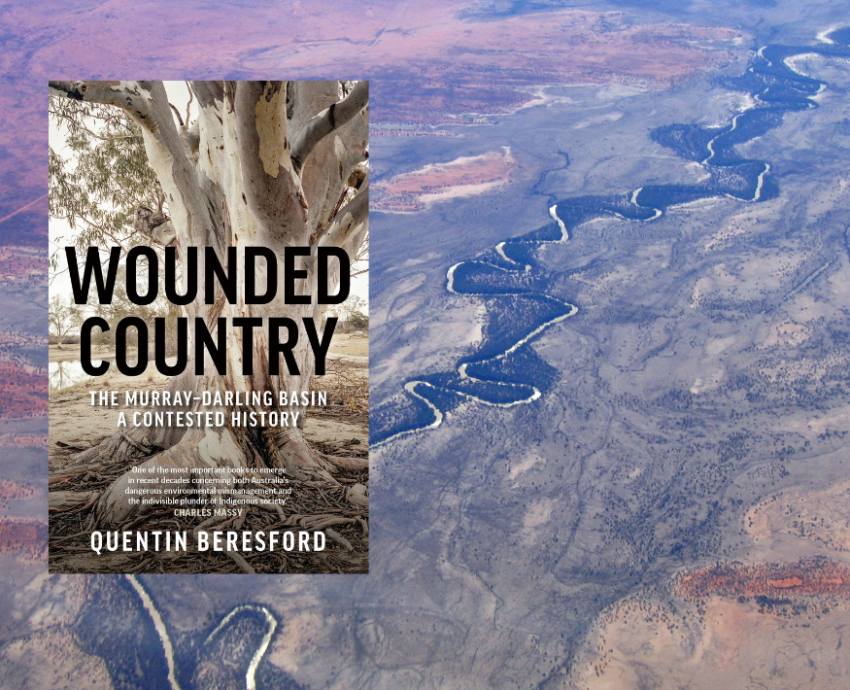

Wounded Country: The Murray-Darling Basin — a contested history

by Quentin Beresford

2021, New South Books, 432pp

Relying on contemporaneous media, journals and authoritative commentary, Wounded Country charts the deeply contested history of the nation’s food bowl and key river system.

Historian Quentin Beresford describes the ”settlement” of Australia as the world’s largest land-grab, driven by the British colonial frenzy to feed wool to the expanding textile mills of its industrial revolution and of Federated Australia chasing international trade, first in wheat and then irrigated rice, cotton and nut crops in marginal country.

Beresford recounts the dispassionate wayfaring of explorers Charles Sturt and Thomas Mitchell, who denied the rights of the original inhabitants and the natural capacities of the land, which they envisaged solely for pastoral development. He provides a significant historical record of the savagery of the dispossession of the Aboriginal people as the squatter class and their convict servants routinely slaughtered the original inhabitants with firearms and disease to secure their pastoral wealth:

“This was ‘settler capitalism’ at its most basic. Between them, the squatters and the banks had, for many years, the land ‘almost on their own terms’. This coalition of interests made pastoralism politically powerful, a power that was exercised ‘to reap their share of the plunder’, as one colonial newspaper wrote.

“The vast river system of the Murray Darling provided access to permanent water.”

Beresford sees the squatters rise to power as an instructive model for the Murray-Darling Basin, where vested interests have captured the political system to control the resources.

His account describes the colonial occupation/settlement as the establishment of a type of feudal relationship:

“The exploitation of both Aboriginal and white workers underpinned the wealth accrued by the largest of the squatters. Consequently, they became the first of the Basin’s powerful political lobby groups. Their model of wealth extraction based on monopolisation of the political power left an enduring legacy in the Murray-Darling Basin.”

Later in the 19th century and under "populate or perish" paranoia, selectors were given access to the less favourable portions of land. Beresford finds a cascade of mismanagement and abuses against the natural system as pastoralists and selectors, under the goal of making every hectare payable, cleared the trees and flattened native grasses for pasture and crops.

Beresford’s account of Australia’s war on nature echoes the recent works of Bill Gammage, Bruce Pascoe and Don Watson. Any native grass-eating animals, even birds as well as carnivorous dingoes and wedge tailed eagles, were seen as an enemy of the pastoral empire-building and the promise of a wool and wheat boom.

