Campaign group Action for Public Housing (APH) is ramping up its activity ahead of the New South Wales election on March 25. With the housing crisis getting worse, the need for a massive expansion of public housing could hardly be more urgent.

House prices have skyrocketed over the last few years, despite being already way too high even before the COVID-19 pandemic. Rents in Sydney have risen 19% in the past 12 months and homelessness is rising, with women over 50 the fastest growing cohort.

A common refrain from developers is that prices are rising because of lack of supply. They blame regulations and “nimby” (not in my back yard) campaigners — despite consistent evidence against the claim.

An interesting graphic on the ABC news recently confirmed this. Housing construction over the last eight years has averaged about 200,000 homes per year. At 2.5 people per household, this has raised housing capacity at 500,000 people per year. However population growth is averaging 300,000 a year and rarely exceeds 400,000 in any one year.

During this time, house prices have increased far in excess of incomes.

It is clear that housing in Australia is not following any naïve economic theories of supply and demand. Why is that?

The problem is that rather than being a human right, providing an essential human need, housing is seen as an investment. Financial arrangements, such as negative gearing and capital gains tax exemptions, reinforce this as do lax conditions allowing landlords to raise rents and evict tenants at whim.

MPs from both major parties have absorbed this investor–style thinking, even when it comes to public housing. The NSW Coalition’s Communities Plus model “optimises” its public housing stock by selling it off.

In NSW, more than $3 billion worth of social housing has been sold off over the last 12 years. The current fashion for government “shared-equity” schemes is funded and predicated upon making a profit when housing is sold.

When interest rates are lowered, the price of houses just increases to the higher level of loans that investors and homebuyers are allowed to borrow. First home buyer schemes have a similar effect.

Under such conditions, building more houses in the private market is a bit like printing money. Who benefits depends on who the money, or the house, goes to.

Approving a development or rezoning land for residential or increased density is essentially a gift of public assets to a developer or land owner. It’s a bit like printing money and only giving it to rich people: it makes everybody else relatively poorer.

When presented with this problem in other areas of essential human need, the answer has been to take matters out of the market and provide the goods directly. Hence, we have public health, public education and public transport.

It should be no different for housing.

It’s clear that we need to massively increase the public housing stock, which has fallen as a proportion of all housing from 6% in 1989 to 3% now.

Historically, public housing was built in times of serious need, such as after WWII, and in sectors identified as more worthy, such as defence worker housing.

As the stock of public housing has decreased, eligibility criteria have become increasingly strict, to the point where public housing is stigmatised as “welfare housing”. That needs to change.

Vienna, Austria, has 60% public housing; Sweden has 20% and, in the 1970s, nearly a third of British households were living in public housing. Housing investor tax concessions, which cost the budget $20 billion a year and overwhelmingly benefit high income earners, should be scrapped and used to get us up to these levels.

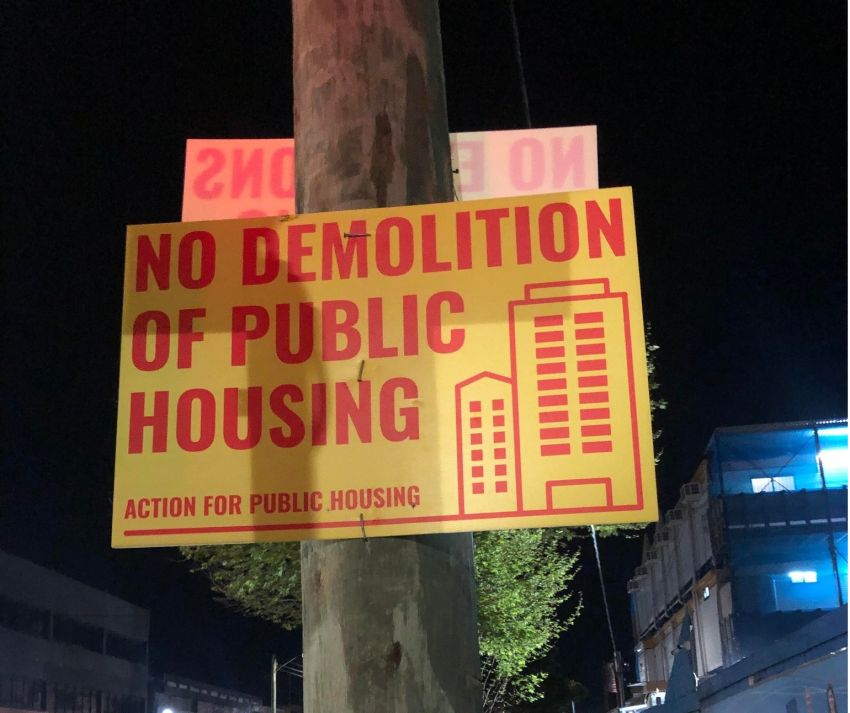

APH has been running campaigns calling for a stop to public housing demolitions in Waterloo, Glebe and Eveleigh, while pushing for new public housing to be built in suitable locations, like the now vacant 600 Elizabeth Street, Redfern.

Along with Hands off Glebe, APH has been holding monthly pickets and organising meetings, running online petitions and sharing information, via a mailing list. It has also held free BBQs to raise awareness at public housing estates under threat, such as at Wentworth Park Road in Glebe.

A rally for housing justice on February 11 at 12pm at Sydney Town Hall is being endorsed by a growing list of resident, student and tenant groups, as well as Socialist Alliance and the Greens NSW. It will feature a broad spectrum of speakers.

The rally is demanding that homelessness be eliminated; that quality public housing and wrap around services for people who don’t have secure housing be guaranteed; that public housing is defended and extended; and that there are no demolitions, no privatisations and no evictions.

The rally is also calling for the repair and refit of existing public housing, for 100,000 new public homes to be built over the next four years; to keep public housing under public management and to reverse the outsourcing to community housing companies.

Finally, it will raise the demand to freeze all rents for two years, end no-fault evictions and introduce a vacancy tax to force vacant homes and permanent short-term rentals into the rental system.

The demands are bold, but necessary. With sustained people power they can be achieved.

[Andrew Chuter is a member of Action for Public Housing. He is running for Socialist Alliance on the Legislative Council ticket.]