Once the count had finished for the Spanish Basque Country’s (Euskadi) April 21 election for its 75-seat regional parliament, not much seemed to have changed.

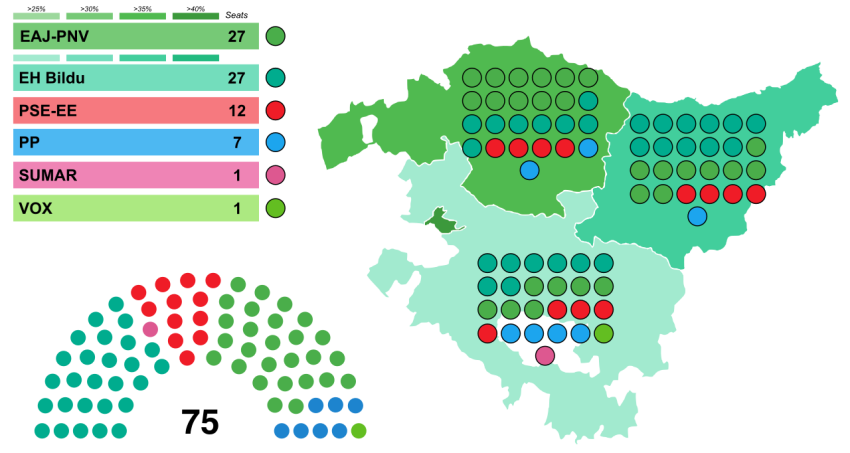

The Basque Nationalist Party (PNV, 27 seats) will still form government, as it nearly always has since the 1980 restoration of parliament after the Francisco Franco dictatorship ended.

The left-nationalist electoral alliance EH Bildu — now equal with the PNV on 27 seats — will continue to be the main opposition force.

With 12 seats, the Socialist Party of Euskadi (PSE), the regional franchise of the Spanish Socialist Workers Party (PSOE), will continue to give support to the PNV whenever needed to keep EH Bildu’s hands off any levers of power. Likewise for the People’s Party of Euskadi (PPE), the local branch of the all-Spanish People’s Party (PP), with seven seats.

Last year, it was a PNV-PSE-PPE alliance that kept EH Bildu from assuming the mayoralty of the Euskadi capital Gasteiz (Vitoria) after the left-nationalist force came first in the May 28 municipal elections.

A similar deal will now produce a PNV-PSE 39-seat majority coalition administration.

However, despite these appearances of continuity, any impression that normal operations can now resume is quite misleading. This is because the election result leaves the incoming PNV-PSE administration more exposed than ever to EH Bildu initiatives on social issues and Basque national rights.

EH Bildu's increased political and social weight will raise tensions within a PNV-PSE government with growing vulnerability for both parts: for the PSE if it accepts PNV neoliberal social policies and for the PNV if it keeps surrendering to the PSOE’s Spanish centralist rejection of a Basque right to decide.

Threat held off

The rise of EH Bildu in the run-up to this election threatened conservative nationalist hegemony as never before, with the PNV having to pull out all stops to defend its citadel.

Its defence operation began with the party machine dropping three-term PNV premier Íñigo Urkullu as lead candidate. He was replaced by Imanol Pradales, a “freshface” marked by scandal for having shares in construction companies contracted by the Biscay area regional government in which he was minister.

EH Bildu carried out a parallel move, with Basque left nationalism’s long-running lead candidate Arnaldo Otegi voluntarily stepping down in favour of the party’s program director, engineer and university lecturer Pello Otxandiano.

The PNV operation against EH Bildu was a huge scare campaign aimed at getting the conservative voter, possibly complacent about another repeat victory, out on election day.

Such was PNV nervousness that Imanol Pradales lied that EH Bildu policy would see all Basques paying €5000 a year extra in tax. By the last week of the campaign the PNV was repeating PP and PSOE demands that EH Bildu seek forgiveness for the damage caused by the Basque separatist group ETA.

Results

The result of this heightened temperature was that the participation rate, compared to the previous election in 2020, jumped by a record 11.7% — from 911,000 then, to 1.06 million on April 21.

The turn out meant that all parties’ absolute vote rose. The exceptions were the all-Spanish left forces Sumar and Podemos, which stood on a single platform as Unidas Podemos (UP) in 2020.

