Green Left’s Federico Fuentes sat down with Mariana Riscali, a leader of the Socialist Left Movement (MES) tendency inside Brazil’s radical left Socialism and Freedom Party (PSOL), to discuss the nature of the new Workers’ Party (PT) government, the ongoing threat posed by the movement around former far right President Jair Bolsonaro and the state of the country’s trade unions and social movements.

How does the current government of President Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva compare with his previous governments (2004–08, 2008–12)?

Before the first Lula government, and even during it, some on the left — not us, but others — held out hope that his government would be more progressive. They saw it as the first chance for the left to govern for the people.

This time, however, Lula clearly ran as the candidate of a wider democratic front. His vice presidential candidate was Geraldo Alckmin, who was originally from a centre-right party. Lula presented himself as a democratic candidate who could unite the forces required to defeat far-right President Jair Bolsonaro, rather than some kind of left alternative.

Bolsonaro is part of a broader international trend of rising radical and far-right parties. How does MES view this broader phenomenon?

Bolsonaro is definitely part of this broader movement, as is Argentina’s new president, Javier Milei.

One of the most important issues globally right now — Israel’s genocide against the Palestinian people — is the result of the strengthening of the far right, as [Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin] Netanyahu is part of this international far-right trend.

In Europe, we have also seen the growth of radical right organisations such as Alternative for Germany, Brothers of Italy and Chega! in Portugal. These parties have won support on the basis of combining liberal economic ideas with authoritarian and fascist politics.

In terms of possible differences — at least between Brazil and Argentina — one is that, here, we did not see large street mobilisations against Bolsonaro. The united front against Bolsonaro was built from above by parties that united at election time to defend democracy.

Hopefully in Argentina, which has a history of struggle and where the working class is more organised, the left will be able to mobilise people on the streets against Milei.

Bolsonaro has consolidated himself as the main leader on the Brazilian right. How did he achieve this?

Bolsonaro managed this by successfully tapping into an existing anti-system sentiment. He did not just base himself on traditional far-right ideas, such as family values, religion and anti-LGBTIQ. He presented himself as standing against the old way of doing politics.

He says: “We are against the system.” It used to be the left that said “we are against the system”, but now it is the far right that uses this discourse to push their conservative alternative.

By combining this discourse with clever use of social media to enable him to reach the maximum number of people, Bolsonaro was able to engage with sectors who feel everything is bad and expand his support base beyond the traditional right.

In other countries where the far right is strong, the radical left has often made alliances with parties of the political establishment to defeat the far right. Is there not an inherent weakness in such an approach, as it cedes the anti-system sentiment to the right?

Generally speaking, the left faces a tough situation internationally. It has found it difficult to grow, which has allowed the far right to build itself. The right has also managed to grow where the left has won elections, because the left has generally not managed to govern for the working class. We need to break this cycle if we want to build alternatives that can grow and challenge for power.

But I think we made the correct decision with the presidential election. We had to support Lula, even if this meant accepting Alckmin as Lula’s vice president, because there was no other way of defeating Bolsonaro. We knew that if Bolsonaro won we faced the danger of a profoundly anti-democratic process.

But now that Lula is in government, we see no need to enter into government with these same sectors. We are now in a different moment, which requires different tactics.

So what is PSOL’s relationship with the PT now?

There are two distinct positions within PSOL on this issue: those who want to move PSOL closer to the government and those opposing this.

Supporters of the first stance — a majority within PSOL — argue the far right is still very strong. This is true. Bolsonarism is a broader movement with elected representatives at the federal, state and municipal level, and poses a real threat.

But they use this to argue that we need to lower our expectations and demand less of the Lula government; they say that we should not publicly criticise Lula, as this will only help the far right.

MES believes that if we do not criticise what needs to be criticised, if we do not point to alternatives, if we do not point out that most of Lula’s policies benefit financial sectors and the upper classes, then, when people become disappointed with Lula’s government for not resolving their problems, they will again see the far right as the only alternative.

Could you give us a sense of the state of struggle in Brazil?

