The Labor-controlled Inner West Council pushed through a developer-friendly, high-rise housing plan, despite significant community opposition, at its September 30 meeting. Seven out of 15 councillors voted against.

The plan provides for just 3% of “affordable” housing, and would degrade the living environment.

The Better Future Coalition, a hastily formed coalition of community groups, is opposing the plan, insisting instead on public housing, green spaces and social infrastructure, rather than evictions of current residents and bonuses for private developers.

Council’s so-called Our Fairer Future Plan, which aims to demolish whole neighbourhoods for high-rise apartment towers in Marrickville, Dulwich Hill, Ashfield and Leichhardt, set the stage for this fight, which involves members of the Greens, Socialist Alliance, NSW Socialists and even Labor.

The push for the massive densification in the Inner West comes from the developer lobby — Urban Taskforce and the Property Council — in league with federal and NSW Labor elites and local planning bureaucrats.

For example, Tom Forrest, CEO of Urban Taskforce, the main developer lobby group, was chief-of-staff for former Labor premier Morris Iemma. With parentage like that, who would expect decent urban planning?

This matrix justified what they called Transport Oriented Development (TOD) by its proximity to rail and Metro stations. This key justification for more development has never been really questioned by the mainstream media.

“(Un)Fairer Future”, as critics have dubbed the council’s plan, is an attempt by the IWC to “improve” on the TOD plan. Instead of a six-storey limit, the plan proposes heights up to 17 storeys and high-rise development way beyond TOD’s 400-metre radius from rail stations.

Instead of the 17,000 additional dwellings proposed under NSW Labor’s TOD plan for the Inner West, the council’s plan proposes 31,000. (A joint IWC-government announcement a fortnight ago promised another 8000 dwellings under the guise of “rejuvenating” Parramatta Road.)

The plan contains no new parks, playing fields, urban bush or provisions for more schools, preschools and medical facilities, despite the 70,000 new residents it aims to introduce. It is not as though there is enough green open space now — residents in the Inner West enjoy the second-lowest amount of open space per capita in the state. Even the IWC acknowledges the acute shortage of playing fields.

Development on the proposed scale would lead to a net loss of green open space in neighbourhoods where backyard gardens and trees were razed to make way for excavations for footings and underground car parking.

As for basic infrastructure, Sydney Water has warned that this level of new development would soon overwhelm its wastewater capacity. Hawthorne Canal, which runs along the western edge of Leichhardt, the suburb slated for most redevelopment, already has signs every 50 metres warning of sewage overflow.

Essentially, the IWC plan offers current and future residents expensive housing in impoverished or degraded living environments.

Developer bonuses

The (Un)Fairer Future plan is laden with bonuses for developers.

The plan itself gives the example of a building in a 10-storey zone that can go to 17 storeys with bonuses. On the other hand, the “affordable housing” contribution has been set at 2%, rising to 3% after four years.

“Affordable” is defined as 80% of market rent, which is itself unaffordable for many wage-earners.

The IWC has sought to justify this risible level of dubious affordable housing by pointing to an economic feasibility study it commissioned. It concluded that developers would not build if the levy was set at anything above 2%. If the allowable heights were trebled, then they could possibly lift their contribution.

All this study did was to prove the bleeding obvious: that relying on private developers to provide decent, affordable housing is a chimera.

The near absence of affordable housing provision, let alone any quality public housing, has been a lightning rod for opposition, including in the Labor party itself.

Groups like Labor Against Homelessness spoke out publicly against the plan at a recent (tightly controlled) council-run public forum on the plan.

In an attempt to fend off criticism, Labor mayor and Anthony Albanese protégé Darcy Byrne said council is offering four of its carparks to community housing providers and private developers for affordable housing. But that will only yield a maximum of 341 dwellings, according to council’s own reports.

The plan also contains inducements for churches to develop housing, including affordable housing, by exempting their projects from height and floor space limits and waiving contributions for infrastructure.

In a late amendment, council now wants neighbouring private developers to share these exemptions.

While these ploys may add a little more dubious “affordable” housing, other projects could reduce current affordable housing. Critics in the Better Future Coalition point to the probability that the first housing to be demolished for this redevelopment is likely to include existing lower-range rentals, as their landlords could be easier to persuade to sell than individual homeowners.

This points to a key weakness in the plan: its reliance on developers buying up groups of houses and amalgamating them into a lot large enough to accommodate a 12- or 15-storey development.

An economic feasibility study accompanying (Un)Fairer Future estimated that less than 30% of the projected 31,000 dwellings would be built because of the costs and difficulties of amalgamating lots.

