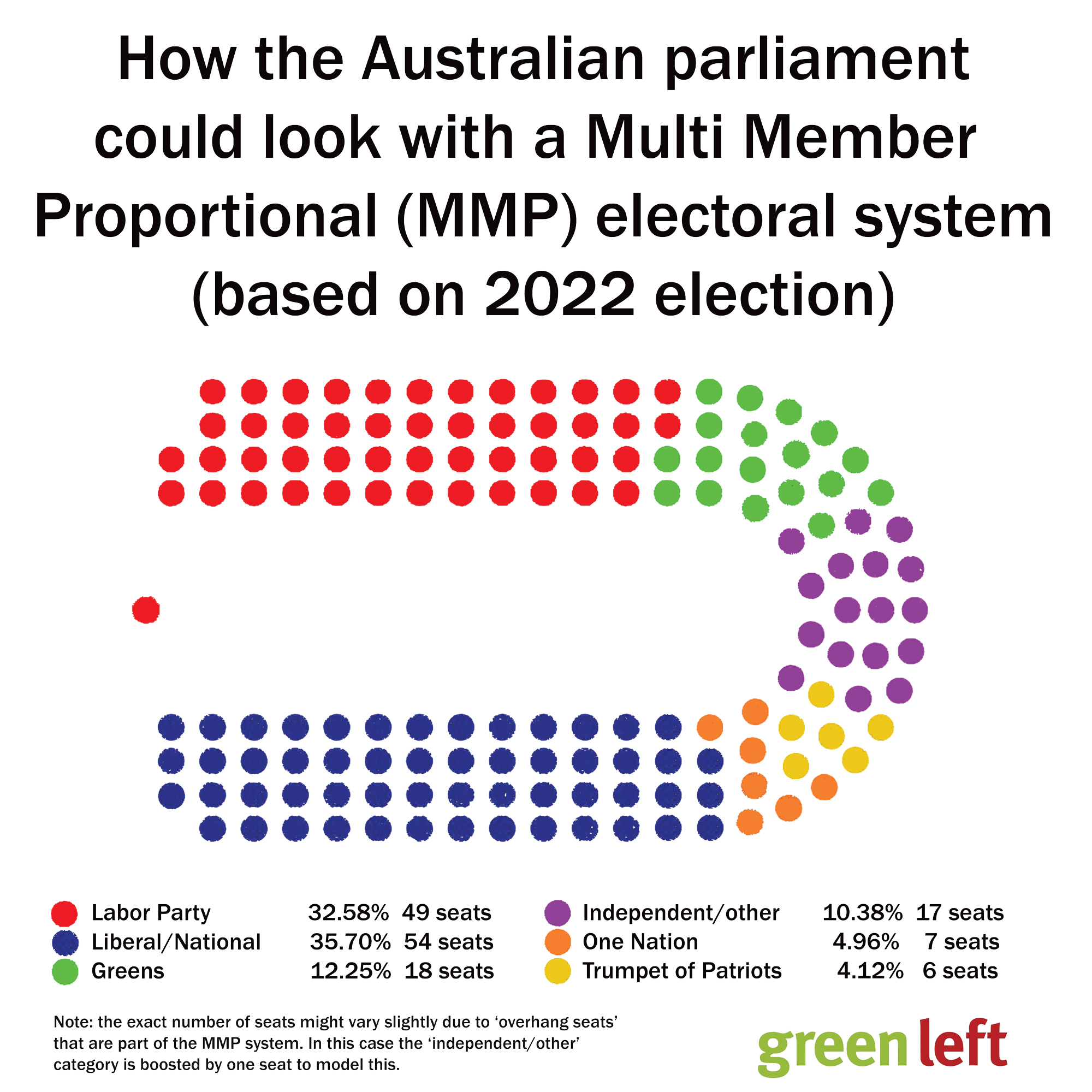

Some pre-election polls are showing a historic tally of seats for Labor. Yet, at the same time, fewer people are voting for the major parties.

