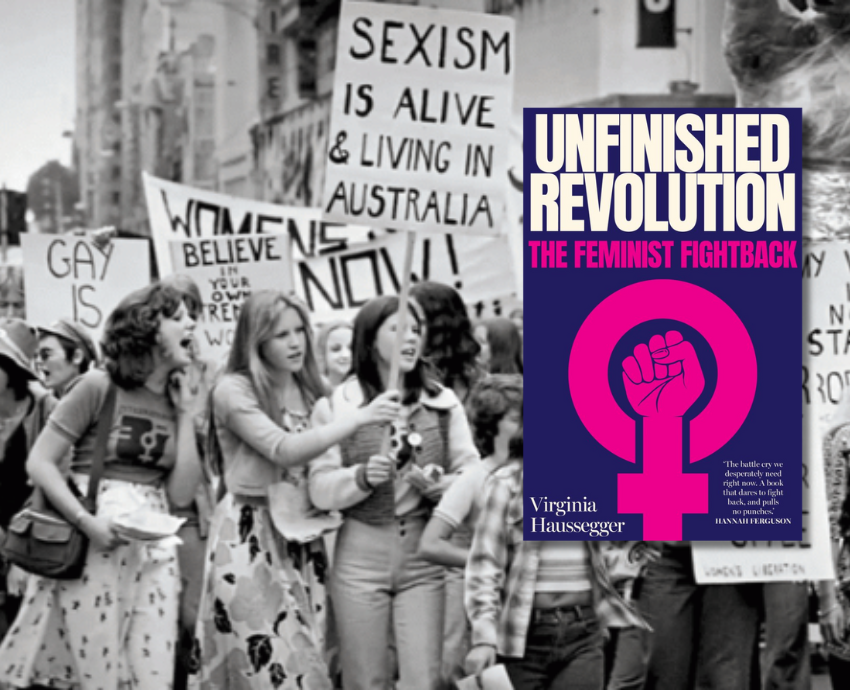

Unfinished Revolution: The Feminist Fightback

By Virginia Haussegger

UNSW Press, 2025

400pp, RRP $36.99

Australian journalist and academic Virginia Haussegger ends her second book, Unfinished Revolution: The Feminist Fightback, with a section titled “A Conclusion With No End”. This section and the book’s title summarise a central contention: that the fight for women’s liberation must continue, and that young women in particular are ready for the fight.

Haussegger refers to the present as the “New Now”, which she describes as “an unprecedented period of national consciousness raising”. She writes about the bold young women who have deepened that consciousness, especially about sexual assault and violence, coercion and rape culture. Their names are well known: Grace Tame, Brittany Higgins, Chantel Contos (founder of Teach Us Consent).

A momentous high point of the New Now was in March 2021, when more than 110,000 people — mostly women — participated in March4Justice rallies across Australia. These rallies were triggered by anger about workplace sexual harassment (including in federal parliament) and violence against women. Haussegger lists some of the messages on banners at these rallies, such as: “I can’t believe we are still protesting this shit”, “Ditch the Pricks” and “We will NOT BE SILENT #ENOUGHISENOUGH”.

As a journalist, Haussegger takes a critical look at the record of the media in aiding and abetting the patriarchy. She documents some of the outrageous attitudes towards women generated by the mainstream media and its hostility towards the feminist movement. Some revealing historical media headlines about International Women’s Year in 1975 include: “Giving the girls a go”; “$2mil. for the sheilas…” (the government funding allocated to women’s groups); and “The year of the bird”.

The author devotes much space to honouring the early 1970s’ women’s liberation movement. She focuses on her heroines, in particular Elizabeth Reid, who in 1973 became the first Women’s Adviser to an Australian prime minister — Labor PM Gough Whitlam. This was a first for Australia and the world.

Haussegger’s radical feminist politics means she gives little space to socialist feminists or their theories in her book. And yet socialist feminists have always been activists in the women’s liberation movement. For instance, in 1910, Clara Zetkin, a leader of Germany’s Social Democratic Party, called for an International Women’s Day to be held every year in every country to press for women’s rights. In Australia, the fight for reproductive rights was lead by socialist feminists.

Haussegger’s suggestion that a radical feminist theory and approach to fighting for women’s liberation has been the unique and singular method for success is one that socialist feminists would dispute. At the core of radical feminism is the idea that men are the problem and the cause of women’s oppression.

Haussegger repeats this view often: “The global manosphere spread the word faster than a virus”; “We know that men have always oppressed women — that much is clear”; and “Men are responsible. Yes, I know Italy’s prime minister, Giorgia Meloni, is a woman. So too are another nineteen of the 193 heads of government around the world.”

Many other female state leaders have not advanced and often actively blocked women’s rights, including British PM Margaret Thatcher, US Secretary of State Condolezza Rice, Zionist Golda Meir and Bangladesh’s ousted PM Sheik Hasina.

Former Australian Labor PM Julia Gillard is remembered for her “misogyny speech” in parliament, directed at then-opposition leader Tony Abbott. But earlier the same day, Gillard’s government cut welfare benefits to single parents — almost all of whom are single mothers.

And while Haussegger rightly criticises the Scott Morrison Coalition government, she ignores the actions of the Anthony Albanese Labor government. Despite women making up 55% of the cabinet, the government has allocated $368 billion to buying nuclear submarines and other weapons of war, while spending very little on or cutting services to aid survivors of domestic violence. It spends little on healthcare workers, education workers, aged care workers and disability workers — who are mostly women. Moreover, spending cuts to social services, such as the National Disability Insurance Scheme, disproportionately impact women.

So, while Haussegger’s book is a very good record of the women’s liberation movement in the ’70s, its underlying idea that radical feminism was the main and correct ideology is inaccurate.

The ’70s activist movement achieved many reforms through mass actions, discredited sexist ideas and changed how women saw themselves. However, the failure to correctly analyse the root cause as patriarchal capitalism led many in the movement to support politicians and political parties that were happy to maintain the capitalist system. No wonder, as one of the signs at the March4Justice rally declared, “we are still protesting this shit!”.