After a week of counting by the United States National Labor Relations Board (NLRB), a majority of those casting a postal vote at an Amazon warehouse in Bessemer, Alabama rejected a unionisation effort by the Retail, Warehouse and Department Store Union (RWDSU).

Workers voted 1798 to 738 against joining the RWDSU. The turnout was just under 55% (3215) out of a workforce of 5876.

It was the closest Amazon workers in the United States had come to unionising . Alabama is a Deep South, “right-to-work” state, which bans unions from compelling workers to join. Solidarity strikes are also illegal.

RWDSU president Stuart Appelbaum said workers voted against forming a union out of fear they might lose their jobs -- a common tactic employed by union-busting employers.

“Of course, we’re going to be disappointed and angry about the way this election turned out,” Bessemer warehouse worker Emmet Ashford told a media conference.

The RWDSU immediately lodged an appeal of the outcome with the NLRB, alleging intimidation and unfair practices by Amazon during the campaign.

Ashford said despite the loss, Amazon workers are proud they are inspiring workers at other warehouses to consider unionising.

“Our time will come around again.”

Why the no vote won

The majority African American workforce made its decision on a practical basis. They were not hostile to the idea of a union. They were just not convinced.

Many workers who voted "No" said they didn’t see how the union would improve their wages and working conditions.

“Amazon is the only job I know where they pay your health insurance from Day 1,” one worker told the New York Times. She said she had been turned off by how organisers tried to cast the union drive as an extension of the Black Lives Matter movement because most of the workers are Black.

“This was not an African-American issue,” said Stokes, who is Black. “I feel you can work there comfortably without being harassed.”

The vote count was live-streamed online. The NLRB reviewed and certified ballots behind closed doors, setting aside 505 contested ballots, which were not included in the final tally. The union said the majority were contested by Amazon. The NLRB determined there weren’t enough to affect the election result.

While it is too soon to say what impact the defeat at Bessemer will have on future organising at Amazon, it is a big setback.

In the 1990s, a similar effort occurred at retail giant Walmart, the largest employer in the country.

Walmart’s workforce of 1.4 million remains non-union. It used sophisticated union-busting tactics, combined with strong legal actions undermining weak labour laws.

Amazon’s strategy added a “progressive” twist, donating money to Black Lives Matter organisations and civil rights groups such as the NAACP.

Amazon also supports raising the national minimum wage to $15 an hour, twice what it currently pays its warehouse workers.

Union responses

In response to the Bessemer defeat, many union leaders said they would step up efforts to highlight and resist the company’s business and industrial practices, rather than seek elections at individual job sites, as in Bessemer.

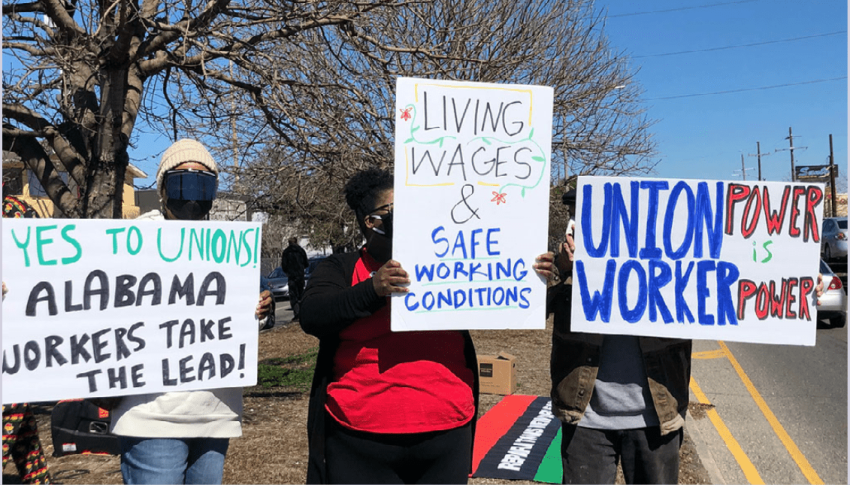

This approach includes walkouts, protests and public relations campaigns that draw attention to Amazon’s leverage over its customers and competitors.

One Teamsters union official said unions must relook at what is possible in today’s anti-union climate.

“We’re focused on building a new type of labour movement, where we don’t rely on the election process to raise standards,” said Jesse Case, secretary-treasurer of a Teamsters branch in Iowa that is seeking to rally the state’s Amazon drivers and warehouse workers to pressure the company.

It includes focusing on pro-union legislation, such as the Protecting the Right to Organize Act (PRO Act), adopted by the House of Representatives and awaiting a vote in the Senate.

If passed, this law would allow unions to overrule so-called “right to work” laws, ban “captive audience” meetings by employers — which Amazon management forced its workers to go to — and restrict employer interference in union elections. It would also legalise solidarity strikes.

Had this law been in place, it certainly would have helped in the Bessemer ballot. But there is a danger that union leaders are over-emphasising the PRO Act as a panacea.

When Barack Obama was president, the Democrats controlled both the House and Senate, yet failed to pass similar legislation. Organised labour continued its strong support for the Democrats despite this failure. Many rank and file workers, especially white workers, turned to conservative Republicans and Donald Trump as an alternative.

A repeat of the Walmart-style campaign as a new union strategy cannot succeed.

