In the run-up to June’s parliamentary elections, the political atmosphere in France has been transformed by a new left alliance, the New Popular Ecological and Social Union (Nouvelle Union Populaire Écologique et Sociale, or NUPES). It has provoked much enthusiasm, and considerable criticism.

How useful is it, and what are its prospects?

Just over a month ago, between the two rounds of the French presidential elections, the news was filled with depressing “debates” between conservatives and fascists about how best to defend the rich and mistreat Muslims. But after the second round, the radical left managed to regain the initiative by forming an electoral alliance and launching an ambitious campaign for the legislative elections in June.

Under the French system, while significant powers are vested in the president, it is the grouping that has a majority in the National Assembly that forms government and selects the Prime Minister. It is not unusual to have periods of uneasy “cohabitation”, when the party of the president is not part of the parliamentary majority.

Electoral politics is a distorted reflection of class struggle. For the last 20 years, France has been the stage for regular social explosions. Among them was the mass strike movement against Socialist Party President François Hollande and his 2016 labour law, a law which worsened millions of people’s employment contracts. More recently was the successful revolt against Macron’s attack on pension rights, although Macron has indicated he will try again; and, of course, there was the impressive Yellow Vest rebellion.

These movements inspired and educated millions, and showed a high level of class consciousness. In the case of the attack on pensions, half of the strikers were acting to defend the conditions of future generations, not their own. They were generally defensive in nature, reacting against vicious government attacks, sometimes from right-wing governments, sometimes from Socialist Party governments. It is the relatively high level of class consciousness and combativity which has allowed the rebirth of left reformism in a radical and insurgent form — the France Insoumise.

Of course, life would be easier for Marxists if people involved in these exciting and painful class struggles all realised at the same time the need to overthrow capitalism and eliminate forever the dictatorship of profit. But this is not the way of the world, and most were thinking, “How can we get a government that doesn’t attack us?” and, “Surely we can get a government which is on our side for a change?”

Millions now feel the NUPES is the answer to this question. Formed by Jean-Luc Mélenchon and the France Insoumise, after Mélenchon’s impressive score of 7.7 million votes in the May presidential election, it involves other left parties roughly in proportion to their presidential scores: notably the Greens (who got 1.5 million votes), the French Communist Party (800,000) and what is left of the Socialist Party (600,000).

The aim is to win a parliamentary majority in June and apply radical reforms. As a result, the TV discussions are now, to our delight, filled with questions about raising the minimum wage by more than 15%, raising all public sector salaries by 10%, allowing people to retire at 60, taxing the rich and freezing prices on basic foods and fuel.

The NUPES has published a list of 650 proposals, adding up to what Mélenchon describes as “spectacular change”. Other key measures include ending nuclear power, 100,000 new hospital jobs, and “refounding the police” in response to frequent police violence against demonstrators and ethnic minorities.

The France Insoumise representatives elected in 2017 were already different from most MPs: a care worker, a librarian, a radical journalist, a leading fighter against Islamophobia — all rare sights elsewhere in the National Assembly. NUPES is now presenting some new candidates who symbolise grassroots revolt: for example, Rachel Kéké, one of the Black leaders of a very long hotel cleaners’ strike; and Stéphane Ravacley, a baker who hit the news when he went on hunger strike to stop the expulsion from France of his young Black apprentice.

The coalition aims at winning a majority in parliament in the June elections. Arguing that Macron only won because people were voting against his fascist opponent, the NUPES leadership say it is the left that can win the legitimacy to govern the country.

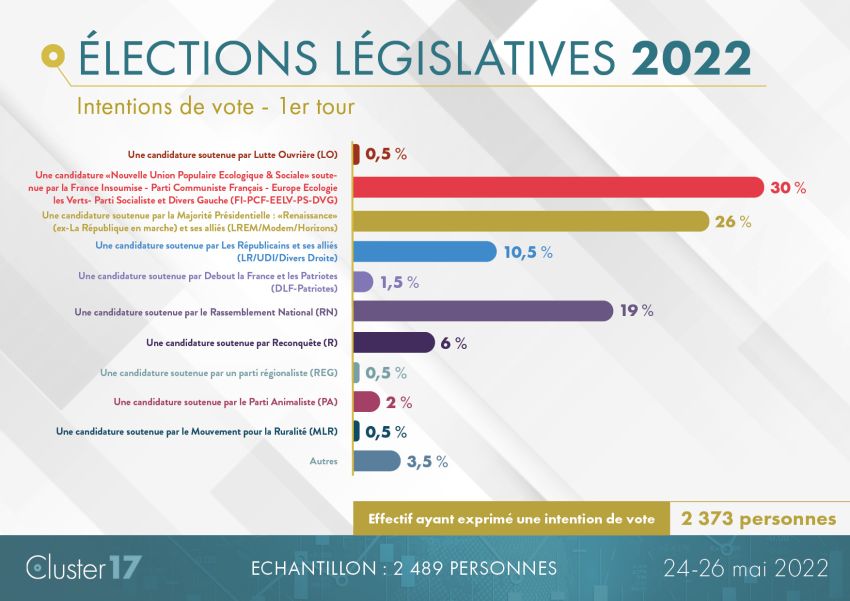

Mélenchon’s program is popular, and a mid-May poll by major TV channel TF1 put NUPES leading first-round voter intentions at 28%, as against 27% for Macron’s candidates and 22% for the far-right. Winning a parliamentary majority is nevertheless an uphill struggle for NUPES, since in the second round of a two round election, those who voted fascist in the first round will often support Macron’s party. Yet in the last parliamentary elections, in 2017, more than 20 million people stayed at home on election day. If the radical left can mobilise those who usually abstain, everything is possible.

