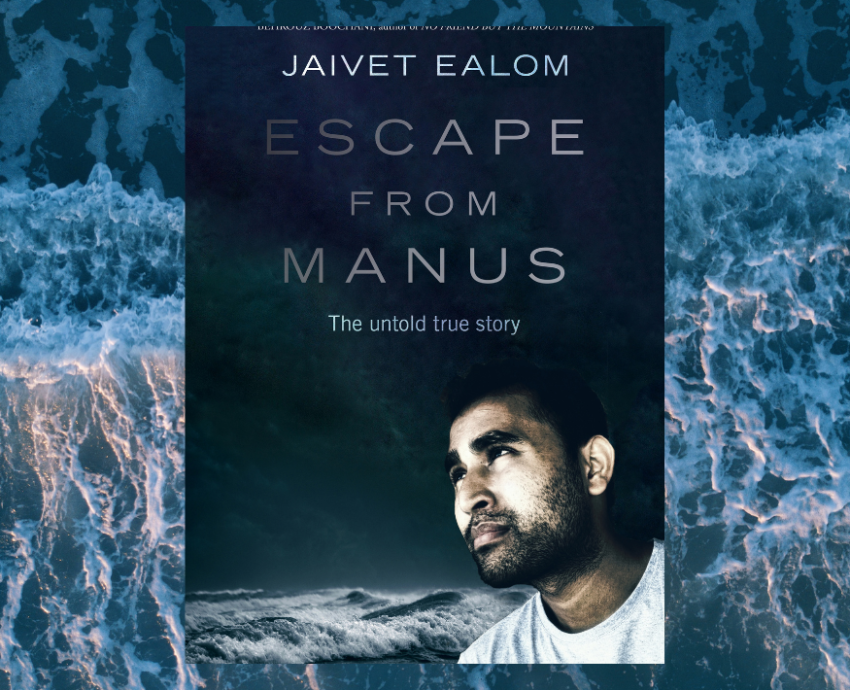

Escape from Manus

By Jaivet Ealom

Penguin Random House Australia

First Published by Viking in 2021

Escape from Manus is a compulsive read. It has the hallmarks of a great escape, and chronicles — in detail and with incisive political critique — the brutal prison system that is the lot of asylum seekers and refugees seeking safety on Australian shores.

Jaivet Ealom describes his early years growing up in a “roofless prison” that was Rakhine province in Myanmar. He was born a decade after Burma’s military junta stripped the Rohingya of their legal existence and pursued a campaign of oppression and harassment, corralling his family into a proscribed area ringed with military checkpoints.

At 21, Ealom fled persecution in Myanmar, finding himself on a small boat with 100 other men, women and children. Their destination was Darwin, but they were plucked out of the ocean by customs officials and taken to Christmas Island, strip-searched, given a numbered tag and imprisoned in the island's detention centre.

“The facility was an estate of low, grey, steel-roofed buildings, covering an area bigger than twenty soccer fields. It was not at first glance a welcoming place.”

Serco is employed to manage the facility. Ealom wryly notes their “sunny” tagline: “Bringing Service to Life”. Here, Ealom becomes EML 019 – his designated number. And the message is hammered home — at every available opportunity — that Australian law has changed (just 5 days prior to their boat’s arrival) and that no one entering Australian territory by boat and without a visa will be allowed to claim asylum.

They are informed they will be transported offshore to either Manus Island or Nauru and held in indefinite detention while their claims are processed. Over time, they hear more detail — that a new Prime Minister called Kevin Rudd has taken over from Julia Gillard and introduced these new rules.

In a tragic irony, the prisoners follow the events of the subsequent federal election and are elated when the election is won by the opposing political party in the form of the Coalition’s Tony Abbott. They hope this new political leadership will overturn the harsh policy.

But their expectations are soon dashed. Two weeks later Abbott launches Operation Sovereign Borders, which has as its message, “NO WAY: YOU WILL NOT MAKE AUSTRALIA HOME”. The hypocrisy of this coming from a country that has been built on a hostile take-over by sea is not lost on Ealom.

The move to Manus reminds Ealom of home. “For those of us who had grown up under a military regime, this was a nightmare,” he writes. “The dark green of those Manus tents struck my eye as the same shade as the uniforms of the Burmese soldiers. It was the colour of despotism the world over.”

Ealom details the deliberately bleak and demoralising conditions on Manus, the impossible heat from which there is no escape, the rancid slop often alive with maggots that is served up as an excuse for food (when there is enough to go around), the deliberate actions of the guards designed to break down solidarity among fellow prisoners, the totally inadequate and unhygienic nature of toilet and shower facilities.

Ealom labels the government mantra that Operation Sovereign Borders is all about saving lives at sea as “diabolical spin”. “If people weren’t drowning in the Indian Ocean, there were a thousand ways of dying a slow death in the ghettos of holding-cell countries like Indonesia and Malaysia, or faster ones in the strife-torn countries we once called home.”

Ealom’s book charts the Abbott government’s militarisation of its immigration arm. Starting out as the Department of Immigration and Citizenship, the Coalition first renamed it the Department of Immigration and Border Protection and finally, Australian Border Force.

Then-immigration minister Scott Morrison’s message that those imprisoned on Manus would spend years in detention was, he says, like a “non-stop finger in the eye”.

Ealom reports the advent of peaceful daily protests calling for “Freedom”. On February 16, 2014, following yet another pronouncement that processing could take anything from 6 months to 10 years, more significant demonstrations flare. There are scuffles and some detainees are injured. It is rumoured that some prisoners have escaped and been harmed by “Papu” villagers.

That night, the prison comes under attack. The generator shuts down and the compound is shrouded in darkness. The events of that fateful night, which resulted in the death of 23-year-old Iranian Kurd, Reza Barati, are described in terrifying detail by Ealom, who is himself seriously injured by a G4S guard.

He later wonders at the ferocity of the attack but learns, years later, that the flames had been deliberately fanned. Locals had been told the refugees and asylum seekers were hardened criminals, sent to detention on Manus because they were too dangerous to be housed in Australia. The first to fire their guns were members of the Papua New Guinea police force.

Ealom is advised in 2017 that he will either be returned to Myanmar or sent to prison in PNG. He makes the decision to escape. What follows is a gripping and extraordinary story of his 6-month-long journey from Manus to Port Moresby, the Solomon Islands and finally Toronto, Canada. In planning his escape, he draws inspiration from US television series, Prison Break.

Today, Ealom lives in Canada, where he has become a prominent spokesperson for the Rohingya people. He is studying at Toronto University and works for a company that provides software to not-for-profit organisations.

Escape from Manus is one of those books you just have to read. It’s too important not to. It is at once a powerful human story and a devastating polemic against Australian government policy that demonises and shuns those fleeing their homelands for safety.

“There had been a time when I had considered Australia, as much as I thought about it at all, as a civilised country, with egalitarian principles that gave me hope for the future,” Ealom writes. “Now I knew the Antipodean utopia was a myth. From where I stood, this first-world-democracy served up the same shit as back home, just in different colours.”

[Janet Parker is an activist with the Refugee Rights Action Network WA.]