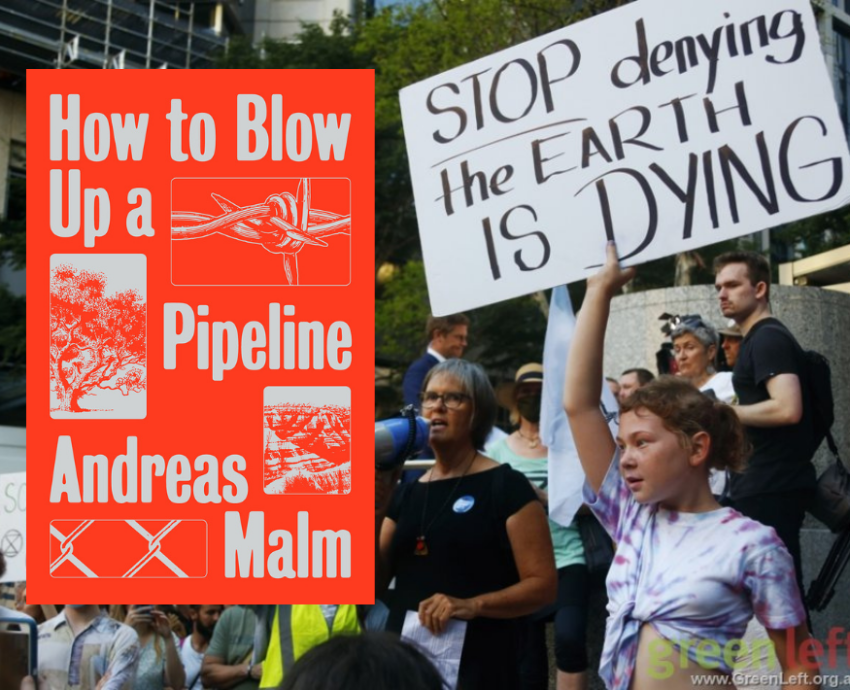

How to Blow up a Pipeline: Learning to Fight in a World on Fire

By Andreas Malm

Verso, 2021

Despite the climate movement’s growth, epitomised by Extinction Rebellion and Student Strike for Climate, fossil fuel extraction continues to grow, and a safe climate can seem dismayingly distant. Given a choice between forgoing capital accumulation and tipping the whole world into a furnace, our rulers prefer the furnace.

In How to Blow up a Pipeline, Andreas Malm asks how the climate movement can emerge from the COVID-19 hiatus as a stronger force. In particular, he questions whether the movement’s until now near-universal commitment to non-violent protest is holding it back. “Will absolute non-violence be the only way, forever the sole admissible tactic in the struggle to abolish fossil fuels? Can we be sure that it will suffice against this enemy? Must we tie ourselves to its mast to reach a safer place?”

To make his point, Malm cites examples of popular historic movements, some of which are invoked by today’s climate campaigners as examples of non-violent change.

The overthrow of Atlantic slavery involved violent slave uprisings and rebellions. The suffragettes of early 20th century Britain regularly engaged in property destruction. The United States civil rights movement was punctuated by urban riots. As part of the struggle against apartheid in South Africa, Nelson Mandela co-founded the armed wing of the African National Congress, [uMkhonto weSiswe — Spear of the Nation]. The Indian National Congress is known for its non-violent tactics, but violence also played a role in the resistance to British rule from the Great Rebellion of 1857 until independence.

Malm absolutely rules out violence that harms people, but he wants the climate movement to include sabotage and property destruction in its plans.

He puts forward several reasons why these kinds of protests might help “break the spell” of the status quo. Targeting the luxury consumption of the rich in this way could help to stigmatise the notion that the rich can blithely condemn the rest of us to ecological disaster. Physical attacks on new CO2 emitting devices might reduce their use and make them less popular options for new investment. He also speculates that such actions could help bring together a “radical flank” of the movement, helping to win partial reforms by making elites more keen to compromise with the movement moderates.

Malm believes such tactics could make for some powerful political symbolism: “Next time the wildfires burn through the forests of Europe, take out a digger. Next time a Caribbean island is battered beyond recognition, burst in upon a banquet of luxury emissions or a Shell board meeting. The weather is already political, but it is political from one side only, blowing off the steam built up by the enemy, who is not made to feel the heat or take the blame.”