While Walmart has made some improvements to wages and conditions, they still lag far behind their union-organised competitors.

Labour historian Nelson Lichtenstein told the NYT: “Walmart would send teams to swamp the stores to work against a union. They are good at it.”

Amazon took Walmart’s playbook and applied it ruthlessly.

Lessons of the 1934 union upsurge

It is important, instead, to learn from one of the greatest organising periods in the US, in the 1930s. After the 1929 Stock Market Crash and suffering of the Great Depression, unions were defeated, and membership sharply declined. By 1933, union membership was almost half what it was a decade earlier.

This changed in 1934. Three mass strikes were won by combining internal plant organising with community organizing -- in Minneapolis, Minnesota, led by truck drivers, in San Francisco, California, organised by wharfies and in Toledo, Ohio, led by car parts workers.

The 1933 Industrial Recovery Act gave workers the right to organise and collectively bargain, but it did not mean employers did so. Workers had to strike to get an agreement.

The workers’ successes inspired confidence across the country.

The strike campaigns included forming women’s strike support groups and beating back the employers’ private goons.

Each strike was consciously led by radicals and leaders of the socialist and communist movement. They built a union drive that went beyond traditional plant organising or full-time union staff.

Those victories led Franklin Roosevelt’s government to pass the Wagner Act of 1935 that guaranteed the right of workers to organize, outlined a legal framework for union-management relations and provided a framework for collective bargaining.

Until WWII, the labour movement was at its strongest point (except in the Jim Crow segregated South, where Blacks had few rights and all-white union branches dominated).

Following World War II, a huge strike wave broke out, in 1945-46, to recover losses due to the war effort. In response, the Republican-controlled Congress adopted new laws to weaken the Wagner Act.

The 1947 Taft-Hartley Act was a big blow to union organising, especially in the segregated South. The failure to take on racism in the South became the union movement’s Achilles heel.

The act prohibited jurisdictional strikes, wildcat strikes, solidarity or political strikes, secondary boycotts, secondary mass picketing and closed shops.

The Taft-Hartley Act also allowed states to pass so-called "right-to-work" laws banning closed shops. Enacted during the early stages of the Cold War, it also required union officers to sign affidavits that they were not members of a communist organisation.

In the segregated South, where African Americans had few rights, the unions refused to fight racist laws. Black-white working class solidarity was nearly impossible, even around bread-and-butter economic issues.

In the 1960s, union gains mainly occurred in the public sector. Victories were still possible in basic industry, but technological advances by the 1980s dramatically raised productivity and permanently reduced union membership and power in coal mining, steel and car manufacturing.

The same happened in the railway and airline industries

In the airline industry, where I worked for many years, the unions all sought significantly more than 50% worker support before seeking elections. Even though the airlines used union-busting tactics, the unions already had a majority of workers potentially ready to vote union.

Organising on the job and labor laws

On-the-job organising alone is not sufficient to win. Community support, including home visits and calls, is essential to enable workers to take on their employer. The Amazon workers received strong support from worker and community coalitions, yet in-house calls and visits were limited.

The labour movement continues to rely on friendly politicians or hope that anti-labour laws are overturned. However, it requires a combination of traditional union organising with mass public pressure to win.

As Appelbaum said, the Bessemer vote results “demonstrate the powerful impact of employer intimidation and interference”.

The union has email evidence, obtained under Freedom of Information that alleges Amazon pressured the US Postal Service to install a mailbox outside the Bessemer warehouse. The union says that action amounts to cheating and violates labour law. Evaluating the allegations could take several months.

Some pro-labour academics said the defeat reflects historical weaknesses in labour law, the difficulty of uniting workers in a weakened economy, and the political challenge of checking corporations that espouse progressive values even as they aggressively oppose unions.

Most labour laws are tilted toward employers and should be repealed, such as the infamous Taft-Hartley Act, which outlaws discrimination against non-union members by union hiring halls, and “closed shops”.

Unions made repeal of Taft-Hartley and other anti-labour laws a demand for decades, but unfortunately with little muscle behind it. Their “allies” in the Democratic Party have refused to act, even when they held majorities in all three branches of government.

Workers will continue fight

Amazon’s claim that is progressive and believes in the dignity of its employees is “mythology”, said UCLA historian Robin D G Kelley in the Los Angeles Times. “It’s one of the worst workplaces in the country, just in terms of physical brutality on the body.”

But the fight at Amazon marks a new phase in industrial relations in the tech industry. “They can’t put the genie back in the bottle,” said Kelley.

Tech giants, including Facebook, Apple, Microsoft, Google and Amazon, fear their workers unionising. They are the new industrial union busters of the 21st century.

The defeat at Bessemer is not the end. It is a setback, but can be turned around by returning to the lessons of previous union upsurges.

The intimidation and fear, and likely illegal actions of Amazon that prevented a majority voting Yes, will be seen as a temporary setback, as working conditions worsen and union organisers are sacked or pushed out.

Amazon has been unionised in other countries. The RWDSU leadership and other labor groups are determined to join the international movement to bring Amazon to the collective bargaining table.

[Malik Miah worked more than two decades as a mechanic at United Airlines in San Francisco and was one of the chief contract negotiators for the Aircraft Mechanics Fraternal Association (AMFA) when the company was in bankruptcy. He has been a shop steward for many other unions, including the Machinists and Teamsters.]