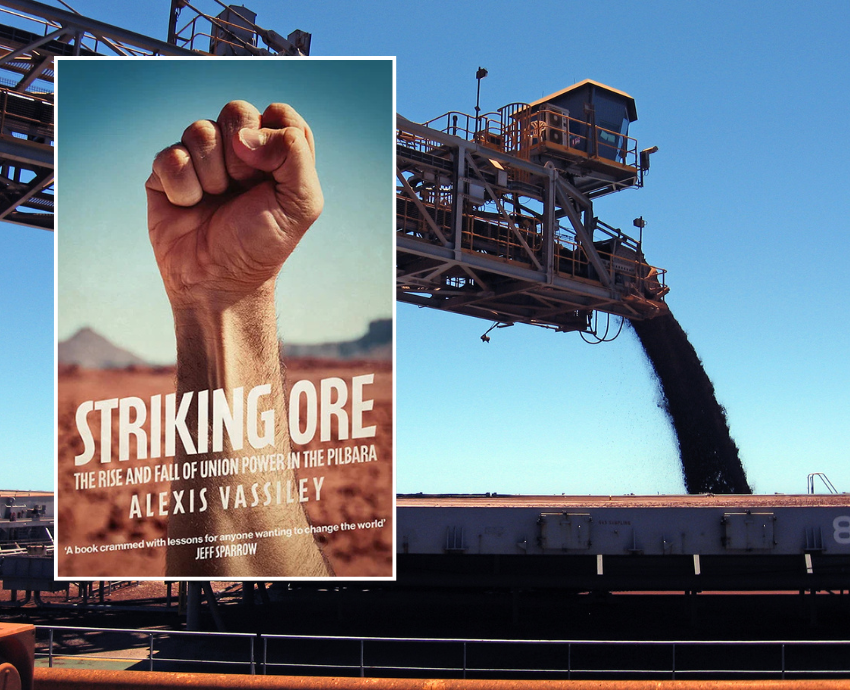

Striking Ore: The Rise and Fall of Union Power in the Pilbara

By Alexis Vassiley

Melbourne: Monash University Publishing, 2025

“We had industrial muscle and we used it. There was no fear,” said Randall Grant in 2018, of his time as an Australian Worker’s Union (AWU) shop steward at Hammersley Iron’s Dampier port in the 1970s.

In 2019, another union organiser Jeff Carig said about conditions under Rio Tinto in the Pilbara that “[The company says] it’s always ‘safety before production’. Someone on the ground will tell you a 100% it’s always about production over safety.”

These quotes show the contrast between the conditions in the iron ore industry in the Pilbara region in Western Australia in 1970s — when union power was at its peak — and since that power collapsed in the 1980s.

Trade unionist, academic and socialist activist Alexis Vassiley tracks this rise and fall in his book, Striking Ore: The Rise and Fall of Union Power in the Pilbara.

Prior to the growth of the iron ore industry in 1960s, the Pilbara’s main industries were pearling and the pastoral industry, which depended on unpaid Aboriginal labour. Eight hundred Aboriginal stockmen went on strike on May 1, 1946, which communist and union solidarity — including a 1949 Seaman’s Union ban on the loading of Pilbara wool — enabled to be won in 1949. However, many of the workers never went back to work, meaning the strike never officially ended.

From 1965–72, the Electrical Trades Union and the AWU sent organisers to the Pilbara to seek out rank-and-file union members working in the iron ore industry who were willing to take militant industrial action and to develop grassroots networks of shop stewards and combined union committees.

Due to the poor working conditions on these mine sites, workers repeatedly took strike action — many of them unsanctioned wildcat actions — between 1967 and 1969.

As a result, the bosses were forced to grant limited recognition to shop stewards in the 1969 Iron Ore Industry Award.

Pilbara unionists also played a crucial role in solidarity with the nationwide strikes in solidarity with tramways union leader Clarrie O’Shea in 1969.

Following more strikes in 1970, workers gained significant breakthroughs in wages and conditions. In the second part of Striking Ore, Vassiley describes the peak of union power in the Pilbara from 1973–86, when workers gained significant control over the industry and the towns they lived and worked in.

The Pilbara become synonymous with militancy and strikes in the 1970s, leading to newspaper headlines such as “Industrial trouble in the Pilbara”. By this time, key union infrastructure, such as shop stewards networks and combined union committees, enabled workers to often bypass the Perth-based union bureaucracy and curbed the worst excesses of management authoritarianism.

