The Australian government is pushing to deport the first Afghan asylum seeker since it signed a deal with the Afghanistan government in January last year to allow Afghan asylum seekers to be returned against their will. But a February 7 report by Fairfax journalist Rory Callinan revealed that a flagship $8 million resettlement project for deported asylum seekers — funded by Australia in a province outside Kabul — had fallen into chaotic disrepair.

At the same time, a pivotal High Court case challenged the government’s plans to forcibly deport failed asylum seekers, including Hazara refugee and Villawood detention centre detainee Ismail Mirza Jan.

Mirza Jan is the first Afghan asylum seeker the federal government has tried to forcibly repatriate since Australia and Afghanistan signed its memorandum of understanding (MoU).

The MoU, also signed by the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees, was the first mutual agreement between the countries to allow “involuntary” deportations of Afghan nationals. Immigration minister Chris Bowen said that without the agreement it “would be impossible to contemplate involuntary repatriation to Afghanistan”.

Part of the agreement said that Australia would fund resettlement programs, including “housing to stabilise and support the accommodation needs of landless Afghan nationals at AliceGhan”.

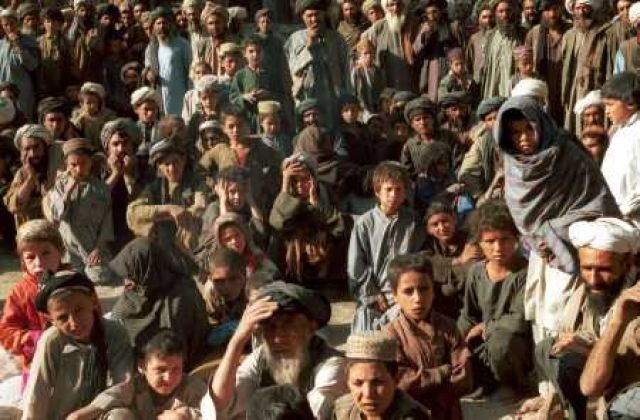

“AliceGhan” — named after the Afghan camel drivers who worked in central Australia in the 19th century — is about 50 kilometres north of Kabul. It was conceived by the Howard government in 2006 as a place for asylum seekers rejected by Australia. Partnered with the UN Development Project, it was to be a “housing settlement” with running water, jobs, schools and small businesses for 10,000 landless Afghans and internally displaced people.

In the memorandum’s annex, Australia agreed to “fund further initiatives at AliceGhan to see settlement reach its full potential”.

But, as Callinan reported on February 7, the project had foundered on corruption, bureaucracy and security problems.

Shockingly, the site has never had a permanent water supply. Due to a land dispute with a nearby village, water has been trucked in and collected by children.

And despite its agreement a year ago in the MoU, the immigration department confirmed to Callinan it had cut off funding until a “suitable water supply had been established by the UN Development Program and the Afghan government”.

AliceGhan was plagued with other problems. It was too far from work and had no medical clinic or basic sanitation. Even the houses were “culturally inappropriate”, with no boundary walls. Some were built without kitchens.

A progress report in 2009 said AliceGhan’s school was built without toilets because it was “not included in [the] school contract”. The 215 enrolled children instead used two pits dug about 40 metres from the school buildings.

Callinan said: “During the project’s development, there was an attempt to bomb aid workers as well as problems with land claims from neighbouring communities, fake refugees, squatters, a row over water rights and corrupt police seeking bribes from contractors.”

And “most of the programs and their trainees and potential jobs were non-existent and more than 600 of the 1025 houses were still vacant and falling into disrepair”. It was desolate, isolated and people sent there were leaving in favour of the slums and camps of Kabul.

He outlined several cables that AliceGhan project managers sent to Australia over 2007-08 that revealed the “frustratingly slow” progress and “mounting concern at delays”.

The Australian also reported on the AliceGhan project in mid-2010. One resident of AliceGhan said they had “tried to make houses like in Australia but we are Afghan and we have a different culture and we cannot live without walls around our compounds”.

It said AliceGhan has been used as “a guide on what mistakes can be made in resettling refugees”.

The Australian government is now trying to distance itself from AliceGhan. The February 8 Sydney Morning Herald reported that an immigration spokesperson said the department had ordered a $16,500 “needs assessment”. A spokesperson for Bowen said the project “had been planned and begun by the previous government”.

But despite this failure of the government’s flagship “resettlement” project, it is still pushing to open the legal gates on forced deportations.

The High Court challenge has argued that the immigration minister “failed in his duty of procedural fairness”, and that Mirza Jan and other asylum seekers should be able to challenge the minister’s decisions via judicial review.

The case has also held back the deportation of two Tamil refugees, after an injunction was ruled by a magistrate’s court until the High Court outcome.

Refugee Action Coalition spokesperson Ian Rintoul said in December: “The High Court case has the potential to be as significant for refugee processing as the M61 case last year that allowed offshore asylum seekers access to the Australian courts.

“It will open up even more of the determination process, previously kept behind the scenes, to legal scrutiny. But there will be no real justice until the government desists from forcibly deporting people to danger.”