Over the space of five months, the vast algal bloom in South Australia’s coastal waters has affected more than 450 marine species, devastating many of their populations. Commercial fishers and tourism operators have suffered severe losses.

There is nothing new about algal blooms, which occur from time to time when particular combinations of temperature, sunlight and nutrients allow aquatic microorganisms to multiply at exceptional rates.

But the current catastrophe is being described as completely unprecedented.

Is there something at play here apart from the normal workings of nature? Does the environmental disaster reflect a new state of affairs, likely to recur semi-regularly from now on? And are human actions, including government policies, in some way to blame?

In each case, the answer is clearly yes. But let’s start with some basics.

The main algal species responsible in this case is Karenia mikimotoi, first identified in Japan in 1935. Highly adaptable, this species tolerates diverse salinity levels and sea temperatures, though it favours warm, calm, sunny conditions. It thrives particularly amid decaying organic matter, which it creates for itself by secreting a toxin that disrupts nerve function in fish and many invertebrates.

The neurotoxin can be directly lethal to marine animals. But the main reason for the die-offs caused by Karenia mikimotoi blooms is reportedly that animals’ gills become inflamed and clogged with algae, resulting in inadequate oxygen uptake.

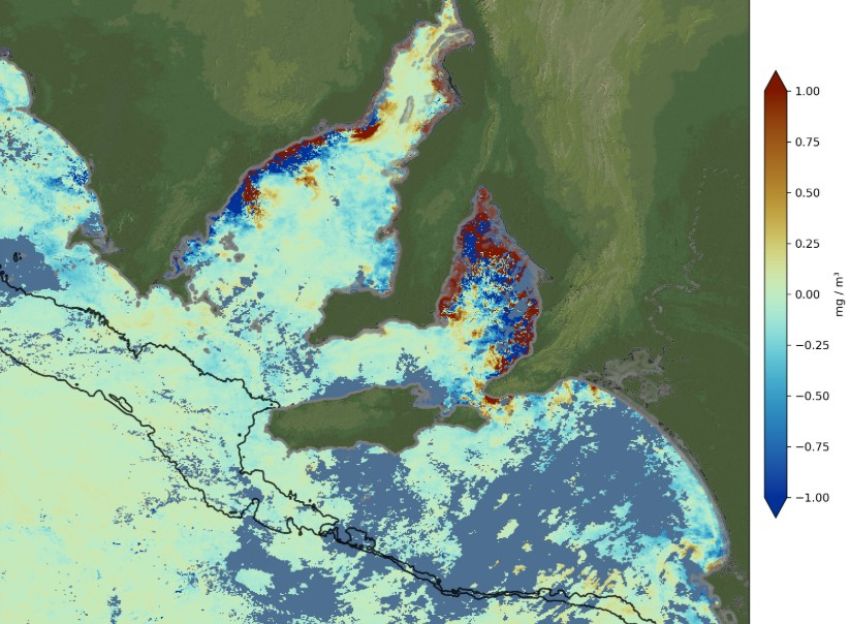

Relatively mobile fish species may be able to migrate to escape the algae. But with the extent of the bloom now calculated at 4500 square kilometres, this is often impossible. Great white sharks have been found washed up on local beaches.

Marine mammals are much less affected by the algae than fish, but may still die from eating prey that have ingested the toxin, or from respiratory inflammation and allergic reactions. Among the victims of the bloom have been seals, whales and dolphins.

Nor are humans completely exempt, with swimmers reporting coughing, shortness of breath and skin and eye irritations.

Along coastlines, the algae leave banks of thick foam. These emit aerosols that, when the breeze is right, cause distress to people as much as a kilometre inland.

Karenia mikimotoi, for all that, is a long-established part of South Australia’s marine environment. What accounts for its sudden proliferation?

Scientists have pointed to three factors: high levels of nutrients; extreme sea temperatures; and months of sunny, calm weather.

In 2022‒23, the Murray River experienced its biggest flood since 1956. Usually, the Murray barely makes it to the ocean. But this time, it poured large quantities of nutrients into the local marine environment. Further nutrients have since arrived with upwellings of deep water from off the continental shelf.

Normally, these conditions would be thoroughly beneficial, setting off an explosion of marine life. But throughout much of last year, and during the past summer and autumn, southern South Australia was in near-record drought. Storm systems were few and hot, and still days succeeded one another. The sea underwent little mixing and temperatures climbed.

A prolonged “marine heat wave” ensued, with inshore waters as much as 3°C warmer than usual. Under often cloudless skies, algal species that could take the heat photosynthesised at a furious pace. Meanwhile sea grasses and kelps, unable to cope with the temperatures, began dying and decaying. The situation was made for Karenia Mikimotoi.

With storms in the current winter, ocean temperatures off the South Australian coast have now fallen to near normal. But algal blooms, once established, can be remarkably enduring, lasting as long as 18 months. The South Australian bloom is still very much present, and Karenia Mikimotoi, as noted, is an uncommonly resilient species. As spring returns, water temperatures will climb again.

What are the dangers in the longer term?

Scientists are emphatic that marine algal blooms are closely linked to sea temperature and that rising ocean temperatures are in turn a key manifestation of global warming. This effectively guarantees more disasters for South Australia’s marine environment.

As global warming proceeds, the climate along Australia’s southern coast is predicted to become hotter and drier, with less cloud cover and fewer and weaker storms to disperse concentrations of algae. Karenia Mikimotoi will be back, with availability of nutrients the probable main limitation on its visits.

This fits into an alarming pattern worldwide.

A recent article in the journal Science reported that in 2023 marine heat waves engulfed 96% of the world’s oceans, breaking records for duration, intensity and scale. Researchers, the article noted, agree widely that human-driven climate change is causing the frequency and severity of marine heat waves to rise sharply.

The failures on climate policy of governments around the world have been brought home unexpectedly to South Australians.

Little as they may feel they deserve it, citizens are finding their walks along the beach are now eye-watering experiences, which require them to step around the cadavers of the state’s marine wildlife.