King Abdullah bin Abdulaziz of Saudi Arabia has died at the age of 90. Abdullah was one of the world’s most powerful men and a key US ally in the region, controlling a fifth of the known global petroleum reserves.

In a statement, President Barack Obama praised Abdullah for his “steadfast and passionate belief in the importance of the US-Saudi relationship as a force for stability and security in the Middle East and beyond.”

However in 2010, WikiLeaks published US diplomatic cables that identified Saudi Arabia as the world’s largest source of funds for Islamist militant groups. Abdullah also sent tanks to help squash pro-democracy uprisings in neighbouring Bahrain.

Saudi Arabia recently came under criticism for its treatment of imprisoned blogger Raif Badawi, who was sentenced to 10 years in prison and 1000 lashes to be carried out at a rate of 50 a week for charges including insulting Islam.

Abdullah’s half-brother, Crown Prince Salman, has now assumed the throne. Democracy Now! spoke to Toby Jones, director of Middle Eastern studies at Rutgers University and the author of Desert Kingdom: How Oil and Water Forged Modern Saudi Arabia. It is abridged from DemocracyNow.org.

What does Abdullah’s death represent?

Abdullah’s death marks a transition. He came to power formally in 2005, celebrated as a potential reformer, as somebody who would modernise and lead the kingdom forward.

But it turns out he’s largely failed on every one of those measures. He has turned the clock back in terms of inciting sectarianism at home and supporting the forces of radicalism abroad.

He saw the Arab Spring, the uprising in Syria, as an opportunity to challenge both Iran and Assad’s power there, knowing full well what the possibilities of blowback and the rise of a new regional terrorism might be.

His regime supported instability in Yemen. It crushed pro-democracy forces in Bahrain.

Abdullah is somebody who was well liked in the West. But his record is one that’s consistent with his predecessors: It’s at odds with democracy and human rights.

What is the state of human rights and democracy in the Saudi kingdom?

It is as bad as it’s ever been. Its prisons are full of political prisoners — they have been for quite a long time.

There’s been a steady string of arrests over the past few years. We pay attention now because of the crude, terrible nature of public beheadings and the medieval punishment of lashing people for speaking their minds. But this has been going on for quite a long time.

It is worth remembering that early last decade, Abdullah, as crown prince, became a darling of the reform lobby and of what we might call the moderate wing of Saudi Arabia’s political society.

He was seen as a reformer. He was embraced by a broad cross-section of people who believed he was going to spearhead a period of liberal opening.

But when he saw opportunities to crush and push back against those who might challenge Saudi political primacy, he did. And he did so as crudely as any of his predecessors. He was not a benevolent dictator. He was a dictator.

Can you talk about the man who will succeed him, King Salman?

Salman is at least 79, if not older. It is likely that his reign will be a short one and that there are powers behind the throne that will make sure that the interests of the royal family will be protected.

The family protects itself. There is an arrangement likely in place in which the king is the first among equals; nobody can act too radically or too out of step with the interests of the family more broadly.

So Salman’s reign will be probably very consistent and similar to that of Abdullah’s. He’ll be a figurehead. He will likely wield some kind of influence, as will those who are closest to him, as will his successor — the current crown prince Muqrin, who is probably about a decade younger.

The royal family’s interests are in protecting themselves first, their privileges second, and making sure that there are limited challenges to their authority.

What about the role of the Saudi family or the Saudi elite in the continued financing of jihadists around the world?

