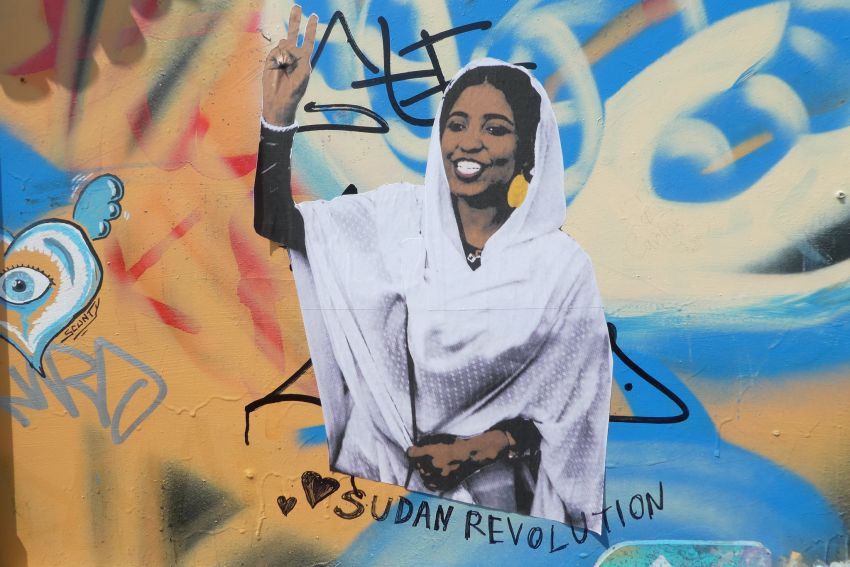

For eight months beginning in December 2018, Sudan was gripped by an unprecedented mass movement determined to overthrow the 30-year dictatorship of Omar al-Bashir.

In spite of brutal repression, this outpouring was overwhelmingly peaceful, disciplined and well organised. However, elements of the old regime, centred around the army, have sought to hang on to power.

In April 2019, a group of generals deposed al-Bashir in a coup d’état, creating the Transitional Military Council (TMC), in an effort to put themselves at the head of the process. Further mass protests took place, with more than 100 killed on June 3, as the army attempted to clear a two-month long sit-in in front of army headquarters. Enormous gatherings on June 30 finally forced the TMC into an uneasy transitional power-sharing agreement in mid-2019, with the democratic movement organised as the Forces of Freedom and Change (FFC).

Green Left spoke to Khalid Hassan about the immense achievement of the Sudanese people and the difficult challenges ahead. Hassan is a long-time member of the Sudanese Communist Party and a founding member of the Democratic Consciousness Forum, a Perth-based Sudanese community organisation.

The army

Hassan told GL the reason the Sudanese army was not able to quickly usurp the uprising and manoeuvre a new strongman into place, such as happened in Egypt or Algeria, is because the democracy movement had absorbed the lessons of previous upsurges that were crushed. Central to this has been its grassroots organisation through the Resistance Committees.

“The people who actually participated in the revolution are very well organised, especially the youth. In every suburb and village across Sudan there is a neighbourhood committee. This is where you find the leaders of the movement. This is one of the main achievements of the revolution.”

In every show of force with the army, this nationwide network mobilised to protect the new civilian administration. While the army acts as a constant brake on progressive reform, and would like to reinstate a dictatorship, Hassan doesn’t think they are able to, based on the current balance of forces. The civilian administration is pushing ahead with some very significant social reforms, however there is also rising frustration among its supporters with the slow pace of change. The FFC also faces huge and varied obstacles.

Al-Bashir’s closest supporters were organised around his political party, the Muslim Botherhood.

“Today, the Muslim Brotherhood has no influence over the army or on the streets,” said Hassan. “In fact, most of them are in prison.”

However, he estimates that about half of the dictator’s support base had a fairly pragmatic attitude. The fact that they abandoned him saved the country from an immediate all-out civil war, but they are now trying to regroup.

While there may be support for the democratic movement among the lower ranks of the military, the majority of the officers are aligned with the TMC. The military owns many of the country’s largest enterprises in its own right and traditionally gets more than 70% of the country’s budget.

“Many of the old regime’s former partners who were not ideologically committed to it switched sides,” said Hassan.

“They are just people who want to be in power.

“The generals have no interest in social reforms. They want to maintain the status quo. While military spending has been cut and more is going to health and education, they are still big economic players.

“They have money and the reality is they would like to seize power, but they are not strong enough to do it. Too many people would actively oppose the army trying to take over, especially the youth.”

