There have been nearly 600 First Nations deaths in custody since the final report of the Royal Commission into Aboriginal Deaths in Custody (RCIADIC) was tabled in 1991. Thirteen First Nations people have died in custody this year — 28% of total deaths in custody — a massive over-representation of First Nations people, who only make up 3.8% of the total population.

The RCIADIC was limited in scope, failed to properly identify the systematic racism at the heart of the issue and did not result in the prosecution of any of the killers in the 99 cases that it investigated.

But it made 339 modest, and entirely practical, recommendations for reforms that could reduce, if not eliminate, First Nations people’s deaths in custody. Yet, after 34 years, these reforms have yet to be fully implemented.

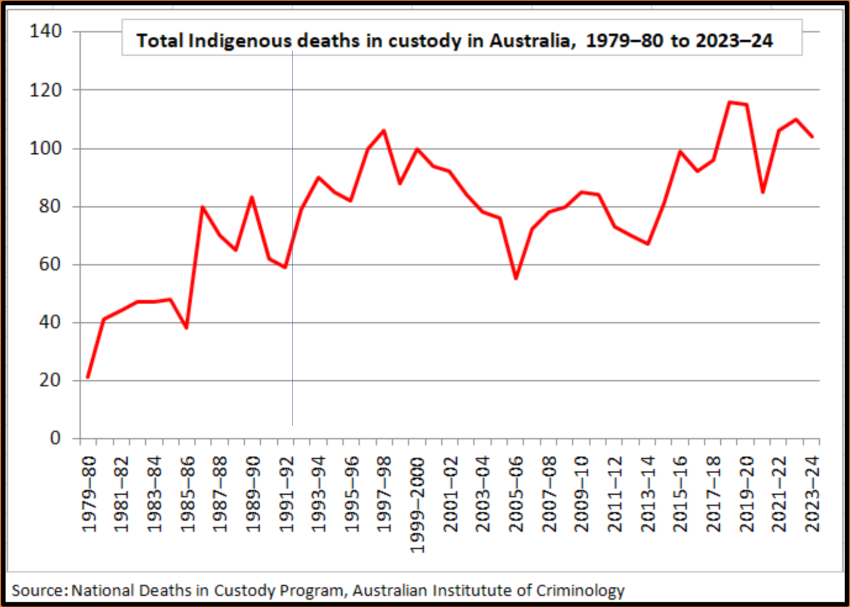

After initially falling after the RCIADIC, First Nations deaths in custody have been rising sharply again.

This is because the main cause, as the RCIADIAC identified, is the higher incarceration rate of First Nations people.

The Australian Bureau of Statistics reported on June 30 last year that 36% of all prisoners in Australia were Aboriginal or Torres Strait Islander.

So, was it worthwhile for First Nations and allied activists to put so much time and energy into campaigning for a royal commission back in the 1980s?

My answer is: Yes.

John Pat

On September 28, 1983, 16-year-old First Nations youth John Pat was killed by off-duty police in Roebourne, in the Pilbara in Western Australia. The autopsy revealed a fractured skull, haemorrhage and swelling, as well as bruising and tearing of the brain.

John Pat had sustained a number of massive blows to the head.

One bruise at the back of his head was the size of the palm of a hand, and there were many other bruises visible. In addition to the head injuries, he had two broken ribs and a torn aorta, the major blood vessel leading from the heart.

Jan Mayman, an independent journalist from WA, went to Roebourne and covered the trial in more detail than any mainstream journalist. This drew nationwide attention to the issue.

But the alternative media, including Direct Action (the forerunner to Green Left), also played a significant role.

One two-page story I wrote for Direct Action on John Pat’s brutal death in 1984 had a wide impact; the Northern Territory Land Council ordered a bundle of that issue.

Very few First Nations deaths in custody have made it to trial. In the John Pat case, an all-white jury eventually acquitted the police of manslaughter in 1984. Thirty years after John Pat was killed, however, the WA government made an apology to his family.

No cop or prison warden has ever been found guilty of a First Nations death in custody in Australia.

In September 1984, the Committee to Defend Black Rights (CDBR) was formed, initially to highlight John Pat’s death, but it also prompted other families to speak out too, such as Eddie Murray’s, who died in police custody in 1981 in Wee Waa, New South Wales.

It was First Nations-led, and mainly by women, such as Helen Ulli Corbett, Karen Flick, Rose Stack and Rosemary Wanganeen.