Key strikes in this period were a three-week strike at Goldsworthy in 1974, a five-week strike of Mount Newman train drivers in November and December 1976 and a ten-week strike at Hammersley Iron in 1979, involving all the industry unions. This last strike took place amid a nationwide strike wave in 1979–81.

As well as frequently striking for better pay and conditions, Pilbara unionists also struck to improve the living conditions and amenities in the towns they lived in and took significant action in solidarity with the Noonkanbah Aboriginal community, who sought to prevent oil drilling on their land in 1979–80.

Workers in the towns of Shay Gap and Tom Price set up cooperatives in the form of worker-owned supermarkets. The workers’ ability to improve their amenities made these places better communities. In the book, AWU shop steward Herry Hoskins recounts how in the town of Paraburdoo he played sport every night of the week, saying “The union was a big part of my life. They were some of the best years of my life.”

However, a key weakness Vassiley notes was the lack of political consciousness among union members. Very few were Australian Labor Party members, even less belonged to the Communist Party of Australia (CPA) or had even heard of other socialist groups to the left of the CPA. This would cause problems when the Pilbara unionists faced attacks led by the New Right in the 1980s.

The decline of union power in the Pilbara began in June 1986, when mining company Peko-Wallsend’s new CEO — who had links to the New Right, including future John Howard government treasurer Peter Costello — terminated longstanding union agreements at Robe River mine.

After winning the 1983 federal election, the Bob Hawke Labor government implemented the class-collaborationist Prices and Income Accord it had signed with the Australian Council of Trade Unions (ACTU) in 1982. The accord required the union bureaucracy to police their members to prevent industrial action.

Most mining companies disagreed with Peko-Wallsend’s aggressive anti-union tactics, instead being content to maintain a more conciliatory approach to the unions. Many unionist activists argued that the company could have been defeated if the unions had taken militant strike action, especially after it locked out 1160 workers in August 1986.

The union bureaucracy remained committed to a strategy of lobbying the Western Australian Industrial Relations Commission and the WA and federal Labor governments. Limited strike action taken between December 1986 and January 1987 came too late to prevent defeat, with the ACTU striking a deal with Peko-Wallsend that stripped the unions of their power at Robe River.

In contrast to Robe River, unionists were able to defeat attempts by management to de-unionise the Mount Newman mine in 1988 (now owned by BHP). Workers there struck for three weeks, defying the WA Industrial Relations Commission. However, their victory only temporally halted the Pilbara’s de-unionisation, with mining companies finally defeating the unions at Hammersley in 1992–93 and Mount Newman in 1999.

Today, the iron-ore industry makes huge profits, while workers endure insecure jobs and 12-hour shifts. “Fly-in fly-out” workers experience mental distress, and sexual harassment is rife.

Workers face an authoritarian management and union density is only 3–5%. Organiser Jeff Carig said of Rio Tinto that it “installed a culture of fear around joining unions … If you joined a union, you were targeted and then you were terminated.”

Since 2013, the Western Mine Workers Alliance has been attempting to rebuild union power in the Pilbara in the face of a strongly anti-union industry. Train drivers at BHP’s Pilbara operations finally signed an enterprise agreement (EA) last year, after a seven-year struggle. They now earn up to $225,000 a year, 15% more than train drivers at Gina Rinehart’s Roy Hill mine — where they don’t have an EA.

Despite this success, the union movement still faces immense challenges, with mining companies fiercely resisting attempts to re-unionise the Pilbara. In addition, the corporate media runs hysterical anti-union headlines, such as the April 24 West Australian newspaper, which warned: “Radicals Backdoor into the Pilbara” in response to union organising efforts.

The decline of the union movement in the Pilbara mines reflects a wider trend in Australian unions, from the Hawke-Keating Accord years to the election of Howard’s Coalition government in 1996, to today, where only one in eight workers are members of a trade union and only one in 20 workers under 25 are union members.

Today, strike days are at record lows, and in workplaces with a union presence, delegate and shop steward structures are weak or non-existent. Union strength must be rebuilt, to tackle inequality, insecure work and wage theft.

Through his interviews with union activists and archival research, Vassiley shows that militant rank-and-file organising, like we saw in the Pilbara in the 1970s and ’80s, is needed.

Learning the lessons of the militant struggles by the Pilbara unionists is also necessary, and Striking Ore is an invaluable resource.