We are not in a period where social struggles are in the ascendancy — I think this is true not just for Brazil but internationally.

On top of this, the PT’s hold over trade unions and important social movements has meant an important part of the social movements have argued we should not be mobilising to demand more from the government because “it’s our government” and we need to give Lula more time to govern.

So, we have not seen many struggles on the streets.

Another common trend internationally is declining trade union membership. Is this the case in Brazil?

Yes, unions in Brazil, like the rest of the world, have been getting weaker.

But it is also important to note some important examples in recent years of gig economy workers starting to self-organise. They are not formally organised as unions; instead, they are developing new forms of worker organisations.

Those organisations are still at an embryonic stage, but they have organised some very interesting mobilisations. Through this we have seen the emergence of new leaders, similar to what we saw with Amazon workers in the United States.

What is the situation with the Landless Workers Movement (MST)?

During Lula’s first year back in government, the MST — one of Brazil’s most important social movements — played a crucial role in raising the issue of land reform. For this, the MST has become a target of the right, which initiated a Parliamentary Commission of Inquiry into the movement in an attempt to criminalise the MST over its land occupations.

The PT’s policy of governing with agribusiness interests will inevitably lead to more contradictions between Lula and the MST, as occurred during his first two terms in government. But the MST leadership is very close to the PT, and tends to avoid key debates in the name of maintaining support for the government.

This has led to some more radical sectors leaving the MST to build organisations that are more loyal to the MST’s original principles.

The struggle for Black and women’s rights have gained strength in recent years. Was this largely a reaction to Bolsonaro?

Bolsonaro is part of explaining this, but we have also seen similar movements arise globally, for example with Black Lives Matter in the United States.

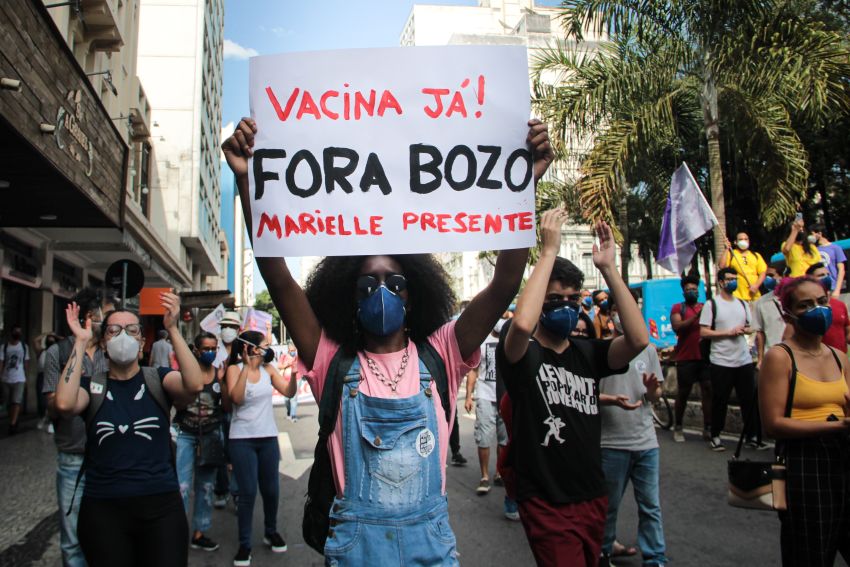

You could say the women's movement in particular grew in response to Bolsonaro — there was a strong reaction by women who were the first to mobilise against Bolsonaro through the #EleNao (#NotHim) movement. But again, I think this fits in with what we have seen internationally in terms of the rise of women's movements.

For sure, Bolsonaro motivated these movements due to his positions against women, the LGBTI community and Blacks. But these new movements are not simply a reaction to Bolsonaro.

What is the relationship between these new movements and the PT?

These movements are definitely more independent from the PT than, for example, the traditional trade union movement, given the PT’s strong history within the trade unions. In some cases, PSOL has more influence within these movements than the PT.

[Abridged from a longer two-part interview published at links.org.au.]