Later Cathy Eatock and her brother Greg joined CDBR. Their mother, Aunty Pat Eatock (a veteran of the original Aboriginal tent embassy in Canberra and Socialist Alliance member) also played a leading role in the 2000s.

From the beginning, some non-First Nations activists were very active in the CDBR, among them Vanessa Forrest and Matt Davies.

The CDBR empowered the victims’ families, among them younger activists who would later play leading roles in later phases of the campaign against Black deaths in custody and other First Nation rights campaigns.

Uncle Ray Jackson, another First Nations socialist and trade unionist also set up the Aboriginal Deaths in Custody Watch Committee (ADICWC), which worked hand-in-hand with the CDBR.

In September 1986, CDBR organised a national speaking tour featuring members of some of the family members of those who had been killed to share their stories.

Corbett also addressed the United Nations Working Group on Indigenous Populations in August 1987 in Geneva. She pointed out that First Nations deaths in custody recorded that year alone by the CDBR had added up to one every 14 days.

She also pointed out that if the same rate of death in custody were happening for the population as a whole, there would be 1500 deaths in custody a year!

The CDBR also worked to educate international networks, including through the Nuclear Free and Independent Pacific, Indonesia, South Korea, Amnesty International in Britain, and even in Cuba, alongside protests and public meetings around Australia.

On August 9, 1987, a mass public meeting organised by CDBR and ADICWC filled Sydney Town Hall.

The next day, then Labor Prime Minister Bob Hawke announced a royal commission into First Nations deaths in custody.

Over the four years of the royal commission, the CDBR worked relentlessly to mobilise the families of those who had been killed, not only to give their testimony but also to arm them and other First Nations communities to hold authorities to account.

It held workshops in First Nations communities so that deaths in custody would never again be hidden from the public.

In the few states that the RCIADIC recommendation that any First Nations person taken into custody be immediately noted to the Aboriginal Legal Service was implemented, the rate of deaths immediately dropped.

After the RCIADIC report was tabled, in April 1991, the CDBR continued to press for full implementation of the recommendations and an investigation of the excluded cases. It also took the issue into international forums.

In the 2000s, the torch was taken upon by other organisations, including the Indigenous Social Justice Association (ISJA), led by Ray Jackson and Raul Bassi, and the Blak Caucus, among others on Gadigal Country/Sydney. Action groups were also started up in other cities.

The case of 17-year-old TJ Hickey, killed in a police pursuit through Redfern in 2004, was taken up strongly by ISJA, and his mother Gail Hickey continues to lead annual marches every February 14 through Redfern to demand justice.

TJ’s impalement sparked a night of “rioting” in the Redfern Block. The community built barricades and kept the cops out of their neighbourhood for some time after his killing.

The Black Lives Matter movement in the United States was a huge boost to the movement here. New layers of mainly young people joined huge marches around the continent.

“I can’t breathe” had a grim resonance here.

Centrality of Black deaths in custody issue

Racism is the systematic expression of historic oppression and a tool of oppression. This is the case not just in Australia but in the US, Apartheid South Africa and apartheid Israel.

It is a central feature of European colonial settler dispossession and genocide everywhere. The dispossessed are branded “sub-human” and the dispossessors superior.

Land theft drives the genocide and then survivors are driven off their traditional lands into concentration camps. They are stripped of dignity, culture and hope, and kept in place by ongoing terror — administered primarily by the police.

This is why the campaign around Black deaths in custody inevitably unpicked the history and led to the 1992 Bringing Them Home report into removal of First Nations children and then the launch of the official Closing the Gap campaign.

The acknowledgement of the historical trauma finally came with Labor Prime Minister Kevin Rudd’s apology 33 years later.

However, the rate of First Nations children being removed from their parents continued to rise from 47.3 for each 1000 in 2019, to 50.3 for each 1000 last year. This is 10 times the rate compared to non-First Nations children and accounts for nearly 24,000 First Nations children (and more than 43% of all children in the system).

The Productivity Commission’s 2025 Report on Government Services showed the child removal system costs $6.6 billion a year, and the child prison system costs more than $1 billion.

This money needs to be spent on addressing the real social issues and on programs to divert the next generation from a course to prison, set in childhood.

This year’s Closing the Gap report found that First Nations children are 27 times more likely to be imprisoned than children in the rest of the population.

This is the grim forward indicator that guarantees that the numbers of First Nations deaths in custody will keep rising.

We need a lot more truth-telling and real action to deliver justice.

[Peter Boyle, a long-term campaigner for First Nations rights, helped the Committee to Defend Black Rights in its early days. He is a member of the Socialist Alliance.]