Lyrikal Kombat

Red Eye Balaz

www.facebook.com/RedEyeBalaz

Kerser is one of the best-known acts in Australian Hip-Hop. The south-west Sydney emcee has built a huge following by pitching his hardened battle-rap skills against some of the biggest names in the game.

He now has more than 130,000 followers on Facebook and Twitter - not bad for a self-described "Centrelink bum" who had to release his music independently before overwhelming demand got him picked up by a national distributor. By comparison, the most popular Australian Hip-Hop group, Hilltop Hoods, have just over half a million followers.

Yet Kerser's lyrical content has dubious mainstream appeal. He blasts anyone with less-than-overt heterosexuality as "faggots". He releases songs about beating up "bitches", "sluts" and "wanna-be rape victims". His latest album ridicules female genitalia as "dirty little inflamed coffee beans".

But when Kerser got what some saw as his comeuppance, it came in unlikely circumstances. At a battle-rap in Melbourne, he faced an unknown Indigenous emcee who had seemingly come out of nowhere. Zone Doubt, who had stepped in for a rapper who had pulled out, was introduced with somewhat inaccurate hyperbole as "the world’s first Indigenous battle rapper". He proceeded to pull Kerser apart.

Video: GOT BEEF? - From The Ground Up - Kerser vs Zone Doubt. Got Beef? Entertainment.

Kerser's worst mistake may have been playing the race card. He said Zone Doubt looked like a cross between white Melbourne rapper Phrase and black American R’n’B singer Macy Gray - and compared his Indigenous opponent to Aboriginal pop star Jessica Mauboy. In the video of the event, you can see the indignation fire in Zone Doubt's eyes as Kerser spits out the lines:

When you rap, you make me hate hearing rhymes

Plus you look like Jessica Mauboy lost her razor and spent eight years on ice

When I rap, it's dope rhymes, these cunts know it's showtime

And you're the cunt that steals the socks off my clothesline

If I can't be bothered rapping I'm a pull out razor blades

Looks like they stole the face of Phrase and placed it onto Macy Gray

In an artfully articulate response, Zone Doubt turned the tables on Kerser and his crew by playing the race card right back at them:

It kinda makes me sick

Seeing these south-west white boys acting like they Grape Street Crips

In the end, Zone Doubt was unanimously judged the winner. The video has clocked up more than 300,000 views on YouTube.

'He, as a person, is garbage'

Three years on and 2300 kilometres away, Zone Doubt sits on a park bench at the other end of Australia and reflects back on that fateful day battling Kerser in Melbourne. "I'll be honest," he tells Green Left on a warm winter's day in his tropical hometown of Cairns. "He's garbage. He, as a person, is garbage."

Zone Doubt's accent pours like thick molasses squeezed from Queensland cane. As he speaks, rays from the mid-afternoon sun cut through the branches of a giant fig tree and glint gold off his wraparound shades. A week-long growth of beard curls up against their frames.

"When you're expressing in the battle rap, it puts you on the spot more than any other form of lyrical expression," he says. "You can stand there and say 'your mama' jokes all day or you can HURT that man, by saying certain things. Honestly, I don't think he had any content on me at all, and the moment he started talking about family, that's disrespect. That's not battle rapping to me. It was just race jokes. It was just inappropriate."

To be fair to Kerser, he has collaborated with west Sydney Aboriginal rapper Sesk and has even taken him on tour as a support act. Yet the conditioning of a racist society can be so strong that even Nelson Mandela has told of his panic when he once boarded a plane flown by a black pilot. Little surprise that even an ostensibly non-racist white Australian shows his true colours when placed on the spot in a battle rap.

"Yeah, that's it," says Zone Doubt. "That's what I mean. If you're gonna say that you obviously have a feeling about the whole race thing."

Zone Doubt's friend Isaac Raymond, sitting on the bench next to him, nods in agreement.

