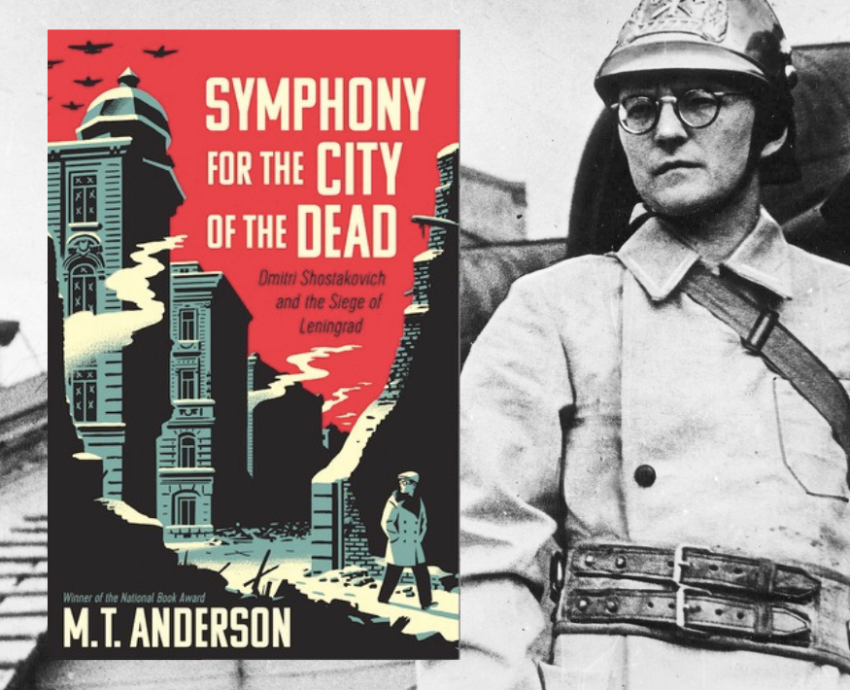

Symphony for the City of the Dead:

Dmitri Shostakovich and the Siege of Leningrad

By M T Anderson

Candlewick Press, 2017

464 pp., $23.95

The statistics themselves are shocking. In WWII, of the casualties borne by Britain, the United States and the Soviet Union, 95% were borne by the Soviets and 90% of the Germans killed by the three Allied powers were killed by Soviet forces.

In the Soviet Union, 32,000 factories were destroyed, as were more than 40,000 hospitals, 84,000 schools and 43,000 libraries.

Hitler launched his attack on the Soviet Union on June 21 1941, and within a short space of time, German fascist forces had encircled the key city of Leningrad, cradle of the Bolshevik-led revolution of 1917. The country was woefully underprepared to defend itself.

Under the pressure of international isolation and Russia’s backwardness, and after a cruel civil war in which the young country was invaded by a conglomerate of imperialist armies, the 1917 revolution had degenerated into a bureaucratic dictatorship headed by Josef Stalin and the bureaucratic clique around him.

By the late 1930s, Stalin had executed the vast majority of the old Bolsheviks who had stood shoulder to shoulder with Lenin and Trotsky in 1917, and had also purged the Red Army of tens of thousands of its officers and finest military minds. Little wonder, then, that initially the fascist forces swept across the Soviet Union, so quickly that Hitler arrogantly issued an order that Leningrad should be wiped from the face of the earth.

With the city surrounded and the main food depot destroyed in a bombing raid, the fascists decided to literally starve the city to death. Leningrad’s citizens were reduced to eating bread made from sawdust, soup made from wallpaper glue, and in the darkest days of the siege, some were reduced to cannibalism.

Caught up in the maelstrom was the young Soviet composer, Dmitri Shostakovich. Shostakovich had composed his first works in the early days of the revolution, but had only narrowly escaped being purged when Stalin took exception to his powerful opera Lady Macbeth of the Mtsensk District.

At the outset of the siege, Shostakovich found himself trapped in Leningrad, and between stints on duty as a fireman disabling incendiary bombs, had begun to compose what was to become his Seventh Symphony. In fact, he completed three of the eventual four movements in the besieged city, before he was flown out by the Soviet government to the relative safety of Kuibyshev, behind the Ural Mountains.

After Shostakovich finished the symphony, the Soviets formed the audacious plan of performing the symphony in Leningrad itself (which was still under siege). The only orchestra that had remained in the city was the Leningrad Radio Orchestra, but it had stopped performing, and those of its players who weren’t already dead were literally dying of starvation.

At the first rehearsal, there were only 15 players, some of whom were too weak even to hold their instruments. Three orchestral musicians died before the actual performance. Bolstered by musicians from the military, some of whom would come to rehearsals directly from the front line, the symphony was eventually performed on August 9, 1942.

Remarkably, the Soviets set up loudspeakers so that the Germans, dug-in on the outskirts of the city, would hear it. In addition to raising the morale of the Leningraders who heard it, it affected the morale of the Germans.

One year later a German soldier told Karl Eliasberg, the conductor of the first performance: “It had a slow but powerful effect on us. The realisation began to dawn that we would never take Leningrad. But something else started to happen. We began to see that there was something stronger than starvation, fear and death — the will to stay human”.

There has been much academic controversy about Shostakovich in recent decades, following his death in 1975. Was he, as the Soviets claimed, loyal to the regime, or was he (as Solomon Volkov claimed in the alleged memoir he published in 1979) a secret dissident?

In this book, Anderson takes a measured and sensible approach: Shostakovich was neither a loyal Stalinist nor a scornful dissident, just a composer with no special fondness for the capitalist west trying to keep himself and his family alive in an extreme period of human history.

Although this book is ostensibly written for a “young adult” audience, it is so well-written — and so well-presented and illustrated — that adult readers will find it engrossing. Overall, it provides a vivid portrait of how music can enable people to stay human in the face of fascist tyranny.