In the rush to heap scorn upon the Donald Trump administration, the president’s critics sometimes miss the forest for the trees. Such was the case in June when Donald Trump announced the creation of the so called Space Force, a sixth branch of the US military.

Critics mocked the idea as “ridiculous”, “stupid” and part of an “imaginary space war”.

“There’s no threat in space! Who are we fighting?” asked Stephen Colbert. Vox wondered if the Space Force would carry lightsabers.

It was easy to miss that the idea is not uniquely Trumpian—and poses a real threat. For all intents and purposes, a space force already exists in the form of the Air Force Space Command (AFSPC), a 36,000-person division of the Air Force that’s been operating since 1982.

Where Trump’s proposal differs is that it forms an entirely new military branch devoted to space, something James Clay Moltz, associate professor at the Naval Postgraduate School and author of The Politics of Space, says is “largely unprecedented”.

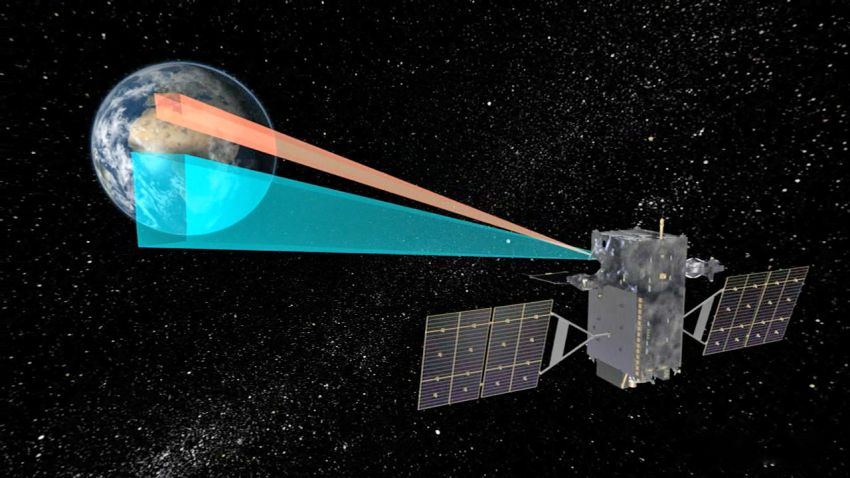

According to Vice President Mike Pence, the Space Force would include a new centralised command structure for space operations that would take over satellite-based military tasks such as surveillance and navigation for ground troops, as well as monitoring and tracking missile launches. These tasks are all currently performed by the AFSPC.

It’ll also take charge of any offensive capabilities developed for space, such as anti-satellite weapons (ASATs), introduce an “elite group of joint war-fighters” to support the rest of the armed forces, and oversee a new agency dedicated to developing “cutting-edge warfighting capabilities” for space.

The proposal is viewed by the space savvy in the military as “either unwise, unnecessary or premature”, Moltz says — and almost certainly expensive. It’s on the basis of its potential wastefulness and redundancy that critics such as Defense Secretary James Mattis, ex-astronauts Mark and Scott Kelly, Air Force secretary Heather Wilson and other members of the military have assailed the idea.

But there’s a much bigger debate to be had. International conflict in space is no longer a plotline ripped from a sci-fi paperback. A space war is becoming more and more likely.

Space geopolitics

US military dominance in space is really about maintaining military dominance on Earth. Space infrastructure, particularly satellites, is key to the US military’s global reach, servicing everything from navigation to weapons targeting to communications.

The global space arms race began with the Cold War, when both the US and USSR began testing ground-based anti-satellite (ASAT) weapons. During Ronald Reagan’s administration, the US Air Force became the first to test one on a spacecraft, destroying an old observation satellite in 1985.

The 1990 Gulf War — known now as the first “space war” — made US empire and satellites inseparable. With 24-hour satellite support, US forces could not only communicate across broad channels, but map out terrain, observe and predict enemy actions, and use new guided, “smart” weapons that were, in theory, less indiscriminate. Satellites make today’s drone warfare possible.

The US and Russia have adhered to what Laura Grego, senior scientist in the Global Security Program of the Union of Concerned Scientists, calls an “unofficial moratorium” on stationing dedicated weapons in space (as opposed to ground-based systems that target spacecraft). However, the US — and, increasingly, its rivals — continue to invest in other forms of space militarisation.

The US leads the way in satellite capacity and space military technology, and has opposed past demilitarisation efforts. In 2006, the George W Bush administration blocked a United Nations resolution on arms control in space, issuing a National Space Policy that pledged to resist “new legal regimes or other restrictions,” including arms control agreements, on US use of space.

In response to this and other steps, other countries have moved to shore up their own space capabilities.

China tested an ASAT in 2007. Both it and Russia have increasingly invested in counter-space capabilities, such as ASAT technology and jamming GPS receivers. China and Russia’s advances left Washington spooked.