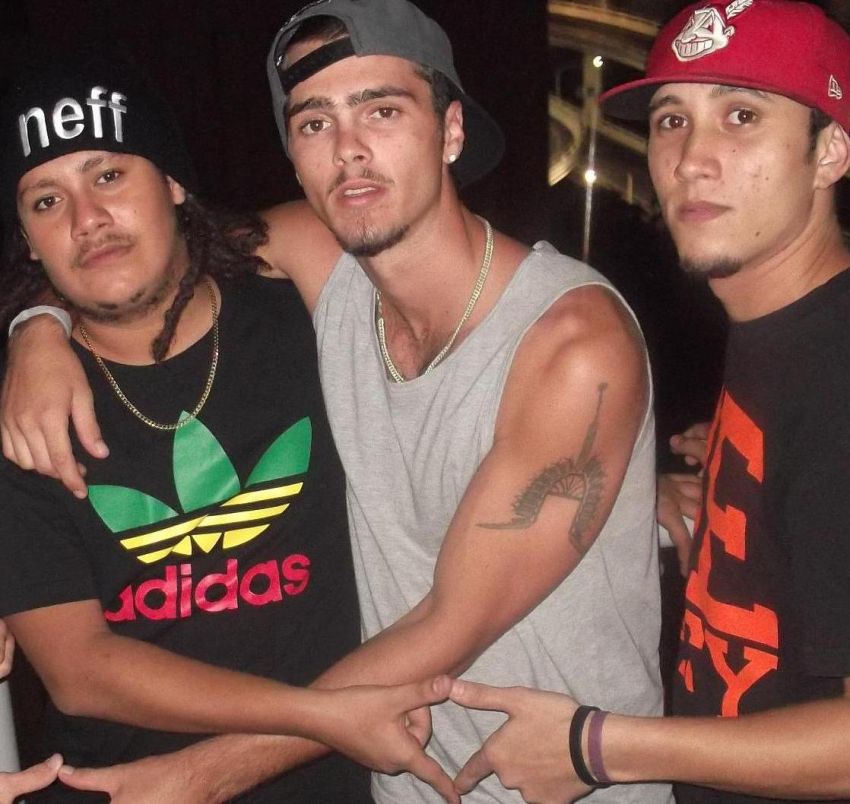

Red Eye Balaz, from left, ETP, TRUTHH, Sen Sei, Zone Doubt, B-mac and BSK.

"Yeah," says Raymond, otherwise known as Bala Sound Killa, or BSK for short. "What if he was in our hometown? Would he have still been saying the same thing if he was up here? Nine per cent of the population up here are blackfellas."

It's a notable figure. Aboriginal people make up only 3% of the national population and are usually marginalised, living at the fringes of mainstream Australian society. Yet in Cairns they are a strong, visible and palpable presence - even if they have moved towards mainstream society, rather than mainstream society moving towards Indigenous culture. In this city, Indigenous people are seemingly everywhere. "That's why we love Cairns," says Zone Doubt.

A good few of Cairns' young blackfellas are proud to call themselves members of Red Eye Balaz, a loose collective of hydro-huffing hip-hop heads to which Zone Doubt and BSK belong. Yet BSK says he became so disillusioned with the commercialisation of hip-hop that he ended up running a reggae radio show instead.

'I like the militant side'

"I like militant music," says BSK, who broadcasts his weekly reggae show on Cairns's Indigenous radio station, Bumma Bippera media 98.7FM.

"I grew up around reggae music, like Gregory Isaacs, Jimmy Cliff, Bob Marley. I like the militant side, 'Buffalo Soldier', those kind of songs. It makes you feel strong for who you are."

Like Marley, BSK grew up half black and half white, caught in limbo between the two worlds.

"You hang out with the white people and you're not white, and you hang out with the black people and you're not black, so you're like on both sides of the fence," he says.

Like Marley, he also lacked a father figure. "My father passed away when I was 10," he says.

BSK's brother, Elijah Raymond, says: "There is a lot of death in my family - close to one a year - so it's hard to move on when you haven't mourned the last person, when the next person goes."

Elijah, who records under the name Elijah The Profit, or ETP, raps in "So Far Gone": "How can we move on when all I see is casualties?" He also raps about their father's death on his song "One Day (Fade Away)".

"He passed away when I was 14," says ETP. "It plays in the back of my mind every day. My father was in my life up until my parents split when I was 11 and we hardly saw him after that. My mother looked after me and my little brother BSK and still does to this day, by herself. She used to get up at four in the morning to go clean the local YMCA, then come home to take us to school and then move on to her next job until 2.30pm to pick us up again. My mother taught me the definition of hustle and there isn't anything on this planet that will be worth what she has given us."

Their father was also a hustler of sorts. On "My City (Cairns)", ETP raps:

Woke Up In The Cairns Base 1988

Instantly the crime rate had to elevate

"I was born in 1988 in the Cairns base hospital and my father at the time was a ganja dealer," says ETP. "So when I say 'instantly the crime rate had to elevate', I mean my father had to get money from somewhere to provide and we didn't care as long as we had food on the table."

Zone Doubt, who has known the Raymond brothers since childhood - "we used to bath together", he says - also lost his father at a young age. His father died, like Bob Marley, at just 36 years old.

"And for reasons unknown, too," says Zone Doubt. "My father, he was from Thursday Island, that's where the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander comes from, but my mother's actually Italian and English. So I'm real mixed.

"My father passed away when I was 10 years old and my mother raised me and my two brothers. Dealing with that as a young kid, it was hard stuff to go through. I was lost. It teaches you some shit when you don't have a dad around. You've got to learn to be a man and you've got to learn every mistake by yourself. It's hard - it's not the same as every other kid, growing up with a family. But everything happens for a reason. It makes you who you are today."

