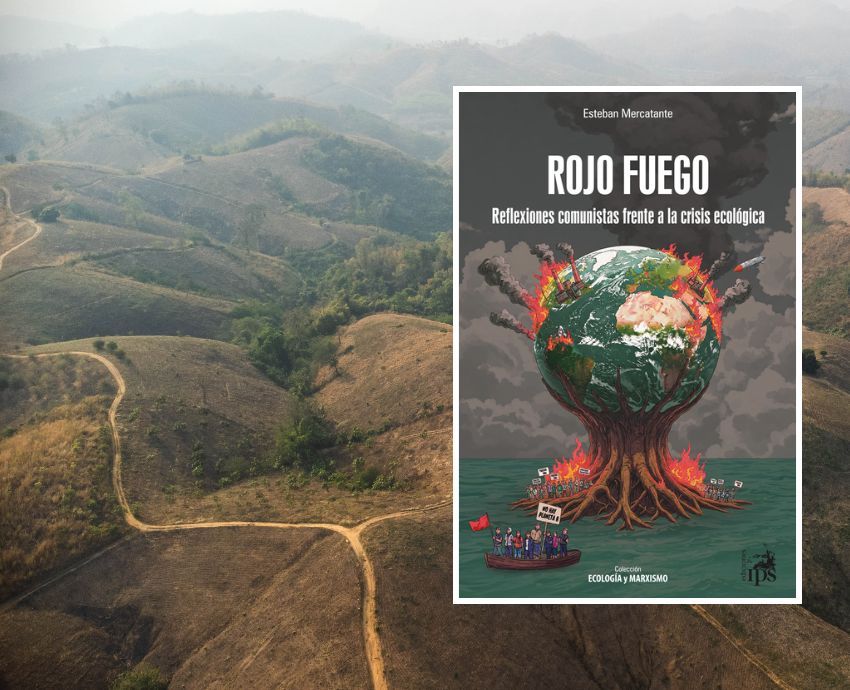

Fiery Red: Communist reflections on the ecological crisis

By Esteban Mercatante

Ediciones IPS

216pp

In his new book, Fiery red: Communist reflections on the ecological crisis, Argentine Marxist Esteban Mercatante takes aim at capitalism while arguing the case for an “ecommunist” strategy.

Green Left’s Federico Fuentes spoke to Mercatante, an editorial board member of Ideas de Izquierda (Left Ideas), about his book.

What made you write your book?

I wanted to introduce a Marxist perspective — which is not as accessible for Spanish speakers — into the discussion, particularly here in Argentina.

Most eco-Marxist works produced in the past decades, from the early contributions by John Bellamy Foster through to the more recent writings of Kohei Saito and Andreas Malm, have been relatively little discussed. I wanted to synthesise some of these contributions.

There are also questions that eco-Marxists need to further develop their ideas on, and I wanted to contribute to that too.

I also wanted to look at the ways in which Karl Marx’s critique of political economy can help expose the anti-ecological character of capital accumulation.

Part of the book reconstructs the different phases of production and circulation of capital, from capital-labour relations to the formation of a world market based on increasingly accelerated flows of commodities and money. This can help us think through how different ecological problems are generated at each stage of this cycle.

Lastly, there is another key question that Marxism has struggled to address — and which we need to debate — and that is how to link our ecological critique of capital to a revolutionary strategy for transcending capitalism. This is a major weakness in the otherwise important contributions by Foster, Saito and others.

More recent attempts have sought to deal with this challenge, for example, Malm’s call for an “ecological Leninism”. But, as refreshing as his approach is, his view that the revolutionary seizure of power is not on the agenda today leaves his proposal somewhat floating in the air.

My book aims to contribute to a fundamental discussion on how to develop, from an ecological perspective, a revolutionary strategy around a communist vision that both seeks to liberate humanity from exploitation and restore a balanced metabolism between society and nature.

Your book looks at different currents within ecosocialism. What are these main currents?

Broadly speaking, these currents tend to be polarised between proponents of degrowth and advocates of an anti-capitalist or ecomodernist accelerationism.

The main target of degrowth — as its name suggests — is economic growth, which is identified as the main cause of the ecological crisis.

Their argument that what we face today is over-consumption — and that resource extraction far exceeds the planet’s capacity to replenish what is extracted — makes sense when talking about developed countries.

They raise concepts such as the “imperial mode of living”, which says rich societies live beyond sustainable limits at the expense of the rest of the planet, from which they extract resources and offload the costs of environmental impacts.

This raises an interesting issue by inserting imperialism into the ecological question.

But, at the same time, degrowth contains several problems.

Discussion tends to go down the path of questioning consumption rather than production itself, which, beyond any intentions, slightly blurs the systemic root of the problem.

