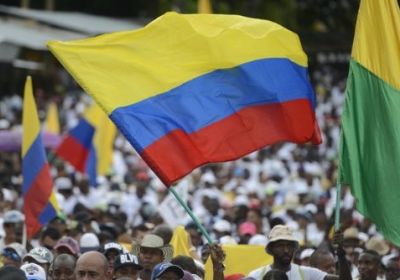

Colombia’s new government, led by President Gustavo Petro, has vowed to tackle violence and illegal mining, enact drug reforms and normalise relations with Cuba and Venezuela. Ian Ellis-Jones reports.

Colombia’s new government, led by President Gustavo Petro, has vowed to tackle violence and illegal mining, enact drug reforms and normalise relations with Cuba and Venezuela. Ian Ellis-Jones reports.

Australian-based solidarity group United for Colombia released the following appeal on August 3 in response to continuing human rights violations in Colombia.

Candlelight vigils were held in Colombia and cities around world on July 6 to demand an end to the political violence that since January has cost the lives of more than 125 social leaders in the South American country.

Political violence against social activists has risen in recent years despite the signing of a peace accord between the government and the leftist guerrilla group, the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia (FARC). According to Colombia’s Ombudsman, more than 311 political murders have been registered since the accords were signed in November 2016.

Colombia’s authorities seem unable or uninterested in curbing the wholesale slaughter of the country’s social leaders that has occurred since a peace process came into force, with nine leaders being murdered in the last week of June alone.

The violence is threatening Colombia’s peace process that not only sought the demobilisation of the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia (FARC), but also the increased political inclusion of the left and minorities in general.

In November 2016, as the Colombian government and the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia (FARC) met in Bogota’s Colon Theatre to sign an agreement – for the second time – to bring the country’s long-running armed conflict to an end, it was clear that peace-building in Colombia faced a myriad of challenges and obstacles.

The Colombian National Police massacred between 8 and 16 people, and wounded more than 50, in the municipality of Tumaco, Narino on October 5. The attack was directed against protesting coca growing families demanding the government fulfil its commitments to voluntary eradication programs.

Then, on October 8, the National Police attacked an international team sent to investigate the massacre. The police used tear gas and stun grenades to disperse representatives from the United Nations, the Organization of American States, and a journalist from the Colombian weekly, Semana.

Just days before he was set to speak at the 2013 Trade Union Congress (TUC) Conference in Britain, Colombian union leader Huber Ballesteros was arrested and imprisoned in his home country on trumped-up charges of rebellion and financing terrorism.

The National Liberation Army (ELN) has announced a temporary and bilateral ceasefire with the Colombian government.

The group said the ceasefire, agreed to in September during peace talks in Quito, Ecuador, will be implemented from October 1 to January 9, 2018.

Members of the National Political Council of the Revolutionary Alternative Forces of the Commons (FARC) rejected the threats and violence that have claimed the lives of 25 people since signing peace accords with the government last November.

“Since the signing of the peace agreement, five former combatants, nine militiamen and 11 relatives of members of the FARC have been murdered,” the group said in a statement on October 2.

Colombia’s communist army, the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia (FARC), relaunched itself as a political party on September 1 at a concert for “reconciliation and peace” in Bolivar Square, Bogota.

The guerrilla movement, which fought one of the longest civil wars in history until agreeing to a ceasefire with the government last year, confirmed its new name the day before at the end of its five-day congress.

It is now known as the Revolutionary Alternative Forces of the Commons, which will allow it to retain the FARC acronym.

"This is a fundamental precept of paramilitarism: clear the land to ensure smooth functioning for big business deals and, in this sense, this is no different to what has happened in the past few years in this country, which is the consolidation of what I would call a militarised neoliberal model, militarised in both a state and para-state sense."

An interview with Renan Vega Cantor, a professor at Colombia’s National Pedagogical University.

Jose Maria Lemus, president of the Tibu Community Board in Colombia’s North of Santander state, has been killed, the Peoples’ Congress reported June 14.

His murder adds to the growing list of recently assassinated social, Indigenous and human rights activists in the South American country.