The Tasmanian Greens recently announced a new policy to privatise the retail arm of the state-owned energy company Aurora, saying “a bit of good competition will almost certainly mean lower prices”.

Below, New Zealand activist and socialist Grant Brookes warns that a similar energy policy in New Zealand was a disaster.

As for the electoral fortunes of the Tasmanian Greens, I don't know enough about state politics there to comment with authority, although I very much doubt that the majority of people who voted Green will support this move.

What I can say for certain — based on two decades of experience — is that these reforms will not lower power prices.

From the late 1980s, right-wing Labor and National governments in New Zealand pushed through a series of almost identical reforms. The publicly owned energy generation assets were divided up. A minority were privatised, but most were given to three state-owned corporations, which then competed to sell electricity in a newly created energy market.

What happened? Well, customers who buy in bulk got lower prices. That's how markets work, right? So Rio Tinto (which takes a full 15% of New Zealand's electricity for its aluminium smelter in Southland) negotiated long-term supply deals with these power generators (the latest one runs until 2030).

The details of the deals are top secret, but enough info has leaked out that we can be sure the price per kilowatt-hour is less than a third of what ordinary householders pay.

Other big corporations have also seen their power bills fall in real terms. On average, the unit price for industrial customers is now less than half that paid by domestic consumers like you and I. We've been hit by rises averaging 8% a year for the last decade – the biggest in NZ's history.

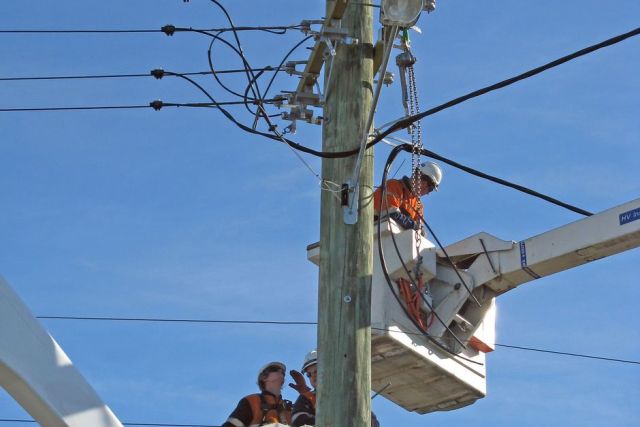

The transmission and distribution companies (the NZ equivalents of Transend and Aurora) were also restructured along competitive, market-driven lines.

What happened? They streamlined, cut costs, and got lean and mean by sacking their maintenance workers. They moved towards a contracting model, buying in skills on an as-needed basis. Many of the workers decided that moving to Australia was a better option than waiting by the phone. Executive remuneration, on the other hand, went through the roof.

Then the suits decided they actually didn't need maintenance very much at all. So in 1998, the high voltage cables bringing power into Auckland failed (as the maintenance workers had warned, before they were sacked) and the CBD of NZ's biggest city was plunged into darkness for five whole weeks.

Because, you see, the same government had meanwhile reformed higher education along market-led lines as well. So we had an explosion in the number of lawyers and accountants graduating from universities. But apprenticeships — a cost to business that efficient markets cannot abide — and trade training collapsed.

So in 1998, New Zealand had to import electrical maintenance workers from Australia to fix the Auckland power cable.

I am quite sure that much of this will come to pass in Tasmania if market forces are unleashed there on energy generation, distribution and supply. Cheaper deals for bulk buyers, cutting maintenance costs to boost the bottom line, mimicking private sector executive behaviour — all of these things are features of market-driven systems.