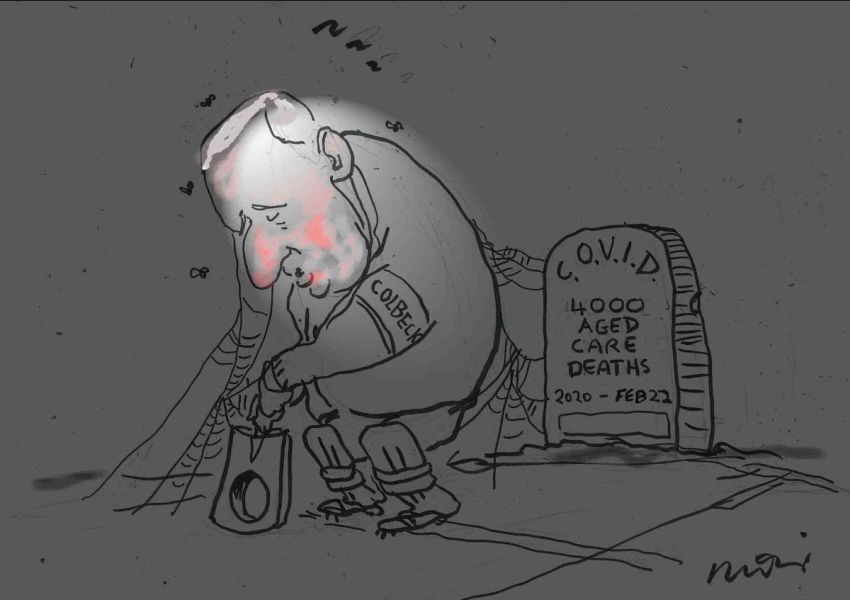

Aged residents in care are dying at alarming rates from COVID-19 while Prime Minister Scott Morrison and federal Minister for Aged Care Richard Colbeck waste precious time trying to convince us that the system is not in crisis.

Most of the 1500 deaths from COVID-19 in residential aged care were preventable. Omicron has made it worse; in just the past six weeks, 550 people have died from the virus.

The federal government has ignored the warnings of the Royal Commission into Aged Care Quality and Safety that found “substandard care” and abuse are routine and that infection prevention and control was poor.

Despite the crisis, none of the commission’s recommendations have been implemented.

The 15 COVID-19 deaths at Jeta Gardens Aged Care Facility in Queensland in January mirrors the deaths of 45 residents at St Basil’s Nursing Home in Victoria last year.

The Aged Care Quality and Safety Commission (ACQSC) said residents at Jeta Gardens are at an “immediate and severe risk”. But the Queensland Health Department said residents did not need to be evacuated: 100 residents and 82 staff have contracted the virus and are bracing themselves for further casualties.

The aged population’s mortality statistics from the pandemic are shocking enough. However, they do not take into account the pain and suffering experienced by the person’s loved ones after they die.

The federal government’s refusal to act shows how little value it places on the lives of the vulnerable aged community. “There are no simple answers,” the PM smirked while offering band-aid solutions and ill-thought-out policies such as a paltry $800 for aged-care workers.

This will not solve a problem that long predates the pandemic: age care workers are underpaid and have to work in poor conditions in privatised workplaces. No wonder they are leaving in droves. Many, too, have also succumbed to the virus.

Morrison’s latest brain snap involves sending 1700 Australian Defence Force troops to help out. It is more than a little ironic that he has to resort to deploying public servants to rescue the private aged-care sector, which, despite enormous government hand-outs, has run its own workforce into the ground.

Federal and state governments were slow to help this vulnerable sector from the beginning. Aged-care workers had limited access to personal protective equipment and large numbers of staff were furloughed and often not replaced by similarly experienced workers or by anyone.

This meant that some residents were left to die from neglect, or were inhumanely isolated for long periods. Their mental health suffered as families were banned from visiting and they had minimal access to allied health specialists.

The vaccination roll-out has also been very slow: as at early February, 61,000 aged-care residents were still waiting for their boosters and rapid antigen tests are in short supply.

After years of deregulation, privatisation and the rorting of government hand-outs, the aged-care sector was in such a weak position it could not respond effectively to a crisis such as a pandemic.

The Australian Nursing and Midwifery Federation (ANMF) has been pushing for reforms for years, but this has fallen on deaf ears.

The deregulation of the aged care sector began after the introduction of the Aged Care Act 1997, which removed mandatory staffing levels, opened the door to privatisation and fostered the reliance on an underpaid, increasingly unqualified and casual workforce.

Many aged-care workers are forced to work at multiple sites to scrape together a living wage. In the context of COVID-19, this means risking their own health and safety and, also, spreading the virus.

Private aged-care providers engage in exploitative practices. Low paid, casual migrant workers are hired so the bosses can maximise their profit margins.

This directly links to the poor treatment and care received by aged-care residents. Employing workers on a permanent basis and ensuring full industrial, residency and citizenship rights to all migrant workers is key to providing better care.

The ANMF has launched a campaign for “four key actions to fix aged care”. Its demands are for: at least one registered nurse on site at all times; greater transparency – funding tied to care; minimum mandated care hours; and better wages and conditions.

The Health Services Union in Victoria launched a campaign for a 25% wage rise for aged care workers in November 2020. The Fair Work Commission has said a decision will not be made until July — after the federal election.

The Socialist Alliance is campaigning for an end to the privatisation of aged care, and says the sector should be brought back under public administration for greater transparency and control. We need to ensure that public funds to the sector are made accountable and that the rorting by private companies is stopped.

We want to see an immediate wage rise and an end to the casualisation of the aged-care work force.

The COVID-19 crisis has shown up the fault-lines, including in rich Australia. Aged care left to the market has well and truly failed to provide quality, humane care. Vulnerable populations, and their carers, need and deserve better.

[Jackie Kriz is an experienced registered nurse, a committed unionist and has worked in the aged care and mental health sectors for decades. She is a member of Socialist Alliance.]