The working classes in rich countries end up being viewed as participants in this “imperial mode of living” — or, at least, are not explicitly excluded. This is despite multiple indicators showing a marked deterioration in their living standards in recent decades, due to privatisation and global economic restructuring.

This does not mean the burden of responsibility should be equally shared. Inequality is a very important aspect of these views. Moreover, questioning the notion of economic growth as an end in itself, as degrowthers do, is important.

But there are big weaknesses in degrowth perspectives in developing consistent alternatives.

They say there must be qualitative changes in how things are produced, but struggle to come up with concrete measures. The quantitative emphasis — reducing the scale of production and consumption — is the only thing they clearly articulate.

There are also differences among exponents of degrowth on the alternative. Some authors, such as Serge Latouche, are directly hostile to the idea of socialism. Others argue that a steady-state capitalist economy may be possible, and that therefore degrowth and capitalism are not inherently antagonistic.

There are also those with more anti-capitalist views, such Jason Hickel or Saito, the latter of which explicitly advocates for degrowth communism.

Notwithstanding these nuances, what characterises these visions is their focus on a kind of minimum or immediate program, conceived as demands on the state.

They include some interesting issues — such as reducing the working day — but are not combined with a transitional perspective, or something resembling a strategy to transcend capitalism.

Standing opposed to these positions — in an almost mirror-like fashion — is ecomodernism. From this perspective, the answer to the ecological crisis lies in accelerating technological development.

Aaron Bastani’s book Fully Automated Luxury Communism is a prime example. In Bastani’s view, freeing technological development from the constraints imposed by capitalist relations of production would make it possible to fully automate production processes and come up with innovations that can solve environmental problems.

The problems capitalism generates are simply reduced to a lack of planning.

For ecomodernists, there is almost no limit to the so-called decoupling of the economy from the environment — that is, ensuring the least possible impact in terms of resource extraction and waste production.

They base this on the claim that this has been occurring under capitalism in more developed countries. But it is less decoupling, than the offshoring of production processes to third countries, through which environmental impacts are “outsourced”.

Once we take this “offshoring” into account, the scale of decoupling is largely reduced, if it does not disappear altogether. Putting faith in an automated luxury communism based on such weak assumptions can only lead to ruin.

Precisely because they do not want to put all their eggs in one basket, they say that if we cannot achieve enough decoupling, then the answer lies in space mining and using outer space as a dumping ground.

Ecomodernists think more in terms of eliminating labour rather than transforming it. This shows itself in the absence of the working class as a subject with any role to play in its emancipation or establishing a different social metabolism.

They hope that the system’s contractions, worsened by the kind of accelerationism they propose, will produce a post-capitalism that enables planning, along with the “democratisation” and extension of the consumption patterns of the rich to the rest of society.

Given these patterns cannot be made universal within the finite limits of the planet, it is not surprising they have to conjure up intergalactic solutions to environmental challenges. What we are left with then is a (luxury) “communist” variant of the kind of space ravings of Elon Musk or Jeff Bezos.

You argue the case for an “ecommunist” perspective. What is ecommunism?

The term ecomunismo comes from the title of Ariel Petruccelli’s latest book, which foregrounds the central issue that ecological Marxism or ecosocialism must emphasise.

Instead of debating whether “solutions” will come from technology or reducing metabolisms, we need to organise the needed social forces to attack the foci of ecological destruction: capitalism and the relations of production this exploitative social order engenders.

Ecomodernists and degrowthers talk about reducing the working day, but what is missing is the protagonism of labour as an agent in its own emancipation and in the qualitative transformation of society’s relationship with nature.

Under capitalism, production-consumption is a differentiated unity mediated by the process of exchange. Only by socialising the means of production, can we re-establish a genuine unity of both processes, in which production is based on satisfying social needs.

This is a key aspect that can help us break free from the polarised debate between “more” or “less” that has dominated discussions among ecosocialists.

Communism has at its heart the transformation of labour and its relationship with nature. This is the cornerstone for recovering all the potential denied to labour by the alienated relations imposed on it by capital and, at the same time, for ending the abstraction of nature. These are the preconditions for moving from the realm of necessity to the realm of freedom.

I am not proposing any magic bullet for dealing with the dangerous ecological crisis that capitalism will leave behind. The more sober proposal I am making is that there is no need to delude ourselves with the techno-optimistic Prometheanism of “fully-automated luxury communism”, or resign ourselves to the hardships advocated by degrowthers.

On the contrary, achieving a society based on the democratic deliberations of all workers and communities, and on planned social production through socialisation of the means of production in the hands of a minority of exploiters, can create the conditions to allow us to meet the twin objectives of (re)establishing a balanced social metabolism while fully satisfying social needs.

[Abridged from a much longer version of this interview published at links.org.au.]