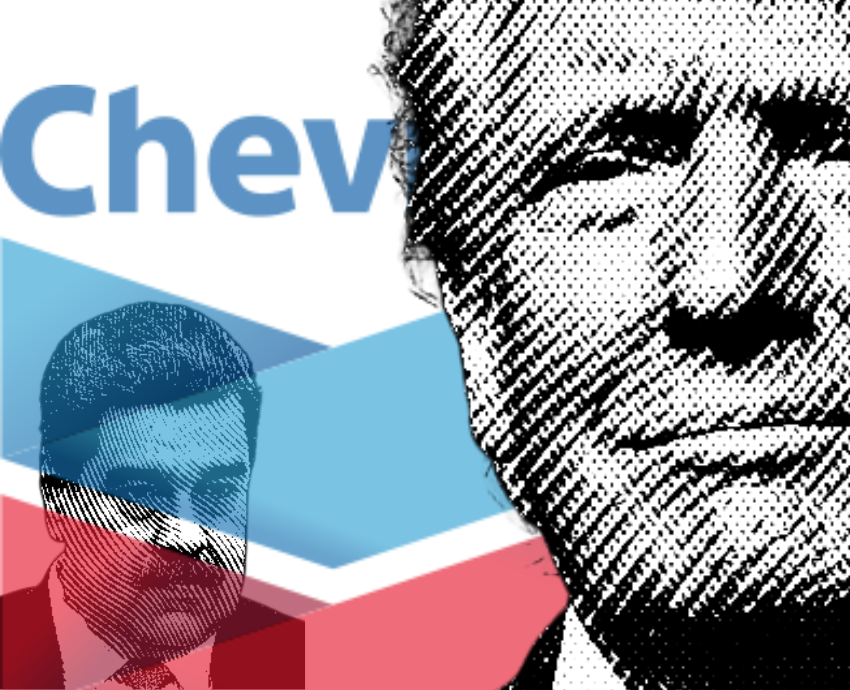

United States policy towards Venezuela took another surprising turn with the announcement that US oil giant Chevron could return to the South American nation.

Granting Chevron a licence to exploit Venezuelan oilfields represents a turnabout from statements made in February by US Secretary of State Marco Rubio, a traditional Republican anti-Communist hardliner whose support base is among Miami’s right-wing Latin American community.

Back then, Rubio said he was working to terminate “oil and gas licences that have shamefully bankrolled the illegitimate [Nicolás] Maduro regime.”

Shortly after, Chevron had its licence revoked and was given until late May to wind down operations.

Previous US governments have steadily increased sanctions on Venezuela over the past decade, which have greatly exacerbated the country’s economic crisis and taken a huge humanitarian toll on the country.

With US oil companies completely barred from operating in Venezuela in 2019, national oil production dropped from more than 2 million barrels a day just a few years earlier to as little as 350,000 barrels in 2021.

The partial easing of sanctions resulting from negotiations over Venezuela’s presidential elections saw the US Treasury’s Office of Foreign Assets Control allow Chevron to exploit Venezuelan oil in partnership with Venezuela’s state oil company PDVSA under restricted conditions in 2023.

Together with other measures, this enabled PDVSA to lift oil production to about 1 million barrels today, a figure expected to increase by 200,000 in the short to medium term with Chevron’s new license.

Many expected the US government to again tighten sanctions when Venezuela’s National Electoral Council controversially declared Maduro winner of the July 28, 2024, presidential election while refusing to release results validating its disputed claim.

Newly elected US president Donald Trump threatened to do that early on in his term, but his approach in practice has taken a different tack.

Trump surprised many in May, sending Special Envoy Ric Grenell, seen as more aligned with his “America First” orientation to foreign policy, to Caracas to directly negotiate with Maduro. The meeting led to six detained US citizens being freed and Venezuela agreeing to accept deportation flights carrying Venezuelan migrants from the US.

Though no specific oil deal was announced at the time, Grenell explained that meeting Maduro was about putting “America first and do[ing] what’s best for America. That means making sure that the Chinese do not take the Venezuelan oil.”

Shortly after, Trump and Rubio resumed talk of sanctions and rejecting Grenell’s call to extend Chevron’s wind down period beyond May. But it was not clear whether this was actual policy or a negotiation strategy.

The latest events indicate the latter was the case, with Trump deciding to prioritise access to Venezuela’s oil, according to a July 24 article in the Wall Street Journal.

At a specially convened meeting in mid-July, Trump spoke with Rubio, Grenell and other senior officials, urging them to “work for a deal giving priority to American companies’ access to Venezuela’s oil deposits…

“During the meeting, he acknowledged that this went against Rubio’s longtime opposition to engaging diplomatically or financially with … Maduro, but made it clear he wanted a deal anyway...”

Days later on July 18, another deal was struck, with 10 US citizens held by Venezuela being swapped for more than 250 Venezuelan migrants illegally sent by the US government to El Salvador’s notorious Terrorist Confinement Centre, CEDOT.

While no details have been released regarding the licence, a senior state department official claimed that Maduro’s government would not profit from it.

However, Maduro’s interior minister Diosdado Cabello quickly shut down this idea, saying on July 30: “Does anyone really believe they are going to come here, extract oil from Venezuelan territory, put it on a ship, take it, and not pay Venezuela anything?”

Cabello added that the licence was “private in nature”.

“Only Trump, the Venezuelan government, and Chevron are the only ones who know its scope and conditions. Anything else that the corrupt media says is pure fiction.”

The Maduro government has the ability to sign secret contracts under the Anti-Blockade Law, approved in 2020. Justified as a measure to protect businesses willing to defy US sanctions, the law is now used to keep hidden dealings with the US government and US oil multinationals.

Such deals contravene Venezuela’s constitution, which require all contracts of public interest to be debated and approved by the National Assembly.

Despite the new deal, US Attorney General Pam Bondi accused Maduro of being “one of the largest narco-traffickers in the world” and announced the reward for information leading to his arrest would be doubled to US$50 million, on August 7.

The accusation follows the US administration’s decision to designate drug cartels as “foreign terrorist organisations” and authorise the Pentagon to use military force against them.

Arresting Maduro would require direct US military intervention — something that would be deeply unpopular at home.

Government officials from various countries and left movements within Venezuela have spoken out against the move.

Colombian President Gustavo Petro warned any foreign military intervention would be treated as an aggression against all of Latin America.

Petro has taken a firm stance against regime-change tactics, instead calling for dialogue, the lifting of sanctions and new elections in Venezuela.

Communist Party of Venezuela (PCV) leader Neirlay Andrade said on August 12 that Bondi’s announcement “contributed nothing to resolving the deep political crisis in our country” and warned “criminal sanctions will only worsen workers’ living conditions”.

“US imperialism continues to act as the global cop, preparing the ground for interventions that have already had disastrous consequences in Latin America and other regions.”

Andrade called on the Venezuelan people to reject the idea that foreign interference could restore democratic rule in the country.

The PCV also warned that these announcements by US officials were being used by Maduro’s government to justify repression “against the popular, working-class and revolutionary movement”.