In 2014, the Pentagon invested an extra US$2 billion in classified offensive space programs. In 2015, the “emerging threats” of Russia and China were used to justify a $3 billion add-on for national security space capabilities, as officials openly talked about fighting a war in space.

But while in-orbit ASAT weapons exist, for the time being any space conflict would be fought from the Earth. For example, all three countries have capacity to disrupt enemy satellites by jamming them with their own, or to hack into a satellite’s ground operation.

But increased reliance on satellites for warfare — not to mention everyday life — opens up “a critical vulnerability”, warns the Centre for Strategic International Studies (CSIS). Space infrastructure is fragile, vulnerable to hacking and able to be brought down by other spacecraft intentionally ramming into it, by ground-based ASAT missiles or even by loose pieces of debris.

Because space is unfamiliar terrain, nations don’t know how to interpret others’ behaviour. According to Cassandra Steer, an independent consultant on space security and former executive director of the McGill University Centre for Research on Air and Space Law, when the US and its allies run war games centred on space, they can quickly escalate to nuclear war.

“If one major power thinks the other is about to take out its satellites, it could take reciprocal action, or even launch a conventional or nuclear attack,” says William Hartung, director of the Arms and Security Project at the Center for International Policy.

As space becomes increasingly cluttered with spacecraft, the chance of accidental calamity increases. Pentagon officials warn that space is becoming increasingly crowded. The US alone operates 859 government and commercial satellites, nearly one in five of which is military.

For the first time, two satellites collided in February 2009, producing a “debris cloud” that added to the approximately 500,000 pieces of debris currently in orbit, threatening to tear through spacecraft and add yet more debris. The destruction of spacecraft by ASAT tests, too, adds to the debris.

The more debris in orbit, the greater the threat to the non-military use of space that makes modern life possible. Traffic lights, banking systems, telephones, the internet, plane travel — all rely on satellites.

Back to Earth

Given these dangers, many diplomats and activists are pushing to declare space a weapon-free global commons. But there’s been little movement on any legally binding agreement.

Although “weapons of mass destruction” have been banned in space since the 1967 Outer Space Treaty, international regulation is sparse.

In 2008, Russia and China put forward a draft treaty on the Prevention of the Placement of Weapons in Outer Space (PPWT). Project Ploughshares called the PPWT “undoubtedly the most substantive effort thus far” to make weapon-free space a matter of international law. The US, however, said it couldn’t support such a “fundamentally flawed” proposal.

Many analysts say a treaty is unlikely in the near future, and look to other avenues of demilitarisation.

A more realistic solution, Steer says, is non-binding instruments like guidelines that regulate conduct in space, which can work due to political buy-in and reciprocity. These norms might include, for example, best practices on approaching another country’s spacecraft.

The US could be amenable to such agreements. John Hyten, commander of the US Strategic Command and a proponent of the Space Force, has urged the creation of “international norms of behavior in space”.

Space profiteers

The deeply vested interests involved, which have the ear of US politicians, also make it difficult to roll back or halt the militarisation of space.

The National Space Council, a group of cabinet members who shape US space policy, has a “users’ advisory group” whose members include the CEOs of Lockheed Martin, Boeing, Northrop Grumman and other corporations.

The Aerospace Industries Association (AIA), a trade group that counts these and other companies as members, funded the 2018 CSIS report calling for government investment in national security space assets. It has called for greater national security investment in space at the annual Space Symposium.

The Symposium, now in its 34th year, embodies the close ties between industry and government on space policy. Co-sponsored by the AIA and its defense contractor members, the Symposium offers a chance for industry to network with representatives of think tanks and educational institutions, foreign leaders, and military, national security and other government officials.

This year’s event in April featured speeches from Pence, Commerce Secretary Wilbur Ross, US senators and Air Force officials.

Industry influence extends to the politicians who advocate further space militarisation. Republican Representative Mike Rogers, reportedly instrumental in selling Trump on the Space Force, has received hundreds of thousands of dollars from the defense industry. Republican Representative Doug Lamborn and Democratic Representative Adam Schiff, both big boosters of a more aggressive space policy, represent districts populated by the defense industry and have raked in similarly large donations.

The Space Force contributes to this build-up, further entrenching militarisation and feeding money to defense contractors.

“President Trump’s enthusiasm for the Space Force,” Hartung says, “creates a danger that existing norms, like keeping weapons out of space, are more likely to be set aside.” He says the resulting space arms race “could spark a general war”.

Yet before efforts to rein in weaponisation can gain momentum, public awareness must be raised. This task is made harder by widespread media derision of Trump’s Space Force proposal.

Conflict in space is a clear and present danger. We need to take it seriously.

[Abridged from In These Times.]