The strength and organisation of the movement has kept the army at bay and largely eliminated right-wing gang violence. Another significant advance is the greater acceptance that Sudan is a multi-ethic and multi-religious society.

“There is no way we could go back to the old regime based on their version of Arab and Islamic ideology,” Hassan stressed.

“The rebel groups fighting the dictatorship in the South, around the Blue Nile, in the Nuba Mountains and in Darfur are among the biggest and strongest supporters of the revolution … there is no more fighting in these places.

“The army has reached peace agreements with a number of these forces and is negotiating with two others.”

Reforms for women

Regarding the place of women in society, Hassan said: “While they have still not made the gains that they deserve, there have been some very big changes to women’s legal status and we now have women in many senior positions.”

Reforms include the abolition of the crime of apostasy, the criminalisation of female genital mutilation, the removal of the requirements for women to seek permission from a male relative to travel with children, and the scrapping of public order laws that had governed women’s presence in public spaces.

Hassan said the biggest obstacle to further progress is women having the time and economic possibility to participate in public life.

Some of the challenges for the FFC come from within. Many of the key administrators in the new civilian government were not active participants in the revolution, but Sudanese technocrats and “experts”, with experience at international agencies like the World Bank or the United Nations. They tend to accept, without question, neoliberal economic prescriptions.

Such people were appointed to broker a compromise agreement among the former opposition parties, but, according to Hassan, the more radical democratic forces within the FFC believe this is now a serious problem.

This is compounded by regional and international powers, which have intervened on the side of the TMC or the more conservative forces within the FFC, with Saudi Arabia and the United States playing particularly destructive roles.

Sanctions

Subject to far-reaching US sanctions and indicted by the International Criminal Court, al-Bashir bought space for his regime by playing both sides of the fence in the region.

While mostly aligning with Qatar and Iran, he also made himself valuable to the Saudis by providing forces to fight in Yemen.

Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates quickly recognised the TMC leadership, seeing an opportunity to bring Sudan into their fold with the demise of the pro-Iranian Muslim Brotherhood faction within the ruling elite. The Saudis immediately offered US$4 billion in aid, but cancelled this when the TMC was forced to accept a civilian-led government.

Crippling sanctions were imposed in 1993 when the US designated Sudan as a “state sponsor of terrorism”. Consequently the country is cut off from the world financial system, and has to funnel all its imports and exports via other countries, imposing a huge cost on the economy.

The US accused Sudan of support for the al-Qaeda attacks on US embassies in Kenya and Tanzania in 1998, and the USS Cole in 2000.

However, it seems likely the real reasons for the sanctions was al-Bashir’s siding with Iraq in the 1991 Gulf War, his public support for Iran, and assistance to Hezbollah and Palestinian groups.

US President Donald Trump has proposed to lift the sanctions in return for Sudan paying US$335 million in compensation for the embassy and USS Cole incidents.

In keeping with the hypocritical double-speak surrounding the so-called “war on terror”, the US has never objected to Sudan providing troops to support the murderous Saudi intervention in Yemen. The Sudanese government remains dependent on its payments from Saudi Arabia for providing this service.

The al-Bashir dictatorship did not encourage the domestic production of manufactured or agricultural commodities to counter the sanctions, with its supporters content to profit from running import businesses.

The future?

Underlining just how desperate the situation is, Hassan said: “The new government has inherited a terrible budget and completely broken down infrastructure. It’s like they’re starting from scratch.

“It also has to cope with the coronavirus as well, with no international financial assistance. The European Union made some promises, but it looks like they have been pressured by the US not to help.

“A number of international agencies have said they will only give Sudan assistance if it removes its subsidies on basic commodities.”

While the government has maintained these subsidies, prices have still skyrocketed.

“People are really suffering, the prices for bread and fuel have increased by 500–600% since the fall of al-Bashir,” said Hassan.

“If things don’t improve within the next six months, then I think the people will take to the streets to change the government again.”

The more radical forces supporting the civilian administration have to frequently make tactical judgements about how and when to criticise it, striking a balance between trying to push it to be more democratic and responsive to the needs of the people, while not creating disunity at critical moments of confrontation with the army.

The Sudanese Communist Party actively participates in the broad democratic alliance, but reserves the right to advance its own independent position and criticise the transitional government. However in Hassan’s estimation, if serious progress can’t be made in improving the transitional government’s policies and practice, then the democracy movement may need to sweep it away and start again.

The extent of people’s frustrations will be revealed by the size of protests called for October 21.

“People feel that the process of change is very slow, that there still has not been justice for those that were killed, the economic situation is really bad and that the army still has too much influence,” said Hassan.

“For all these reasons I think the protests will be very big.”