The Black players on the University of Missouri's football (gridiron) team — a team in the national title hunt just two years ago — went on strike against racism on November 7.

The players demand was simple: they would not play until school president Tim Wolfe resigned over his inability to address a series of racist incidents on campus.

The strike had the potential to cost the Southeastern Conference football program millions of dollars — all because the conditions for Black students on campus have become simply unendurable. On November 9, Wolfe stepped down after months of protest over his administration's handling of racist incidents.

Two days earlier, 30 Black Mizzou football players, some with their arms interlocked, sent out the following message: “The athletes of colour on the University of Missouri football team truly believe 'injustice anywhere is a threat to justice everywhere' We will no longer participate in any football related activities until President Tim Wolfe resigns or is removed due to his negligence toward marginalized students' experiences. WE ARE UNITED!”

One player, who asked not to be named, told me: “We see what's happening here. We felt stupid saying and doing nothing while all this was going on around us. We want to be leaders on this because it affects us too.”

The power of this action cannot be overstated. These football players forced people to educate themselves about a campus environment that has been on fire for months, if not years.

This year activists on campus have protested over the rights of adjunct professors, the cutting of healthcare benefits, the rolling back of reproductive rights for women and a hostile climate for students of colour. And a recent series of ugly racist incidents led the football players to take collective action.

For a team that, two years ago, stood in solidarity with teammate Michael Sam when he told the world he was gay, they again made the lionhearted decision to rise to the moment.

The roots of racism at Mizzou run deep and reach back much farther than the last year. But this wave of struggle was sparked by what has been seen as the absence of response from the administration over the police killing of unarmed African American youth Michael Brown last year in Ferguson, Missouri — just two hours from campus.

Students gathered in great numbers on campus grounds to ask why Black lives didn't seem to matter to the administration. These demands, and a series of incidents of racial harassment of black students, were met with apathy by Wolfe.

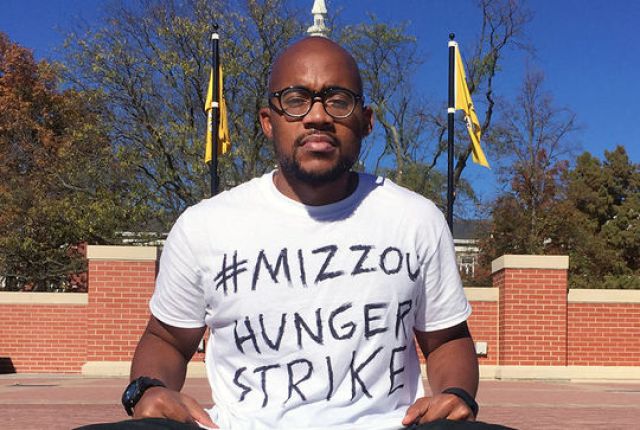

It reached a breaking point on October 24 when a swastika was smeared in faeces on the wall of a dormitory bathroom. In response, graduate student Jonathan Butler announced on November 2 that he was going on a hunger strike to demand Wolfe step down. Football players took up his demand.

The football strike mattered because the Missouri football players — like all big time college football players — hold deep social power. The student body is just 7% Black, yet 58 of the school's 84 scholarship football players are African American.

There is no football team without Black labour. That means there are no million dollar coaching salaries without Black labour. There is not a nucleus of campus social life without Black labour. There isn't the weekly economic boon to Columbia, Missouri, bringing in millions of dollars in revenue to hotels, restaurants, and other assorted businesses without Black labour.

The power brokers of Columbia need these games to be played. Yet if the young Black men and those willing to stand with them — and there are white teammates publicly standing with them — are not happy with the grind of unpaid labour on a campus openly hostile to black students, they can take it all down. They can do it just by putting down their helmets, hanging up their spikes and folding their arms.

Wolfe's resignation shows how university power really works in a country where football coaches are often the highest paid people on campus and universities are like a company town whose primary business is football. The actions of these players is best understood as a rumble of the sleeping giant.

[Abridged from Edge of Sports.]

Like the article? Subscribe to Green Left now! You can also like us on Facebook and follow us on Twitter.