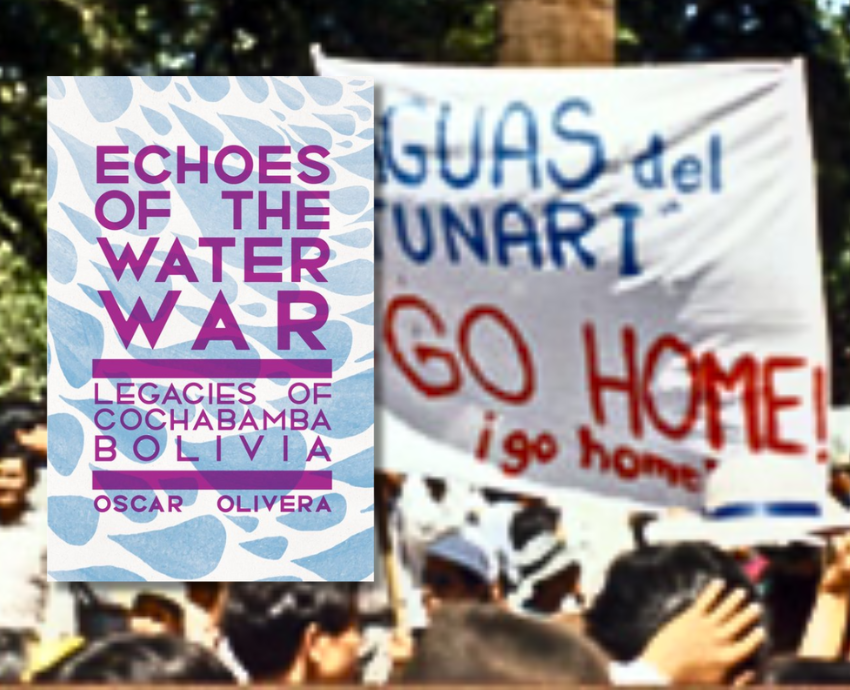

Echoes of the Water War: Legacies of Cochabamba, Bolivia

By Oscar Olivera

Common Notions, 2025

208pp

The 1999–2000 Water War is remembered as an emblematic grassroots struggle in Cochabamba, Bolivia, that successfully defeated neoliberal attempts to privatise control of the city’s water.

Oscar Olivera, one of the movement’s leaders, published a first-hand account in 2004 of how the movement organised against the privatisation — titled Cochabamba! Water War in Bolivia. A new edition, published by Common Notions and released 25 years after the struggle, contains Olivera’s original chapters and brings together additional authors’ contributions reflecting on the legacies of the Water War.

Echoes of the Water War traces the United States-sponsored imposition of the neoliberal economic model on Bolivia, starting in the mid-1980s and deepening in the 1990s, which privatised state-owned industries, destroyed labour conditions and dramatically lowered living standards.

The World Bank made privatisation, including of Cochabamba’s water system, a condition of loans to the Bolivian government in mid-1999. Later that year, the Bolivian government passed Law 2029, which effectively made traditional and autonomous water systems illegal, including collecting rainwater without permission.

As part of the privatisation law, the government signed a 40-year contract with Aguas del Tunari — an international consortium mostly controlled by the US-based Bechtel Corporation — to control Cochabamba’s water. Following the takeover, water bills rose by as much as 300%.

The most contentious points of the law, Oscar Olivera writes, were “the monopolistic character of the concession contract, the arbitrary level of consumer cost, and the confiscation of wells and alternative systems of use”.

Many protesters, writes Olivera, “first and foremost opposed the expropriation of their ability and legitimacy to manage water according to their traditional and customary practices”. This was evidenced in the hundreds of community-based water organisations that joined the protest from areas not directly affected by the privatisation contract.

Coordinadora

The principal organisation in the Water War was the Coalition for the Defence of Water and Life (Coordinadora), which brought together environmental groups, farmers, peasants, teachers, neighbourhood associations, blue- and white-collar workers in the manufacturing sector, local water committees and urban neighbourhood water cooperatives. It formed with the collective aim of avoiding water being privatised under the control of Aguas del Tunari and defending independent community-run water systems.

Olivera writes that the Coordinadora emerged from the region’s “ordinary inhabitants”, who “called upon the whole population to join in the struggle … based on understanding the importance of joint actions and believing that no individual sector alone could marshal sufficient strength to block the privatization of water”.

Olivera was a union leader in the Cochabamba Federation of Factory Workers (Fabriles), which was struggling against the neoliberal assault on workers’ rights and conditions in the 1990s, and became a key part of the Coordinadora. Fabriles provided material support to the Coordinadora, including the use of its headquarters in Cochabamba’s main square as a hub for meetings and organising.

