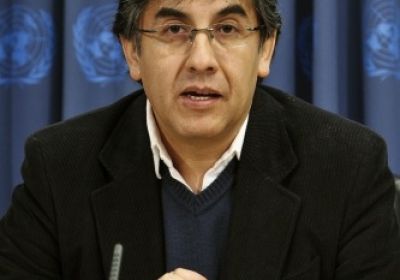

Alina Canaviri Sullcani is a Bolivian indigenous peasant now visiting Australia. Canaviri is active in Santa Cruz as a leader of the National Federation of Indigenous Peasant Women of Bolivia “Bartolina Sisa” and the Movement Towards Socialism (MAS) party led by President Evo Morales.

Canaviri spoke at the Latin America solidarity conference in Melbourne over October 8-9 and will be a featured guest at the solidarity conference held in Sydney over October 16 and 17 (visit www.latinamericasolidarity.org for details).