Zone Doubt had to find his own identity. Like him, the Raymond brothers also had to seek out the Torres Strait culture of their late father, who was from Badu and Hammond Island.

'They talk about how good your dinghy is'

Says BSK: "I just went there recently, for the first time, last year. It was a big eye-opener. When you talk to the other side of my family, the full-blood family, they don't understand you because you grew up here, they grew up there, in the Straits, so they have different actions.

"The way we talk, walk and dress is different to the people in the Torres Strait. They don't talk about how good your car is, they talk about how good your dinghy is. Everything up there is different. Everyone loves it up there."

Yet for all of Cairns' multiculturalism, Torres Strait Islanders still have an image problem. "They're just labelled as 'the parkies', you know," says Zone Doubt. "I hate that shit."

BSK nods. "They don't understand in Cairns why these people are on the street," he says. "They come from places like Torres Strait when they need the medical treatment. The government flies them down but won't give them money to fly them back. So they come down here, they get their medicine and then they have nowhere to stay, they can't go home because they have no money. They're not on Centrelink or anything, they live off the land up there, so they get stranded here - and that's when they become the stereotyped parkies."

It's also why the men live such short lives, they say. "We need the men to start being more healthy," says BSK.

Zone Doubt says the answer lies in the power of a good example. "We need more role models. There's not enough role models, especially for Indigenous. We need to have an Aboriginal prime minister."

He laughs. Until that day comes, Red Eye Balaz hope to strengthen their culture through music and a better understanding of their history.

"I don't have as much history as I want," says BSK. "I don't know a lot of Torres Strait history, but I know a lot of black history around the whole world, Marcus Garvey, Haile Selassie I, Huey Newton. I get into history, you know, like black history. I try to educate from music, because people listen to music."

On the Red Eye Balaz track "Lyrikal Kombat", BSK raps:

113 years of slavery, we still strive,

Born to survive, now you must be feeling like the tide's rise

"It's our time," he says. "We've been under white people and that's when they took over Australia, in 1901. That's all history man, that's why I let you know what you need to know. You need to know your history of hip-hop, then your history of where you're from, everything. Because if you don't have history, you don't have knowledge. Then what are you going to talk about on your record? Nothing. Bullshit."

Sometimes, literally bullshit. The best line on the critically-acclaimed new album by bestselling Australian Hip-Hop act Bliss N Eso is: "Yo, my crew's on some bullshit. And I ain't talking about a poo that a bull did."

Zone Doubt laughs. "We're trying to speak knowledge," he says, "not bullshit."

Red Eye Balaz deliberately distance themselves from Australian Hip-Hop, describing themselves as "hip-hop from Australia, not Australian Hip-Hop".

"Hilltop Hoods, they're the classic," says Zone Doubt. "That's Australian Hip-Hop and if you compare our sounds, they don't even think we're from Australia, you know what I mean? We're reppin' the music, not the name."

ETP agrees. "I'm over the lack of content in Australian Hip-Hop," he says. "A lot of people nowadays spend more time at the gym than they do educating themselves." On his song "Stop Flexin", ETP raps that "your strongest muscle is your tongue". And he plans to make it stronger.

'We all come from the same planet'

"If I can make a difference, I will," he says. "It's time for educating, growth and for every man to be equal, regardless of their ethnicity. The way I look at it is, we all come from the same planet - and that's all there is to it."

Bob Marley, who famously tried to unite Jamaica's warring political factions by making their opposing leaders shake hands on stage, once said: "Me only have one ambition, y'know. I only have one thing I really like to see happen. I like to see mankind live together - black, white, Chinese, everyone - that's all."

It's a sentiment that seems to be at the heart of Red Eye Balaz and the core of Cairns, which now feels light years from the dark days of state premier Joh Bjelke-Petersen, even if present state premier Campbell Newman is little better.

"Queensland is a different state to the whole of Australia, because of the mixture," says Zone Doubt. "You know, you go down south and they're all in one lane, doing the rat race, like, you exist in your own little lane, but up here it's more communal, you feel the love. And that's where we're from. We were raised on the beaches, we walk the streets. That's how you gain love for your community."

As we talk, various passers-by drift past from the concert that is closing NAIDOC week just metres away in Fogarty Park. Many stop to say hello, shake hands, and slap the Red Eye Balaz boys on the back. It's a far cry from the rap battle-scarred streets of south-west Sydney, and Zone Doubt knows it.

"I'm known as a battle rapper, but I don't battle rap," he laughs. "I wasn't even meant to do it. I got asked two weeks before the event, they were missing a spot and I jumped in. I don't want people to know me as a battle rapper, I'm not a battle rapper. We don't want to advocate violence."

BSK nods and laughs. "We're militant rebels," he says. "Like Bob Marley, we bring freedom music, not violence music."

Download a free book and radio shows on Aboriginal hip-hop here.

Video: Zone Doubt response to GotBeef!!! ZoneDoubtGenZ.