Little more than 10 years after the Global Financial Crisis, the world economy faces another crash. Last time, the trigger was so-called “sub-prime” mortgages; but this time, it is a virulent virus — COVID-19 — writes Graham Matthews.

Little more than 10 years after the Global Financial Crisis, the world economy faces another crash. Last time, the trigger was so-called “sub-prime” mortgages; but this time, it is a virulent virus — COVID-19 — writes Graham Matthews.

The sheer scale of the recent bushfires and their timing (during the summer school holidays) have had a crippling impact on many working people, including small business owners, and put the ongoing sustainability of rural communities at serious risk, writes Graham Matthews.

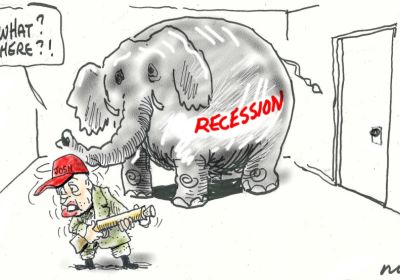

Treasury says the economy is performing “modestly”, Treasurer Josh Frydenberg has dismissed calls for additional stimulus spending & Reserve Bank of Australia chief Philip Lowe predicts growth will return to “trend” over the next year.

So nothing to worry about, right?

National accounts figures released by the Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS) on September 4 show economic growth was slower over the 2018–19 financial year than at any time in the past 10 years.

"As a result of the cultural-left’s long march through the institutions … political correctness involving identity politics, privileging victimhood and virtue signalling dominate public policy and debate", whined Kevin Donnelly, Senior Research Fellow at the Australian Catholic University, in the Sydney Morning Herald.

"Like never before Free Speech is facing extinction in Australia", exclaimed conservative activist group Advance Australia. "We are at a crossroad. We either stand up and demand a fair go or we get trampled."

Yet is it really the free speech of conservatives, right-wing radicals and religious fundamentalists that is under attack?

The economic slow down means the Coalition will either abandon its promise of increasing budget surpluses and increase government spending — on infrastructure for instance — to stimulate the economy or it will double down on its commitment to a surplus, necessitating spending cuts. Its track record suggests the latter, writes Graham Mathews.

Minister for Families and Social Services Paul Fletcher announced on September 26 that the National Disability Insurance Scheme (NDIS) had reached the milestone of registering its 200,000th participant. That same day, the Sydney Morning Herald reported that the final figures for the 2017-18 federal budget showed the budget deficit had been reduced to $10.1 billion, with "the single biggest saving [being] the lower than expected numbers of participants entering the NDIS.”