relation to Marxist theories of imperialism.

Imperialism as empire building through military expansion has existed for millennia. But imperialism as developed in the more narrow Marxist sense refers specifically to capitalism and the international economic relations, through which some countries are able to enhance their accumulation of capital through value transfers from other countries. Though this may involve military domination as with colonialism, it is fundamentally based on economic domination.

This has been the Marxist explanation of why countries separate fairly clearly into a rich Global North and poor Global South.

Marx himself pointed out that the transfer of value that takes place between more efficient companies and less efficient companies also takes place to countries that have more efficient production (roughly speaking more advanced technology) from those that don’t.

But Marx never got to write the planned volume of Capital dealing with the international economy. Theories of the mechanisms of imperialism were developed by subsequent theorists, notably Rudolf Hilferding, Nikolai Bukharin, Vladimir Lenin and Rosa Luxemburg, and further in the post-WWII period by theorists such as Arghiri Emmanuel and Samir Amin.

Theories of other mechanisms of imperialist value transfers from South to North were developed including the export of capital though loans or foreign direct investment and the repatriation of interest and profits to the North (or to tax havens); the use of value chains in production where the bulk of profits are realised up the chain in the North; and how companies in the North are able to use realise excess value by employing labour in the South and paying much lower rates.

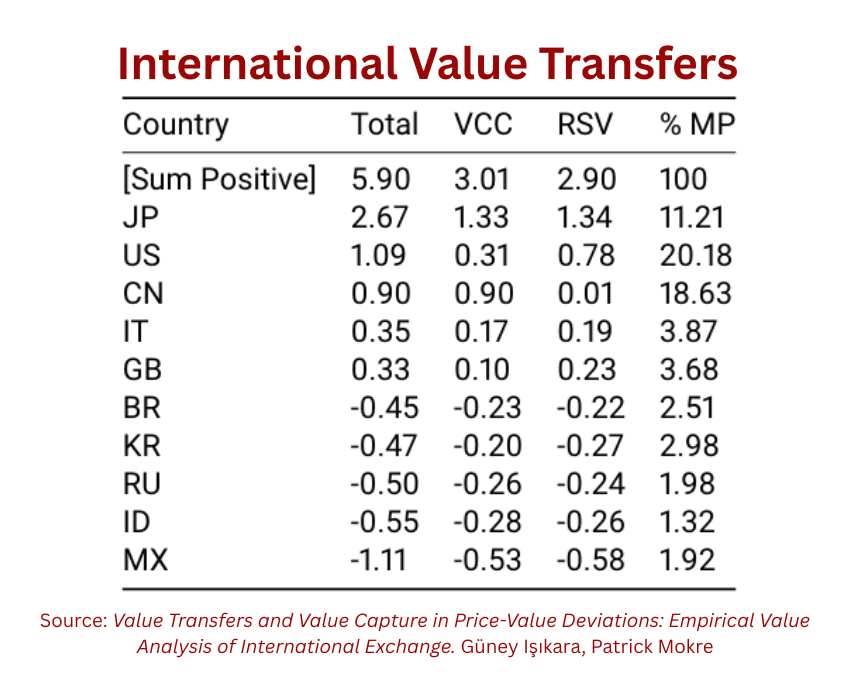

Işıkara and Mokre base their calculation of international value transfers on the differences between labour-equivalent direct prices and production prices (PP). They break this down into the components due to the value composition of capital (VCC) and the rate of surplus value (RSV) — roughly speaking that due to technological advantages and that due to the payment of low Global South wages respectively.

They found that in the 1995–2020 period studied, international value transfers corresponded to 5.9% of global output of value-producing industries and a total of €70 trillion. This breaks down into 3.01% due to VCC and 2.9% due to RSV.

Winners and losers

The five largest net positive transfers, in order, were to Japan, the US, China, Italy and Britain. The five largest negative transfers were from Mexico, Indonesia, Russia, South Korea and Brazil.

China, with a per capita income still a fraction of that of wealthy countries, emerging as a net winner is surprising. It would have certainly gained in recent years by offshoring production to still-poorer countries and through foreign loans and investments, but it still also plays the role in the global economy of the world’s low-wage workshop. The data shows it started the period studied as a net loser but moved into the positive around 2005–10.

This lends credibility to the argument that some make that China is, or is becoming, an imperialist nation. I would caution that while imperialism is founded on an economic basis, it shouldn’t be reduced to its economic basis — as something that emerges on the day international value transfers click over from negative to positive.

Another interesting result is finding Russia among the largest net losers. Following its invasion of Ukraine, it has been debated that it should be classified as an imperialist country. The results lend evidence to the argument that it might be imperialist in the millennia-old sense but not in the specifically Marxist economic sense.

The book also gives separate data for what the authors call “value capture” as opposed to “value transfer”. By this, they mean international value flows from value-producing to non-value-producing industries. Falling under this category are profits, interest and fees due to capital exports, finance and insurance.

Here, the authors say that their figures are probably underestimates due to the difficulty of extracting relevant data but their results find that such value capture is only about a twentieth the significance of the value flows under the heading of value transfers.

Nature and capitalism

Işıkara and Mokre also look at value in its role in the relationship between human and non-human nature. Non-human nature is used in capitalism for agriculture, forestry, mining, hydroelectricity, etc.

As noted, untilled land does not incorporate labour and so has no value. Though Işıkara and Mokre point out that this sense of value is not to be confused with ethical value — as some ecological critics of Marx have done.

It is also important to note that value here is also different to what Marx called use value — the value of something simply as a useful object. Commodities have value in both senses but it is through their value in the former sense that they play a role in regulating the capitalist economy and capital accumulation not through their use value.

In spite of not having value, non-human nature plays a vital role in the capitalist system of value distribution through the formation of rents. As a monopolised means and condition of production, land can still command a price, capturing some of the value created by value-productive industries.

Işıkara and Mokre discuss the theoretical aspects of land rent and analyse its role in value distribution in a similar manner to their analysis of international value transfers.

They point to the way in which the incorporation of non-human nature into capitalism leads to its degradation:

“The labour process, a transhistorical metabolic interaction between humanity and nonhuman nature that produces values, takes the form of value under capitalism; and value creation is not achieved for its own sake but for the sake of valorization and accumulation. Although value is a purely social process, it is made possible by and operates on the basis of not only wage labour but a ceaseless process of expropriation and appropriation.”

Under capitalism, humanity can destroy nature even to its own detriment as its use values — as land to supply food or non-renewable minerals — are a necessary basis for capitalism, but it is only though their role in economic value that they enter into the logic of capitalist value creation and accumulation. Their use values don’t count.