‘Citizen’s union’

Olivera played a leading role in the meetings and assemblies of the Coordinadora, as well as acting as a spokesperson and representative. He characterises the Coordinadora as a “citizen’s union”, which aimed to build a mass movement based on direct participation and democracy.

Olivera details the impressive organisational capacity of the movement, which involved a series of mass meetings and assemblies — essentially spaces for community participation. These were scaled up to cabildos (town meetings) attended by 50–70,000 people in public plazas, where final decisions were made about the movement.

Echoes of the Water War details the tactics employed by the movement, such as mass rallies, marches, blockades, strikes, rate-payment boycotts — where residents symbolically ripped up or burned their unfair water bills — and a popular referendum.

Olivera writes that the “most important role of the Coordinadora” was to “build bridges between important sectors and leaders in Bolivia”. It brought together Indigenous Aymara communities, lowland coca growers, industrial workers, El Alto residents — a highland city next to La Paz — and other urban sectors, to successfully organise protests in “absolute coordination”.

Despite heavy police and military repression, the people’s uprising continued. Nearly the entire population of Cochabamba, along with many rural communities, participated in what Olivera describes as a “semi-insurrection” over February 4–5, 2000.

The mass blockades, strikes and demonstrations paralysed the city and forced the government into negotiations it had previously refused.

“We enacted a siege on imposition, on business, on resignation, on individualism,” writes Olivera. “And, at the same time, a recovery of human beings’ deepest values, which we believed the system had expropriated from us: solidarity, reciprocity, respect, transparency, mutual confidence, and a grand ayni [collective effort].”

By April, about 100,000 people had mobilised to finally win the expulsion of Aguas del Tunari and the modification of Law 2029.

Reflecting on the Water War 25 years afterwards, Olivera writes that it was “made possible by the people’s ability to self-organize, to deliberate in an assembly-based, horizontal manner … with a horizon that demanded democracy, because democracy, at its core and in simple terms for the people, is about ‘who decides’.

However, Olivera paints a disheartening picture of the years following the Water War, which did not ultimately result in water sovereignty and autonomy in Cochabamba. The current situation in the city remains largely similar — less than 50% of the population has a regular water supply.

Movement Toward Socialism

The incredible social upsurge in Bolivia during the Water War, and successive 2003 Gas War against the sell-off of natural gas resources, is arguably what swept the left-wing Movement Toward Socialism (MAS) party and President Evo Morales to power in 2005.

The book criticises MAS’s co-option of social movements and its top-down approach to managing national resources for undermining autonomous community water management.

Olivera writes that “Privatisation is, above all, expropriating, taking away, and dispossessing something that is common and managed for the common good.” In this sense, he criticises successive MAS governments for privatising water by “stripping away and removing the autonomous management of water exercised by the communities”.

Not all readers will agree with certain characterisations of the MAS government, such as that Morales’ presidential victory in 2005 was “the beginning of the defeat of the experiment begun in Cochabamba”.

While there are certainly valid criticisms of MAS governments, particularly in Morales’ later tenure and the final Luis Arce years, equating them to previous neoliberal governments overlooks the huge gains for ordinary Bolivians.

While stopping short of fully nationalising Bolivia’s gas industry, MAS massively raised royalties, using revenues to fund social programs, expand healthcare and education programs and reduce poverty. Between 2006–18, the MAS government cut poverty by 42% and extreme poverty by 60%, while also raising literacy rates and life expectancy.

The MAS had to contend with a relentlessly hostile oligarchy that worked to undermine any progressive gains — with the full support of the US government, which funnelled millions of dollars to opposition groups and backed multiple coup attempts.

Any progressive government in the Global South is forced to operate within the constraints of the global capitalist system, which systematically stunts and destroys attempts to improve the lives of ordinary people. This is no different in Bolivia, one of the poorest countries in Latin America, long subjected to colonial exploitation and integration into the global economic order as a primary commodity exporter.

To squarely attribute blame for Cochabamba’s little-improved water situation on the MAS overlooks the material conditions it had to contend with in attempting to improve the lives of ordinary Bolivians.

Nevertheless, Echoes of the Water War is a valuable contribution to the insights and lessons to be learned from the struggles against neoliberal onslaughts, especially given Bolivia’s current political context.

The new right-wing Rodrigo Paz government, whose election last November marked the end of nearly 20 years of the MAS in power, has already embarked on a series of neoliberal proposals. These include cutting public spending by 30% this year, eliminating high-wealth taxes and “reviewing” state-owned companies — usually a precursor to privatisation.

While Bolivia’s grassroots movements are certainly at a weaker point compared to previously in history, the recent strikes and roadblocks against Paz’s decision to cut fuel subsidies show that Bolivians will continue resisting neoliberalism.