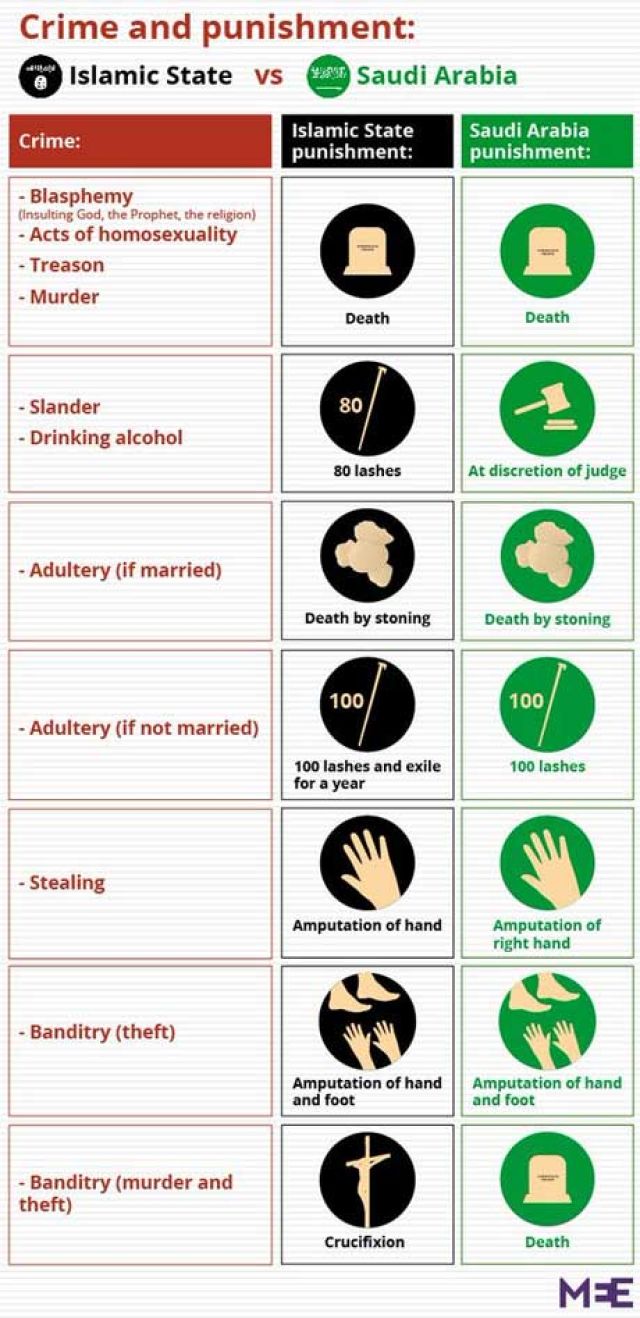

Saudi Arabia is a wellhead for a certain kind of ideological production. There is a lot of talk about Wahhabism and the similarities between what is the official orthodoxy of the Saudi state and groups like al-Qaeda, ISIS and others. I think those ideological connections matter.

There are certainly operators on the ground. There is support within Saudi mosques for these kinds of networks. The Saudi state, however, is in a more difficult position.

I think the Saudi rulers view the regional political landscape through the lens of good, old-fashioned geopolitics. They see Iran as a rival. They see Assad as a pawn in that game.

And they understand that they have a kind of limited playbook, that there are kind of natural alliances with which they can forge mutual interests and cooperation. The Islamists happen to be among those.

But I don’t think the royal family is necessarily an ideological actor in the same way that some of the clerics in Saudi Arabia are. They reach out to these networks because they have to. They’re dealt a certain hand and they play the game the best they can.

But this is a dangerous proposition — it was in Afghanistan in the 1980s and in Iraq after 2003 — where the Saudis forge alliances, or allow some on the margins of the government to fund and support networks, that are also dangerous to the regime itself.

That’s why they are building a big fence on their border with Iraq. On the one hand, they’d like to see ISIS do damage in Syria, but they don’t want to see it come home.

Over the long term, this is an unsustainable, untenable proposition. The Saudis are eventually going to have to make a deal. They’re going to have to reckon with the blowback from Syria and Iraq. They’d like to postpone it as long as possible, but it’s likely to be inevitable.

What about the relationship between Saudi Arabia and the United States?

This is a long-standing and complicated one. It’s often framed through the lens of security and stability. And that certainly matters from the perspective of both Saudi and US policymakers.

If we peel back the layers of what this means, though, it’s not always clear. It’s not as though the Saudis have any power to really shape the region or defend their interests militarily.

They’re largely dependent on the US for security assurances. The US has happily projected its military power into the Persian Gulf since at least the early 1970s.

I think what this really comes down to is that the Saudis are the world’s most important oil producer. For that reason, they’ve been in the US political orbit since at least the late 1930s.

But oil wealth also does a lot of other things. It gets recycled to the US economy, especially by the purchase of weapons. Our relationship is not just about providing security for oil — it’s about maintaining a certain kind of strategic and economic relationship that profits both sides.

Like the article? Subscribe to Green Left now! You can also like us on Facebook and follow us on Twitter.