How can Labor be set to win big, while its primary vote drops? The answer lies in Australia’s undemocratic voting system, which works to funnel small parties’ preferences to the Coalition and Labor.

Since all seats are geographically based, millions of voters are disenfranchised if the party they voted for does not win in the electorate they live in. It doesn’t need to be this way; other countries use proportional voting systems that ensure the number of MPs elected from each party is broadly representative of how the population voted.

Countries with a proportional voting system usually still have geographically based electorates, but they also have a second part of the ballot where electors vote for the party, or candidate group, of their choice. In a multi or mixed-member proportional (MMP) system, typically half the seats are geographically based and the other half are elected from a “party list”.

A shift to proportional voting in the House of Representatives would be one way to make the system a little more democratic. The existing 150 lower house seats could be merged into 75 “super electorates” and then 75 party list seats could ensure people whose candidate did not win their geographical seat are not disenfranchised.

mmp_zane_alcorn.jpg

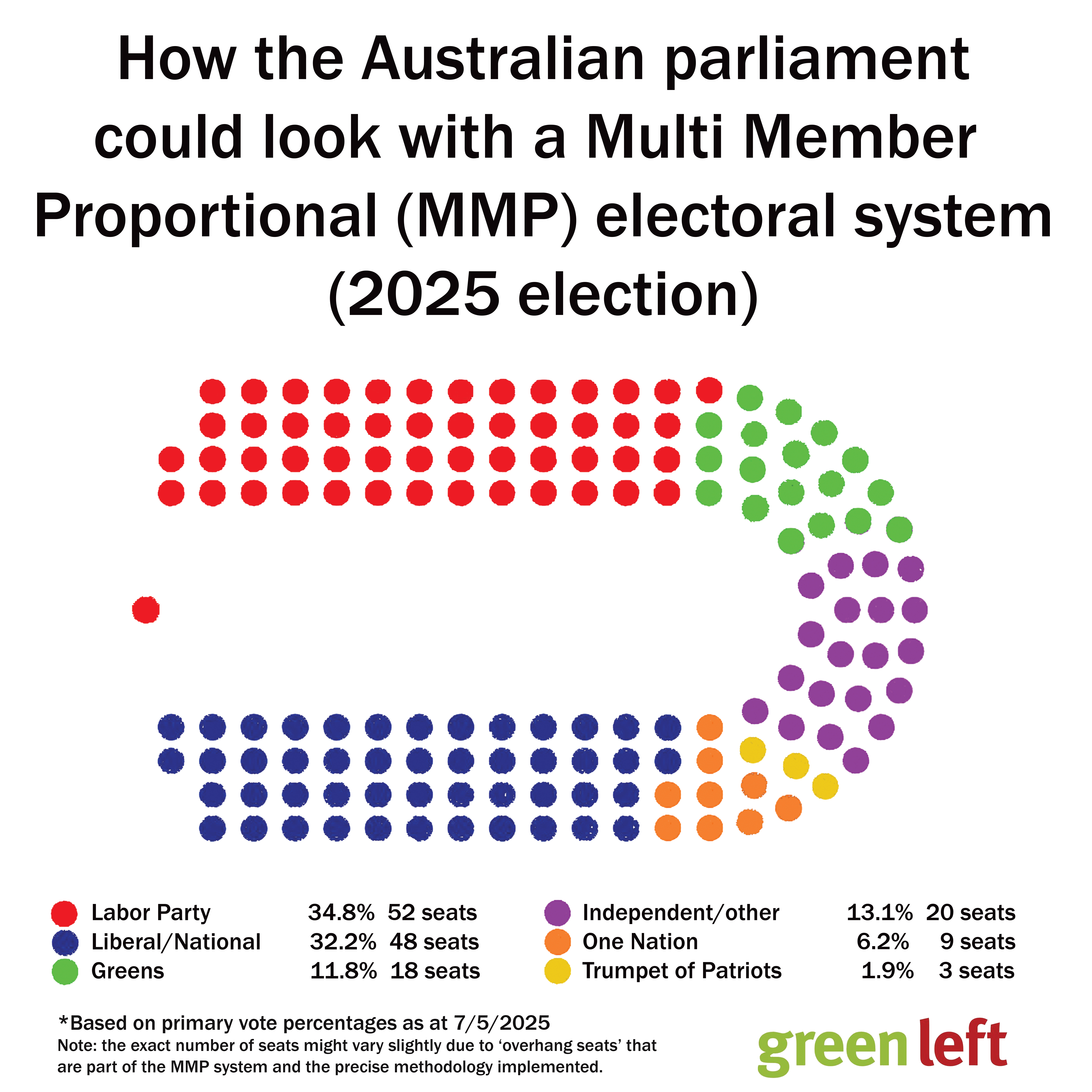

An easy way of illustrating how a a MMP model would look is to convert the results of the 2022 federal election into seats. There are a few factors involved, such as preference distribution in geographically based seats, and “overhang seats”, which allow for parties to “round up” if there is a disparity in the combined votes in geographic based seats, plus the “party list” vote.

In 2022, the Greens won four inner-city seats, but 12.25% of the vote Australia-wide. This equates to about 18 seats out of 150. Under an MMP system, the Greens might have won two of the geographical “super seats” as well as an additional 16 “party list” seats.

Labor won 77 seats in the 2022 federal election. If Australia’s 151 geographically based electorates were merged to form 75 “super seats” Labor might have expected to win 38 or 39. Federal Labor’s primary vote that year was 32.58%, which equates to about 49 seats. So, in this example, Labor would get an additional 10 or 11 “party list” seats to complement the geographically based members who were elected.

Crossbench support will be required for any democratic reform to the parliamentary system. While independents would find it harder to win merged geographic seats under a MMP system, the trade-off would be that people from across the country could vote for an independent group, as opposed to the current situation where only people in the local seat can vote for the candidate. People from anywhere across the country could vote for a Climate 200 slate of candidates, for example.

