The legacies of colonial rule and capitalism’s expansion created deep economic inequality in Bangladesh. Its history has been marked by people’s resistance against colonialism and national liberation struggles.

The borders of Bangladesh were established with the division of Bengal during the partition of India and Pakistan in August, 1947. Bengal was divided as East Bengal — as part of the newly formed Pakistan — marking the end of British colonial rule in the land.

The resistance of Bengal (today’s Bangladesh) against British colonial rule is often ignored and overlooked in mainstream history. The famous proverb during the British era, “What Bengal thinks today, the whole of India thinks it tomorrow”, shows the socio-political awareness of the Bengali people.

Bengal was split along religious lines — Muslim-majority regions became part of Pakistan and other regions part of India. The name East Bengal officially changed to East Pakistan in 1955.

East Pakistan (Bangladesh) was part of Pakistan from 1947–71. Although there is a misconception that it was a fight between India and Pakistan, Operation Searchlight on March 25, 1971, was the leading cause and start of the genocide against the people of East Pakistan by the Pakistani military. This led to the Mukti Bahini — the Bangladesh freedom fighters — declaring independence, and the start of the Bangladesh Liberation War.

Ordinary people, such as students, teachers and farmers, took part in the liberation war and were trained in India. More than 3 million people were killed and 200,000 women were raped and tortured during the liberation period.

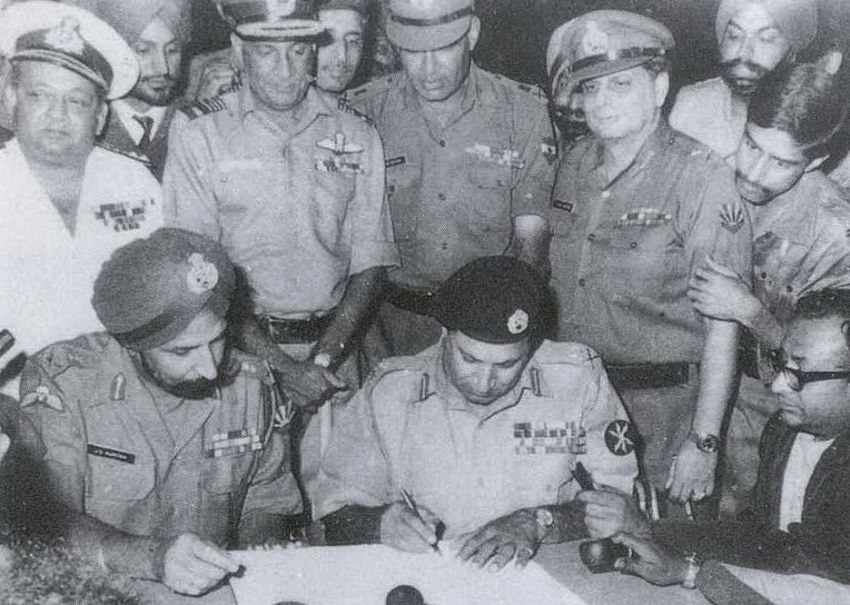

The Indian military joined the war on December 3, 1971, after Pakistan launched pre-emptive airstrikes on North India. Facing a war on two fronts and the rapid advance of the Mukti Bahini and Indian military, Pakistan surrendered in Dhaka — the capital of Bangladesh — on December 16, 1971.

Independence

The Awami League, a leading political party, formed government after independence and enshrined secularism in the constitution in 1972. The Awami League government imposed a one-party system in 1975, creating political dissatisfaction.

Members of the military killed President Sheikh Mujibur Rahman and most of his family members on August 15, 1975. This led to politically instability, as multiple military coups and counter-coups followed.

General Ziaur Rahman assumed de facto power as Chief Martial Law Administrator in 1976 and took over the presidency in 1977. He removed secularism from the constitution, which has never been reincorporated.

The political situation was still unstable, evidenced by General Hussain Ershad declaring himself Chief Martial Law Administrator, after Rahman was assassinated. However, in 1986, Ershad lifted martial law and reinstated the constitution. Following that, Bangladesh experienced the first widely accepted national election in 1991. The Bangladesh Nationalist Party (BNP) won the election — the start of democratic Bangladesh.

The BNP won the elections again in 2001. Military forces once again tried to take power in 2006. The army-backed unelected government only lasted two years, because of substantial public dissatisfaction, protests and international pressure.

The Awami League won the 2008 elections with more than two-thirds majority in the national parliament, which gave them ultimate power to amend the constitution. They are still in power by questionable means.

Due to political instability, Bangladesh never successfully created an effective bureaucratic system. Instead, it adopted the bureaucratic legacy filled with corruption left by British colonial rulers. After initial years of political turmoil, capitalism became the guiding principle in government policies, which created socioeconomic inequality. This can be seen in Dhaka.

About 9 million people live in Dhaka. There is a common proverb — “Dhaka never sleeps”. Dhaka has modern homes, technologies, good education, medical services, businesses and jobs. However, these modern facilities do not make Dhaka attractive — it is one of the world’s most populated and least liveable cities, due to noise, air and water pollution. More than two million people live without any proper shelter. The rich are getting richer by stretching their economic and political powers, often immorally and criminally, while the poor remain poor.

Climate change

Along with political and capitalist disadvantages, Bangladesh is a naturally disaster-prone country, due to its geography. It has been affected by more than 200 natural disasters in the past three decades. Storms are the most frequent disaster, followed by floods, epidemics, earthquakes, droughts and landslides.

Bangladesh is one of the countries most at risk from climate change’s negative impacts, such as extreme weather events, soil salinisation, rising sea levels and riverbank erosion. Natural disasters severely hit the poorest, most marginalised and vulnerable communities repeatedly exposed to hazards without the means to recover.

The expansion of capitalism, through globalisation and imperialism, has caused social exclusion, poverty and environmental degradation. A legacy of capitalism is the rise in Islamic fundamentalist forces that have created an extremely critical situation in the country, which now seems poised on the edge of a civil war between two concepts.

One concept recognises the common Bengali identity for all people, irrespective of their religion. The other concept visualises Bangladesh as an Islamic country. Islamic fundamentalists believe those who are not Muslims should be treated unequally, and those who consider themselves Muslims must be conservative and fundamentalist — which is against Bengali culture.

Both forces were active before Bangladesh was born, during its existence as East Pakistan. As Bengali nationalism grew in strength and ultimately overthrew the colonial rule of East Pakistan to emerge as an independent Bangladesh, the forces that wanted a religious identity remained.