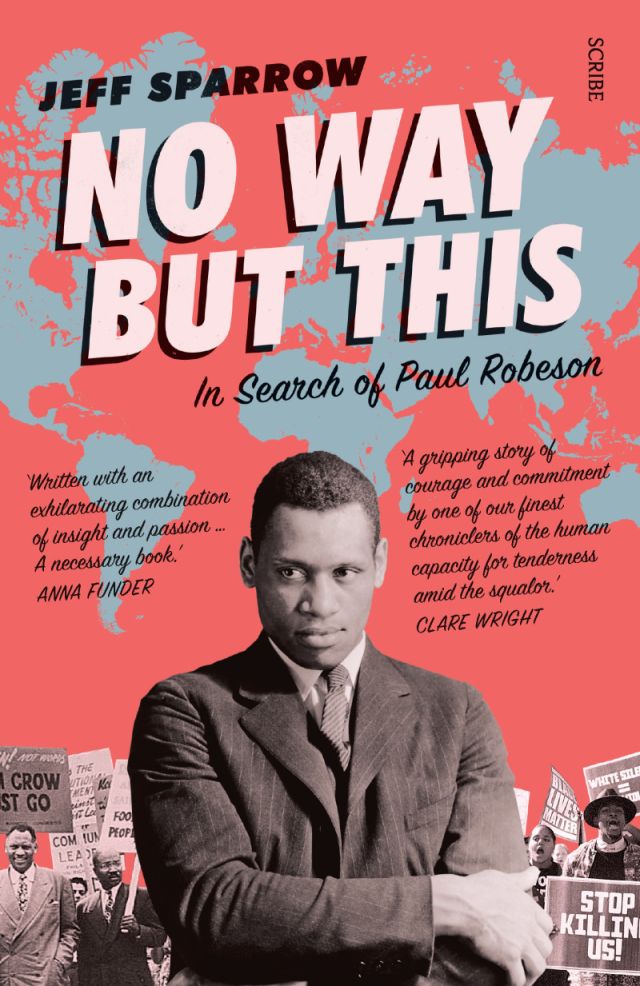

No Way But This: In Search of Paul Robeson

By Jeff Sparrow

Scribe Publications, 2017

Paperback, 292 pp

Melbourne writer Jeff Sparrow’s new book, No Way But This is a thoughtful, sensitive and respectful examination of the life and work of Paul Robeson, the great African-American baritone, Shakespearian actor, and left-wing political activist.

The book deals with complex political and personal matters in beautifully flowing prose, and links the past with the present and the challenges of the future. Born in 1898, Robeson was a towering figure in his day and this book will introduce him to a generation that has scarcely heard of him.

And there are so many reasons why he should not be forgotten. Sparrow’s penetrating study is no hagiography and he does not flinch from confronting the Stalinist blight that wrecked the international socialist movement and caused Robeson so much pain.

Sparrow tells us that in his search for Robeson, he embarked on a ghost-hunt that took him to many of the places where Robeson sang, loved, acted and fought for the dignity of his downtrodden people and the workers of the world.

Ghosts crowd every nook and cranny of the book: those of slaves and slave-owners in the Deep South; Black writers and activists in Harlem; white miners in the South Wales valleys who taught the Black Robeson the meaning of solidarity; tough building workers who cried when Robeson sang to them on the site of Sydney Opera House; those who fought and died in a losing battle against fascism in Spain; and the victims of Stalin’s Gulag.

In one of the most moving passages of the book, Sparrow and a Catalan comrade visit the valley of the Ebro, the scene of the Spanish Republic’s last desperate attempt to turn back Franco’s fascist hordes in 1938. Respectfully, they gather the bones of a long-dead Republican soldier and mark the spot with a cairn of stones.

Perhaps the bones were those of Sparrow’s own uncle, who died aged just 18 fighting for the Republic? Vindictive to the end, the fascists refused to allow Republican families to bury their dead, leaving the bodies where they lay.

More than the biography of one remarkable man, the book is a testament to Robeson’s conviction that despite it all, there was no way but to struggle for a better world. This is as true for us as it was for Robeson.

As a child and a young man, Robeson strove to follow the prescription of his ex-slave father: that by educating and bettering himself — surpassing the whites around him — he would help emancipate Black Americans.

A brilliant student, Robeson also outshone his white students on the sports field and in every other campus endeavour. Once graduated, but for the colour of his skin, he could have been an eminent lawyer. Instead, he put on his hat and left the New York legal practice where he had recently been employed when a white stenographer informed him that “I don’t take dictation from niggers”.

From that moment, perhaps, the iron entered Robeson’s soul. Although he never formally joined the Communist Party, he supported it as the only organisation he knew that treated Black people as equals of whites. He never publicly recanted his support for the party, despite the considerable hardships that stance brought with it in the dark days of McCarthyism and the Cold War.

Hauled up before the House Un-American Activities Committee (HUAC), Robeson stared down his racist interrogators and “began to ask his own questions”.

The HUAC chairperson, Francis E Walter, was “a thin-lipped Democrat from Pennsylvania [and] … a director with the Pioneer Fund, an organisation that promoted eugenics”. He was an architect of racial restrictions on immigration into the US.

When Walter demanded to know why Robeson did not go and live in Russia, Robeson replied: “Because my father was a slave … and my people died to build this country, and I am going to stay here, and have a part of it just like you. And no fascist-minded people will drive me from it. Is that clear?”

Yet the question of Russia weighed heavily on Robeson’s mind. In Moscow at the time of Khrushchev’s famous “secret speech” that admitted the crimes of Stalinism, Robeson was struck down by a nervous breakdown and fell into terrible depression that never completely lifted.

And here we come to the crux of a dilemma that assailed not just Robeson, but the entire left.

Visiting memorials to Stalin’s Gulag, Sparrow ruminates on the legacy of Stalinism: “The Soviet Union, a society in which millions of people had lived lives crossed with barbed wire, deserved to fall … But that didn’t invalidate the old yearning for a different kind of world.

“If you believed in nothing, you’d fall for anything. Without a vision of a better future, without the sort of hope that Paul had given voice, the dictators would always return ...

“We urgently need to exorcise the ghosts of the recent past. We need an exhumation of what has been repressed; we need to remember all that we have tried to forget.”

His concluding sentence nevertheless offers words of hope: “Paul Robeson was dead, but his story wasn’t over.”

Today, with the left weakened at precisely the time when it is most needed — when dictators again stalk the world, Black Americans still face oppression, and capitalism is destroying the planet — there is still “no way but this”, the way of struggle.