Malm’s arguments have been met with alarm in some quarters. In a review posted on the Global Ecosocialist Network website Alan Thornett says adopting the book’s proposals would “not only be wrong but disastrous” and anyone who did so would soon have “armed police kicking down their door”. He calls Malm’s argument an impatient “bid for a shortcut” resulting from “frustration compounded by the lack of a socially just exit strategy from fossil energy”.

James Wilt’s review in Canadian Dimension is even harsher: he says How to Blow up a Pipeline “veers awfully close to entrapment” — a totally unworthy accusation. More to the point, Wilt says Malm doesn’t look deeply at the likely outcomes of his proposals, failing to mention any “planning for the inevitable backlash” and repression activists would face.

But, as Bue Rübner Hansen points out in a Viewpoint article, Malm’s “provocative title makes a pitch for viral controversy, but its contents are more nuanced and equivocal”.

Early in the book, Malm says that acts of property destruction should complement, not substitute for, mass movements for climate justice — disciplined and planned mass protests are still “the main way forward”. He writes: “The determination of the movement to scale up its challenge to business-as-usual by means of ever bigger, bolder mass actions of precisely this kind cannot be called into question.”

He recognises that acts of political violence and property destruction could alienate support, so “non-violent mass mobilisation should (where possible) be the first resort, militant action the last.”

Malm opposes reckless actions — “controlled political violence” should be regarded a “fine art to be mastered” and “time and timing are of the essence”. Because violent actions could backfire and “make a movement look so distasteful as to deny it all influence”, climate saboteurs must be “especially circumspect and mindful” of the wider cause, as the “negative effects could be unusually ruinous”.

He is very critical of the sabotage tactics of groups such as EarthFirst! and the Earth Liberation Front in North America in the 1980s and '90s. Their acts of “ecotage” produced “no lasting gains” because “they were not performed in a mass movement, but largely in a void”.

His opposition to “the temptation to fetishise one kind of tactic” includes “property destruction and other forms of violence”. Since “the tactic with the greatest potential for this movement might be something different”, political violence may not be useful for the climate movement after all.

Malm’s support for political violence is more limited and conditional than some of his critics suggest, but his fondness for provocative formulations must take some of the blame for any misunderstanding. A more accurate title would be Consider blowing up a pipeline, at the right time, after careful consideration, in ways that complement non-violent mass action; but don’t mess things up for others, definitely don’t hurt anyone, and maybe don’t do it at all — but of course How to Blow up a Pipeline attracts more attention and controversy.

What is radical?

Malm’s argument that non-violent protest and civil disobedience is a tactic rather than a permanent strategy is well made. The climate movement should not make a fetish of any particular type of action — but Malm’s repeated equation of “militant” protest with violence does not help the discussion.

No particular form of protest is inherently the most radical or militant. Actions that demoralise, divide or hinder the movement are not radical or militant, no matter what slogans are raised or how much property is destroyed.

The types of action Malm discusses — from deflating SUV tires to destroying fossil fuel infrastructure — appeal mostly to a minority who are already radical. It is easy to say that such actions must be an organic part of a wider climate movement, but hard to ensure in practice.

Rather than creating an influential “radical flank”, separating squads of dedicated property-wreckers from the majority who hold liberal illusions is most likely to isolate the left and strengthen the aggressively reformist, eco-modernist wing of the climate movement.

The most radical organisers are those who get more people into motion, helping ever larger numbers to engage in mass action to change the world and change themselves. The most revolutionary acts are those that create conditions in which people can deepen their political understanding and gain confidence in their collective political potential.

The best militants don’t lead by heroic individual example: they work to maximise experiences that make others more militant. The most important movement leaders are not the best speakers or the most selfless activists — they are those who make their own leadership redundant by facilitating the development of new leaders.

Malm is genuinely committed to advancing the climate movement, making it more radical and hence more effective at dealing with a crisis caused by capitalism, but his call for sabotage and property destruction by a minority is misplaced, despite the many qualifications he includes.

No matter how sincere it is, How to Blow up a Pipeline undermines the more radical strategy of bringing wider layers of people into struggle and helping them to see themselves as key protagonists in this fight for the future.

[Reprinted from Climate and Capitalism. Simon Butler is co-author of Too Many People? Population, Immigration and the Environmental Crisis.]