Forests were felled for railway sleepers or just ringbarked, burnt and cleared as a mark of ownership and development. With the trees gone, rainfall declined, overgrazing and overcropping saw soils collapse. Rabbit infestations ate out even introduced pastures and intensifying drought brought the pastoral industry to its knees.

Beresford includes in his tale of the Basin the people who have suffered the impacts of dispossession, loss and environmental disaster, bringing forward the poems, paintings and prose that speak even more directly than the staggering figures and dire warnings, too easily buried from public consciousness. Wounded Country reminds us of those who have toiled and suffered the losses of land, culture, communities, the rivers and the flora and fauna that depend on them.

Beresford provides evidence that the failure of the bid to render Australia’s inland to an agrarian utopia of independent yeoman farmers wrought catastrophe for the environment. Unearthing a too-easily-buried record of increasingly frequent and enduring drought; sand drifts and dust storms, Beresford describes an exodus from the Bush at least equal to the rural collapse of the American mid-West in the 1930s.

But the new nation failed to respond to the crisis with the American resolve. There was to be no agreement between the States for a US-style ‘conservation miracle’ of wind breaks, tree planting and compensation packages to farmers to reduce their acreage under grain. A piecemeal response of ‘small government’ soil conservation services and later water managers have tried to encourage reform for the public good and curtail the ambitions of powerful landowners who have swept up the land holdings and water rights with them.

Unlike many other analyses of the Basin, Beresford marries both the history of land use and water use and their social impacts. As irrigation became the new elixir to revive the ‘wastelands’ and turn them to productivity, it also concentrated wealth in the hands of fewer and larger scale agriculturalists. Beresford provides a history of the irrigation schemes, water capture and unsustainable agricultural practices which captured the rivers, contaminated and drained wetlands, resulting in disastrous salinity and raised water tables.

Beresford gives a gratifyingly clear, short history of water management and ownership between the states under the Commonwealth’s most contested legislative power, the 2007 Water Act. He charts the political failures of the National Water Initiative’s endeavour and the controversy surrounding the Federal water license buy backs — the bid to address historic over-allocation of water licences and set realistic State Diversion Limits (SDL) to balance the water demands of the Murray Darling Basin’s four states.

He accounts well the overturning of the environmental priority of the draft Murray Darling Basin Plan, which met with a tumult of resistance from farmers in the Southern Basin. The Northern Basin water barons capitalised on inflated government buybacks of their more tenuous and surplus holdings.

State Water Ministers have seen to it that implementation of the Basin Plan has delivered for entrenched economic interests and the status quo that has weathered on, over a century of boom and bust. NSW has exempted one of the key diversionary practices, flood plain harvesting. The erection of massive private dams has been funded by money set aside for environmental water. It is now seeking to hand out licenses (for free) to legalise a practise now taking as much as 40% of river flows in the northern basin, with no regard to the State’s SDL. The National Party continually threatens to withdraw from a multi-state agreement on water management.

Beresford makes it clear that the Basin has fallen victim to short-term political and economic interests. He navigates the political interference, rule breaking and corruption with a snapshot of the grosser abuses of power and control of water. In this, the National Party is highlighted as historically opposed to reform and clearly a protector of corporate interests, rather than the environment or even agriculture.

Beresford delivers an overview of the nexus between powerful corporate irrigators, water capitalists, lobbyists and their deeply embedded political representatives. But he gives the least attention to largest force reshaping of the Basin: the free market for water; the ultimate conquest of environmental and social values by economic rationalism.

As expert water analyst Maryanne Slattery points out, Australia has implemented the largest privatisation of water in the world. Under the free market — despite the best intentions of environmental water holders, community water sharing plans and the traditional owners who have never ceded their country, or even national water authority — Australia’s shrinking water resource has been dedicated to increasingly flow to those with the deepest pockets and the biggest pumps. Water is a finite resource, a human right and source of all life, yet in Australia water is capital.

Amidst the unfathomable complexity of water and land use in Australia, Wounded Country is an accessible account of how we got to the impending death of our rivers. It gives a provocative record of voices from the frontline of the land and water grab of the past two centuries.

Beresford helps identify the brutality of extractive agriculture, the disaster of utopian thinking and unending profit-taking which has denied the natural constraints, indigenous knowledge and science which could provide fairer more sustainable land and water use. It offers a valuable reflection on how we might learn the lessons of history to address the man-made inequities and environmental degradation that threaten our nation’s food bowl and our future on this continent.