It was a packed night at the Stonewall Inn, a Mafia-controlled gay bar in downtown New York City on June 28, 1969. Stonewall was the only bar in town where gays could dance together, which meant that despite it being dilapidated — there was no running water behind the bar, no fire exits, the toilets overflowed — there was a heavy door charge and the drinks were overpriced.

It was also dangerous. Corrupt New York police received weekly backhanders from the Mafia in return for tip offs about monthly raids that resulted in mass arrests. After police hauled the bar’s patrons and management to the station, the bar was allowed to resume business.

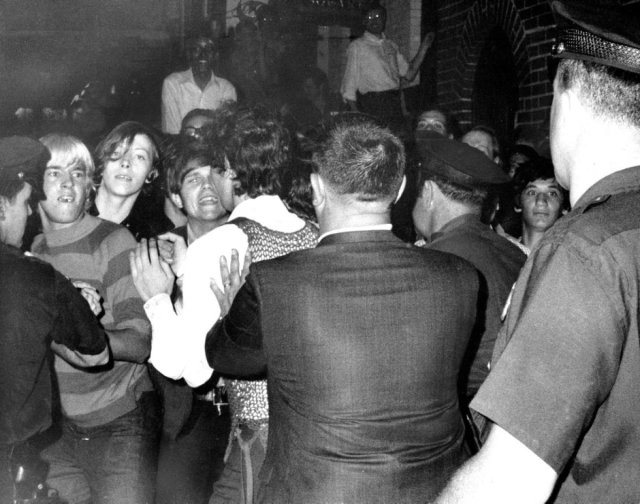

Eight policemen entered the Stonewall that night to deal with the crowd of 200 mostly young and working class gay men. They were expecting the usual routine: lining patrons against the wall, determining whether they were wearing enough items of clothing associated with their sex, then bundling them into police vans to be taken to the station and booked. Often the arrestees were harassed and beaten.

The police had not expected the hostile crowd that began to form outside the bar, heckling the police as they made arrests.

During clothing checks, one officer barked “Move, faggot” at Stormé DeLarverie, a lesbian activist, and shoved her sharply in the back. She turned and punched him in the face, knocking him to the ground. DeLarverie was hauled out of the bar in handcuffs towards the waiting police van. An officer struck her with a baton. DeLarverie turned to the onlooking crowd, bleeding from her head, and shouted: “Why don’t you guys do something?”

What followed was what we know today as the “Stonewall Riots”.

The crowd surged towards the eight police. First, they threw coins to mock the infamous payoffs to police by the bar owners and the rorting of the LGBTIQ community. But coins quickly became larger objects and before they knew it, the police were facing an incensed and advancing mob.

Outnumbered and unprepared, police retreated, with guns drawn, into the now empty bar and barricaded themselves inside. Outside, the crowd freed those in the police vans and turned on the Stonewall Inn with the police trapped inside.

Garbage cans, bottles, rocks and bricks were hurled through the windows of the bar. A parking meter was uprooted and used as a battering ram against the Stonewall’s doors. Some tried to set the bar alight.

Inside, the police called the station for help. It responded by sending the Tactical Police Force, New York’s riot squad.

As word spread, hundreds of LGBT people, street kids and leftists filled the streets, forcing police out of the area for the next five nights.

It was this defiant, political rebellion that today’s pride marches have their roots in.

Rebirth of the movement

This was not the first time gays had fought back, but the 1969 riot marked a rebirth of the movement.

It took place against a backdrop of struggle that was challenging the system from all angles. The anti-war movement had caused mass unrest; African Americans were rioting for civil rights; the second wave of the women’s movement was bubbling over; and workers’ struggles were gaining pace.

The conservative values of the first half of the century were undermined by an explosive combination of liberation movements and a rising tide of working class confidence, which gave the Stonewall riots the momentum to swell into the “Gay Liberation” movement.

That summer there were several smaller incidents of LGBT people fighting back against police violence, leading to the formation of the Gay Liberation Front (GLF) in August.

Leaflets began circulating in Manhattan asking: “Do you think homosexuals are revolting? You bet your sweet ass we are!”.

GLF was established initially to campaign against the owners of the gay bars, who they saw as parasites on the community. But the vision was for broader social and economic change as well.

The GLF was revolutionary and unashamed. It declared: “We identify ourselves with all the oppressed: the Vietnamese struggle, the Third World, the Blacks, the workers, the women … all those oppressed by this rotten, dirty, vile, fucked-up capitalist conspiracy.”

Mardi Gras

Australia’s “Stonewall” came nearly a decade later in 1978, when police attacked the first Sydney Gay and Lesbian Mardi Gras, a festival-march which demanded an end to homophobic “anti-buggery” laws and police violence. It was also a commemoration of the ninth anniversary of the Stonewall riots and a symbol of international solidarity with US activists.