The PNV vote rose by 36,000, the PSE by 28,000, the PPE by 37,000, and the xenophobic Vox by 3800. But easily the biggest rise was for EH Bildu: 93,000 (from 27.8% to 32.5%).

Despite this, the PNV maintained its position as winner on votes (35.2%) because it held onto its traditional stronghold in Bizkaia province, winning 11 of that constituency’s 25 seats to EH Bildu’s 8.

EH Bildu came in first in Euskadi’s other two provinces, for the first time beating the PNV by 8 seats to 7 in Araba and 11 seats to 9 in Gipuskoa.

The three provinces each elect 25 members to the Basque parliament, irrespective of population. It takes about 36,000 votes to elect an MP in Biskaia, 22,000 in Gipuskoa and 10,000 in Áraba.

What were the sources of EH Bildu’s vote surge? Detailed analysis remains to be done, but according to the last opinion poll before the election (by 40dB), 6% of non-voters in 2020 (about 50,000) would vote EH Bildu at this poll, followed by 9% of PNV voters (about 31,000), 27% of Unidas Podemos (UP) voters (about 20,000) and 4% of PSE voters (about 5000).

Reasons for a surge

EH Bildu’s power of attraction had two main sources: it was most closely associated with Euskadi’s ongoing social and national struggles and is seen to be offering credible concrete solutions to the problems generating them.

Its approach was to present its progam not as a list of vote-grabbing promises, but as a road map for action if it won government. It said: “Have no doubt that we will do everything within our power to realise the proposals brought together in these pages.”

At the centre of the program are proposals to revive and modernise Euskadi’s public services — particularly health, education, housing and aged care.

The COVID-19 pandemic exposed the holes in the Basque public health system, which the previous government tried to solve with increasing privatisation — protests on March 24 brought thousands onto the streets against this policy.

The PNV has also been trying to sabotage the Housing Law adopted last year by the central PSOE government, with the support of EH Bildu. This was aimed at curbing market deregulation that benefits big landlords and allowing regional governments to limit rent rises in areas of “housing stress”.

The PNV voted against the law in the Spanish congress, and then filed an appeal of unconstitutionality to the Constitutional Court on the grounds that it violates regional government rights.

EH Bildu proposals

By contrast, the EH Bildu proposal committed to applying rent controls, expanding public and community housing — through taking over empty housing and new construction — and tightening eviction laws with a view to eliminating evictions altogether.

Against labour market casualisation and rising poverty, the EH Bildu program proposed a minimum wage of €1400 euros, a 32-hour working week with no reduction in pay, the comprehensive reinforcement of occupational health and safety inspections, a fight against the gender wage gap, the signing of the Pact for the Basque Framework for Labour Relations and Social Protection and support for a €1080 minimum monthly income in line with pensioner demands.

In addition, EH Bildu’s work in local government, besides being completely free of the corruption associated with the traditional parties, is based on permanent collaboration with social movements, citizens associations and trade unions.

This approach has provided living proof at the local level that the organisation’s promise to do everything possible to realise commitments isn’t just hot air.

On the issue of the Basque right to self-determination, EH Bildu is presently operating to implement the 2018 parliamentary resolution “Agreed Bases for Updating Euskadi’s Self-Government”, negotiated with the PNV.

However, while the left nationalists see this updating of Euskadi’s long outdated (1979) statute of autonomy as having to be sanctioned by an “enabling consultation” of the population (as in the 2006 Catalan referendum over that country’s statute), the PNV keeps dodging implementation of this step.

It would represent an unambiguous affirmation of Basque sovereignty in support of a de facto confederal restructuring of the Spanish state and could well set Euskadi down the frightening road of ever-increasing conflict with the Spanish deep state, repeating the Catalan experience from 2012 to the present day.

All the signs point to a difficult life for the incoming PNV-PSE administration.

Firstly, because the PNV vote was strongest among the older generations, while the vote for EH Bildu prevailed among young people.

Secondly, because the EH Bildu vote was higher among Basque speakers, and the use of Basque is rising, especially among young people.

Thirdly, because the nationalist majority in the Basque parliament is now greater than it has ever been (54 seats out of 75), and this will make it harder than ever for the PNV to find excuses for not confronting the Spanish state over the Basque right to decide.

What now happpens in Euskadi will have a growing impact on Spain as a whole.

[Dick Nichols is Green Left’s European correspondent, based in Barcelona.]