Byrne has sought to overcome this hurdle by touting a financial bonanza to anyone who sells to developers.

“If your home was worth $2.5 million,” Byrne told the August 19 council meeting, “you could now sell it to a developer for $3.5 million”. There are the anecdotes from residents in some upzoned streets who did sign on to sell sometime in the future — but who are already regretting it.

Trickle down housing?

The IWC plan does have its supporters, including many journalists who pump out the claims of developer lobbyists, Labor ministers, planning bureaucrats and local councillors.

The YIMBY acolytes are also active, although in public gatherings they garner little to no support. They parrot the trickle-down economics and simplistic supply-side arguments that more private development is the solution to the housing availability and affordability crises.

But that is disproved by evidence. There has been no increase in affordability in areas that have recently been developed for high-rise, or medium-rise, housing that the YIMBYs advocate. In fact, the opposite is the case.

A NSW parliamentary research paper on housing economics last August by two economics professors exploded the YIMBY claims. Using only peer-reviewed research, Rachel Ong ViforJ and Chris Leishman found the evidence for trickle-down or “filtering” — the idea that richer people buying new properties meant the leftovers were cheaper and more available for the rest of us — to be “limited and relatively weak”.

The community has not swallowed the pro-developer Kool Aid. The IWC’s efforts to inform residents were more sales pitch than anything else, yet the plan elicited over 3000, mostly oppositional, responses when put on public exhibition in June.

As the refreshingly frank report from the community engagement consultants pointed out, residents are concerned with the obvious drawbacks of the plan — its failures to provide affordable housing, decent communal amenity and liveable neighbourhoods.

“There was a clear desire for more affordable housing, open space and social infrastructure,” their report said. Elsewhere it noted “strong emphasis on the importance of investment in social infrastructure — such as schools, health services and open space — before densification occurs”.

Five times as many respondents supported reducing building heights and density compared with those who wanted to go higher and bulkier.

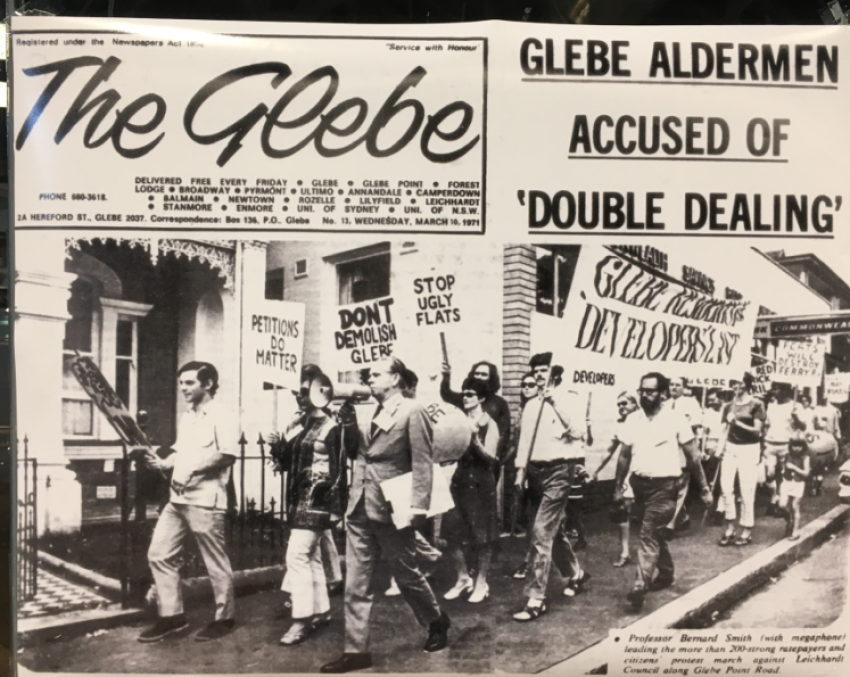

Nick Origlass, Issy Wyner, Jack Mundey, Ted Mack and the women of Kelly’s Bush would have been delighted by the extent and content of the responses. It provides the basis for democratic planning, for a community-directed rather than developer-led plan for the Inner West.

Such an approach, based on public participation, would result in a plan that emphasised quality public housing, green open space and the social infrastructure that should accompany any development. It would respect existing neighbourhood communities and embody a deep appreciation of the demands of the climate emergency. These fundamentals are largely lacking in the current (Un)Fairer Future plan.

[Hall Greenland is active in the Better Future Coalition. This article was updated on September 30.]