There is some precedent for progressive independents running on joint tickets under proportional electoral systems, including in Spain.

Double-edged sword?

While a MMP system would lead to an immediate rise in the number of Greens MPs, as well as potentially making it easier for socialists to be elected, the reforms would be a double-edged sword insofar as they would also make it easier for right-wing micro parties.

However, the idea that this would drag politics to the right, as some two-party system defenders suggest, is flawed. The Coalition and Labor have already adopted draconian politics on refugees, for instance, which 30 years ago would be considered far right.

Different countries with proportional voting have different restrictions, or “thresholds”, on parties being elected.

If Australia followed the example of Lesotho, South Africa, Thailand, Namibia or the Netherlands, it could have a “natural” threshold, whereby any candidate or group which gets at least one 150th of the vote (0.67%) is entitled to one of the 151 seats in parliament.

Other countries have a minimum “quota” beneath which parties do not get any seats. These can range from anywhere between 2% to 10% of the vote. Germany and New Zealand, for example, have a 5% threshold. The Irish electoral model is an alternative to MMP, but still delivers a more proportional parliament.

More democratic

While proportional voting may mean more right-wing minor parties (notably One Nation) getting MPs, left and progressive parties would also have more success.

Ultimately, a proportional voting system is far more democratic than what we have now, in which loopholes for those with big money are built into the system.

As the two-party vote continues to fall and the number of small party and independent MPs grow, the Coalition and Labor will be faced with a choice. They can vote together to make the system even more undemocratic, like they did recently with the electoral donation “reforms”, aimed at hobbling the Teals. However, this sort of bipartisan stitch-up will only inflame discontent and drive more people to smaller parties and independents.

The other option for the declining duopoly is to negotiate with the crossbench — which might include reforms to make the parliament more democratic. Either way, the more the two-party vote declines — and the bigger the crossbench becomes — the more pressure on Labor to enact genuine reforms to the electoral system.

mmp-2025-seats-_updated_infographic.jpg