Enthusiasm

The most important effect of the launching of the new coalition has been a rise in enthusiasm among voters and activists and the dynamic of the presidential campaign has continued, with neighbourhood meetings in every town and much door to door canvassing. It is a mass campaign of mobilisation and education.

Nevertheless there are points of tension. Many feel that, although the slate of candidates is less white and elite than usual, it should be considerably less white still, and include more grassroots activists.

In addition, the inclusion in the NUPES alliance of the Socialist Party (PS) as a junior partner — which will stand as NUPES in 70 of the 570 constituencies — has been controversial. Many NUPES supporters say that this has allowed NUPES to make the most of the real roots that the PS has in a few regions, and that the PS signing up to the key points of the NUPES program will accelerate the crisis within it and may even see its right wing leave. They say that, in this way, NUPES has no real opposition on the left, and that this unity can help build the mass dynamic needed to win.

Others on the left consider any agreement with the PS — even though the latter is weakened — to be unacceptable, and may be the beginning of a drift rightwards.

Many Marxist activists are involved in the NUPES campaign, and three fairly small revolutionary groups work with it — two producing their own paper. But the biggest — though not very big — far-left group, the New Anticapitalist Party (NPA), is very much divided on the question. It has allowed each NPA branch to decide whether to support NUPES locally or not.

Hope and danger

The objective of NUPES is to use the state to limit the power of capital. It is not to break this power. And certainly there is no shortage of dangers.

First, well-funded media smear campaigns and right-wing movements could push NUPES backwards and help the right wing win. Secondly, in case of a victory by the NUPES alliance, the huge powers of international capital will move into action to stop the program being put into practice by the new government. Thirdly, an intermediate result, in which NUPES was able to form a government only by allying with forces to its right, would put strong pressure on NUPES leaders to hugely water down the program.

Many NUPES activists are aware that mass mobilisation is key to limiting these dangers. Mélenchon himself insists that one of the main reasons for the relative failure of Mitterand’s radical left government in the 1980s was the lack of popular mobilisation. Naturally, only Marxists go one step further and insist that such mobilisation must eventually aim at a new kind of state that can definitively break the power of capital.

But for Marxists to persuade people of this, they need to be part of the present movement for spectacular change. The situation does not need guardians of the pure revolutionary flame without fuel, whose ambition is to say “I told you so” more poetically than other activists. In a situation where most workers do not have a clear idea what a socialist revolution is, or how to distinguish it from the “citizens’ revolution” called for by Mélenchon, it is essential to be able to defend our ideas while building the struggle for radical reforms alongside many thousands of others.

A terrified elite

The ruling class, in any case, is terrified. Media scare and smear campaigns are running hot. The front page of the principal conservative weekly, Le Point, says Mélenchon is “another Le Pen”, “a charlatan” with “a taste for dictators”, while another says “Mélenchon thinks he is the messiah”. On the television, Mélenchon is presented as “a dangerous man”, the NUPES as a “monstrous radicalism” which “submits to Islamic fundamentalism”, an alliance which is “outside of democratic rules” and is “an insult to democracy”. One leading member of the right wing of the PS claimed Mélenchon would make France into North Korea, another complained that by joining the alliance, the PS was “selling its soul to the monster”.

Macron and the right, meanwhile…

Macron had promised that his second term “will not be a continuation of the term just finished” but a “réinvention”, a “complete renewal”. Still, after his cabinet reshuffle and change of prime minister in late May, Le Monde headlined “Macron chooses continuity”. Under pressure from his left, he made two choices that he hoped would satisfy the less right wing of his supporters.

First, he appointed a woman Prime Minister, Elisabeth Borne. She claims to see herself as “a woman of the left”, but no one else appears to have noticed, and her past record includes organising the partial privatisation of French railways, and being a key player in Macron’s plan to smash the French pension scheme.

Secondly, Macron appointed a Black historian as minister of education. Certainly not a left-wing man, Pap N’diaye has nevertheless spoken out against the ridiculous Islamophobic campaigns led by the previous minister, Jean-Marie Blanquer, who had claimed that French universities were dominated by scary “Islamoleftists”. This is a welcome step backwards for the Islamophobes, who are under much more pressure since Mélenchon’s party moved to defending Muslims.

They are on the offensive elsewhere though. A huge row has blown up over the decision of the Grenoble city council, who voted to authorise in council swimming pools the full-body swimsuits which some Muslim women wear. Racist regional governments responded by announcing they would cut funding to any swimming pools that made this decision. The state took the question to the courts in an emergency session and the council was ordered to suspend the authorisation of this piece of clothing in swimming pools. Although the subject may seem trivial, it has given rise to a major racist campaign presenting Islam as incompatible with women’s rights and democracy.

The reaction on the left is poor. Despite the important steps forward in recent years, which have led to Mélenchon now defending Muslims regularly and publicly against Islamophobia in general terms, the left still has a long way to go. Almost all national leaderships of left organisations have avoided committing themselves on the issue because their organisations are divided. Mélenchon declared he should “not be expected to comment on the rules of swimming pools”. The NPA newspaper avoided the issue too.

A key fight

After the billions spent on the pandemic, and determined not to tax the rich, Macron — if his party wins another majority in the National Assembly — will turn the austerity program up even higher. Recent polls show that for 46% of French people, poverty and wages or, as the pollsters quaintly put it, “pouvoir d’achat” (buying power), is the number one issue in the forthcoming elections, polling far ahead of any other question. The NUPES campaign for spectacular change is providing hope and education to huge numbers of people. It needs everyone’s support.

[John Mullen is a Marxist activist in the Paris region, and a supporter of the Nouvelle Union Populaire Écologique et Sociale.]