On the morning of June 24, a lesbian-led march of 500 people shocked shoppers as it tore down Oxford Street with resounding chants of “Out of the bars, and into the streets!”. The crowd, seeing that access to Hyde Park was blocked by police, headed towards Kings Cross.

Just before midnight, police moved in to arrest 53 participants in what was described by Campaign, then the only national gay paper and not known for its radicalism, as the “worst police-demonstrator confrontations experienced since the Vietnam protest era”. Inside police cells, arrestees were brutally beaten.

The next morning, the Sydney Morning Herald published the full names and occupations of those arrested, resulting in many people being fired, divorced and estranged from their families and friends.

A campaign was launched to call on the NSW Labor government and the police to drop the charges against the Mardi Gras arrestees. The campaign culminated in a march of more than 2000 people, including gay and lesbian, women’s, left and trade union groups. It was the largest LGBTIQ rights event held in Australia until then.

As demonstrators stopped in front of the Darlinghurst police station to lay wreaths of pansies, police appeared and arrested eleven women and three men.

While the second Mardi Gras went by with no arrests — a victory for the campaign waged in 1978 — a debate raged between those who wanted to retain Mardi Gras as a political protest and those who wanted to make it a celebration of gay and lesbian lifestyles.

Some argued that the politics would need to be put aside to reach broader numbers of people, while activists insisted that owners of commercial gay venues were simply trying to hijack the march for their own profit-making purposes. Lesbian groups argued that it was not enough for Mardi Gras to simply be a celebration, it needed political demands.

One lesbian activist put it this way in Gay Community News: “We chanted slogans against oppressive police attacks and for the revolution. Unfortunately we were drowned out by the music truck. When we asked for the music to be turned down we were told by the male marshal that ‘this is the music truck’.

“I asked myself what the purpose of the Mardi Gras is. Isn’t it the commemoration of a brutal attack on American gays? Didn’t police attack lesbians and gay men in Sydney two years ago? Aren’t gays still living in fear of brutality, conviction and harassment every day? But let the music play on …

“Will the Stonewall commemoration become a rival to Moomba, or are we going to use it as a chance for political comment and power by sheer numbers and solidarity?”

The shift from radical demands to a commercialised event was marked by the change in leadership, from the Gay Solidarity Group, a radical liberation organisation, to an appointed “Task Group” whose emphasis was on making Mardi Gras a street party, without any particular reference to politics.

Mardi Gras was also moved to March, away from the anniversary of Stonewall.

By 1982 the organising committee was declaring that they were “keen to have maximum commercial participation”. Mardi Gras quickly became such a financial success that it prompted much animosity between activists and gay business operators over the parade route.

Reviving radical roots

Mardi Gras has grown exponentially since the first march. This year 12,200 people are set to participate in the parade and 300,000 are expected to watch.

But as the 78-er militants who fought to maintain the defiant demands of the first Mardi Gras had warned, the increasing corporatisation of the event has lead to the watering down of its once-radical politics.

Today, Mardi Gras’ success is measured in financial, rather than political, terms. The political history of Mardi Gras, let alone the Stonewall Riots, has been scrubbed from the parade — in its place is the glitter-encrusted message that LGBT people are “just like everyone else”.

Yet Mardi Gras is rooted in a movement against the political establishment and the parasitic owners of the “pink economy” and their collaboration with police — the very people who today are the organisers of the event.

The most virulent opponents of the first Mardi Gras have been seamlessly incorporated into the now apolitical event.

The NSW police march in the parade they once violently attacked; the Sydney Morning Herald has published a satirical “Mardi Gras Survival Guide” despite having torn apart the lives of the march’s first participants; the Labor Party marches alongside the 78ers they hung out to dry; and the Liberal Party smiles and waves while still denying marriage equality.

Rather than fighting for our rights, we are asked to settle for a party.

But many of us still refuse. The organisers frequently thwart attempts to politicise the parade. Last year, they overturned a motion in Mardi Gras’ annual general meeting to ban Prime Minister Malcolm Turnbull from the parade and threatening to expel the “No Pride in Detention” float for chanting pro-refugee slogans near Labor leader Bill Shorten.

For Mardi Gras to have a meaningful impact on social change, it must revive the demands it once championed: an end to police violence and corporate profiteering, and equal rights now.

The first “pride” march was a riot but despite being a long way from sexual and gender liberation, Mardi Gras seems to signal that the fight is over. Homophobia still reigns in the political establishment.

Within the parade and outside of it, we must reinject the radicalism that birthed our moment.

The rioters were right. Unshackling ourselves from shame and stigma and winning equal rights will demand an overhaul of our current political system.

Revolting? You bet your sweet arse we are.

[Mia Sanders is a national co-convener of Resistance: Young Socialist Alliance.]

Like the article? Subscribe to Green Left now! You can also like us on Facebook and follow us on Twitter.