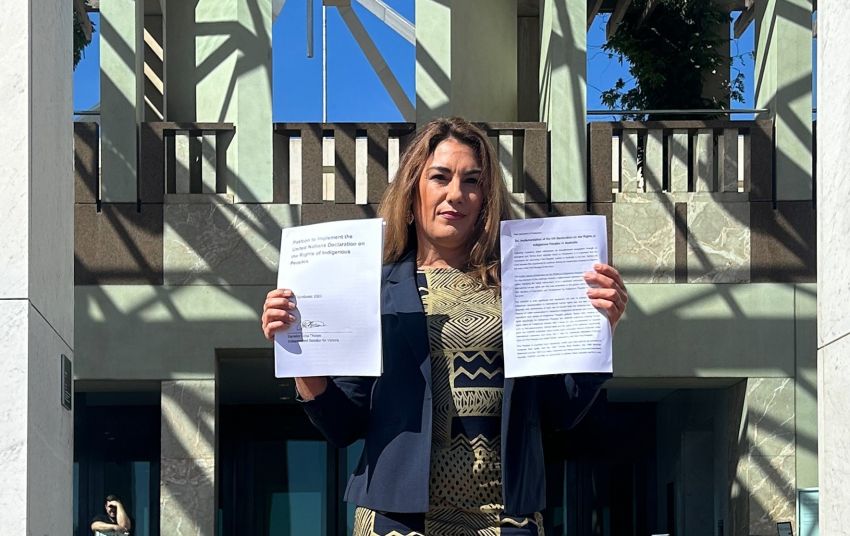

Gunnai Gunditjmara and Djab Wurrung woman Senator Lidia Thorpe introduced a bill in March last year aimed at upholding First Nations peoples’ rights across all law prior to federal Labor being elected.

It finally went to the Senate on December 6, but was voted down by Labor.

Thorpe’s bill proposed a process, reflected in the decades long drafting of the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (UNDRIP), to uphold First Nations peoples’ rights in a system previously denied them; it does not create new rights.

But Labor, which had championed an Indigenous voice to parliament, voted against Thorpe’s bill.

“It is another day in the colony. This is Australia, everybody,” Thorpe said. “This is a government — the so-called progressive Labor government — that waves the Aboriginal flag, wears the Aboriginal earrings and says it’s our friend.

“Yet it denies the rights of Indigenous people in this country. To vote down the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous People is an absolute disgrace.”

First introduced in March 2022 and restored in July of that year after the federal election in May, the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples Bill 2022 created a standalone act that requires the prime minister to produce and roll out “an action plan to achieve the objectives” of the UNDRIP in local law.

The bill maintains the plan be developed in consultation with First Nations peoples and the Australian Human Rights Commission. The measures must address racism, discrimination and prejudice, as well as advance mutual understanding and promote good relations.

The Canadian government released an action plan in June to implement the UNDRIP.

“We survived the massacres, the murders, the rapes, and I’m living proof of that. And I’m so glad I’ve got five years left in this place because I’m going to make your job hell for the next five years,” Thorpe told the Senate. “I will not stop until we get justice in this country for First People.”

Campaign for rights

Ten Senators supported the bill, the including the Greens and Senator David Pocock, while 27 voted against.

Thorpe held a roundtable at Parliament House to address the bipartisan rejection of her bill.

Les Malezer, Gubbi Gubbi and Butchulla man and former UN Permanent Forum on Indigenous Issues expert member, spoke first.

He said the campaign to uphold the rights of Indigenous people began in 1923, when North American Chief Deskaheh called on the League of Nations to recognise the Haudenosaunee nation.

Malezer outlined that there were a number of delegations calling for Indigenous recognition, which included Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander representations, to the British king and the government.

“Fortunately, because of the charter of the UN … the rights of peoples to self-determination has become a principle of rights in the world,” Malezer added.

He said Indigenous peoples have been recognised by the UN and “that has been captured” in the UNDRIP.

Malezer spent decades negotiating the draft of the UNDRIP. He explained that the document doesn’t create any new rights, but serves to uphold the universal human rights of Indigenous peoples as the processes that came before had failed to do so.

He said that the draft declaration was presented in 2006 but Canada, the country coordinating the negotiations, withdrew its support after Australian PM John Howard advised it reject the proposal.

When the UNDRIP was put to the UN General Assembly in September 2007, 144 state parties voted to adopt it. Four settler-colonial nations voted against — Australia, New Zealand, Canada and the United States.

“Let’s not be fooled in Australia. We’ve seen what happened with the referendum. Let’s wake up to the fact that we are dealing with a parliament that is entrenched [in racism],” Malezer said.

Australia ‘especially violent’

“Australia is especially violent when compared amongst the other English-speaking settler colonies,” Mununjali Yugambeh and South Sea Islander Professor Chelsea Watego, author of Another Day in the Colony, told the UNDRIP roundtable.

“We are familiar with terra nullius. We were deemed so subhuman that we lacked any Indigenous political sovereignty. And while we had the Mabo decision, that idea that our Indigenous political sovereignty not be recognised still remains firmly intact, as we saw today.”

The “violence is enacted” against First Peoples via all Australian institutions, she said. The UNDRIP held an opportunity for a way forward, and the current “needs-based approach” taken to First Nations affairs restricts self-determination.

This rights-denying system, Watego said, results in local First Nations people remaining the most incarcerated people on the planet. “The evidence base is clear here: the state is insisting on perpetrating violence on Indigenous peoples.”

An inquiry into Thorpe’s UNDRIP bill tabled its report last month. While it recommended consideration of the value of the declaration articles, and the national plan, the committee did not recommend that the UNDRIP be implemented outright.

Gunaikurnai and Wotjobaluk man Ben Abbatangelo said “over the last two decades, for a plethora of reasons” the focus has shifted from “the inherent rights” and “exclusive status of First Nations peoples that comprises unceded sovereignty”.

He called for “rights-based justice”.

Abbatangelo said he has been contemplating what words should come after the “contemptuous no” that the nation delivered in the Voice referendum. He added that he’s found that the same words, a call for “rights-based justice”, both preceded the national vote and continue on after it.

The journalist further stressed that “from here onwards … we [need to] anchor ourselves and our communities in our inherent rights and our exclusive status as First Nations people.”

We need “the right to be self-determining, autonomous, independent”.

[This article was first published at Sydney Criminal Lawyers.]