Kenya’s War of Independence: Mau Mau & its Legacy of Resistance to Colonialism and Imperialism, 1948-1990

By Shiraz Durrani

African Books Collective, 2018

The public relations department of the colonial government in Kenya never referred to the Mau Mau struggles as a “war of independence” during the post-World War II years. Rather, the struggles were relegated to an “emergency” where the colonial government had to deal with “a frenzy of violence”.

Shiraz Durrani’s book sets out to document “the historical resistance of the people of Kenya against colonialism and imperialism during a long war of independence and liberation with many different stages”.

After Kenya gained independence from the colonial power of Britain in 1963, another war was waged that Durrani describes as “the war of economic independence”. In the latter, the resistance was on political and economic fronts “against the comprador regime installed by the departing colonial government as neo-colonialism tightened its grip on Kenya”.

The British government, together with the settlers who were offered very favourable terms to put down roots in Kenya, were replaced by corporations from the United States and their allied advisors of the International Monetary Fund (IMF) and World Bank.

Brutal exploitation

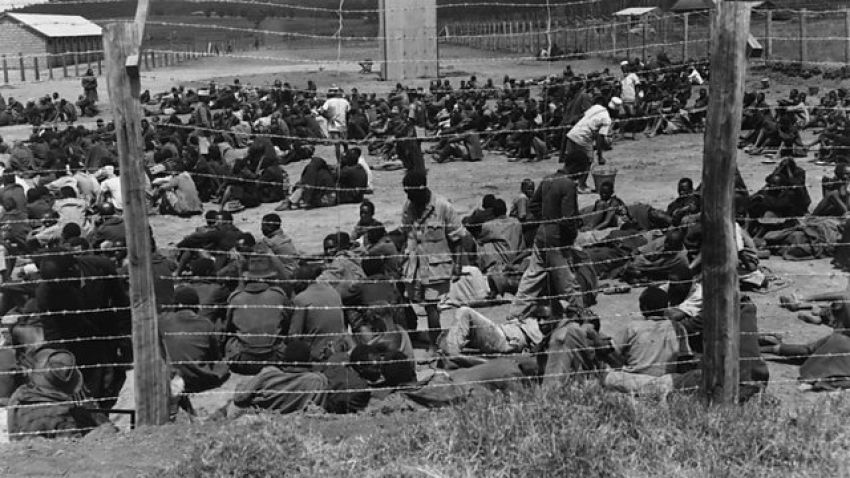

Durrani’s book sets out in four parts to provide an insightful reality on the brutality and exploitation by the colonial regime. The British used horrific torture methods on activists from the Mau Mau movement throughout the eight years of rebellion. The torture and brutality were usually deployed by the Africans who were either in the police force or in the military (King’s African Rifles).

Kenyan society under the colonial project was “a vastly unequal society”. Those who benefited from the disparities in the country were far away from the inhuman practices that were underway to make money for them. For example, peasants were controlled by kipande. This required all African men to carry a registration card (they were finger printed before the card was issued) under the Registration Ordinance of 1920. The sole purpose of the card was to control and restrict movement of adult African workers.

African workers were tightly controlled in the colonial regime, but the post-independence redistribution of land to the Kenyan workers was contentious. The 2015 Truth, Justice and Reconciliation Commission reported that: “The colonial system created ethno-specific boundaries, which gave the impression that land rights within particular boundaries could only be enjoyed by certain communities, in certain areas.

“These ethnic ties continue to affect Kenya to date”.

In reality, the African workers lost not only to the colonial regime but also to the post-independence government. The land settlement profited only the Kenyan elite. These elites did not need money to buy farms as they could easily get loans from the governmental bodies that were set up for the benefit of the farmers.

In the pre-independence period, Durrani attributes the Mau Mau’s success to its communication strategy. The cadres recruited by the resistance movement were able to form links with the working class, who provided information as they worked in the domestic service sector as well as the agricultural sectors. Workers in government departments provided information from official files, as well as everyday conversations.

The Mau Mau played a major role in the struggle for independence, but there were other actors in the resistance.

The role of South Asians in the struggle has been overlooked by scholars, until recently. South Asian workers were imported from the Indian sub-continent by the colonial administration.

They worked on the railways as they had the appropriate skills. But along with their skills for building the railways, they also brought their ideology and experiences of the struggles of the Indian working class against colonisation by the British and the Portuguese in India.

Durrani says that the contribution of South Asian workers and their resistance against colonialism in Kenya was significant.They had experience of resistance that enabled them to identify the enemies, which helped to focus the struggle for independence from colonialism, imperialism and capitalism.

Additionally, some of the critical ingredients in the resistance movement were provided by trade unions. The workers, through their experience of organisation and working-class ideology, provided the “behind-the-scene impact of the organised labour movement as an important contributory factor in the War of Independence”. Strike action by the workers hit at the heart of the “colonial, capitalist economy”.

Working class and women

Trade unions played a key role by creating a receptive working class that had very little to lose as the colonial administration had taken away their land, properties and livestock. When the livelihoods of people were threatened, the resistance with its collective action became a strong force against colonialism.

Women in the Mau Mau movement played a key role, particularly in the transportation of arms and food to the various camps throughout the country. They were also involved in spying and accessing guns and bullets. In the six years between 1954 and 1960, about 8000 women were detained under the Emergency Powers.

The combination of trade unions and the radical, nationalist movement did impact upon the colonial administration. Concerning the unions, Durrani writes they “provided the spark that changed the direction of the War of Independence. This led to the emergence of the armed resistance movement, Mau Mau, as the new approach to defeat colonialism and imperialism.

“The trade union movement provided ideological clarity and the national organisational experience; the militant national political organisations provided political structures and mass support developed over a long period.

“The former brought the working class to the struggle, the latter brought peasants, creating a national movement of all the exploited and oppressed people.

“Together they formed an iron fist that colonialism fought hard to defeat”.

The response to the resistance movement by the colonial administration was brute force, rather than seeking political solutions. The acts of brutality are only now beginning to be revealed in the remaining documents on the colonial rule. Some of these documents were destroyed or hidden when the colonial government left Kenya.

The practice of repressing the people’s demand for independence with military force was also common in other British colonies, such as Malaysia. The actions of the resistance resulted in the colonial government referring to them as terrorists, thereby masking the colonial government’s military ambitions.

Durrani states, at various points in the book, the importance of Kenya’s War of Independence as a movement that worked towards the liberation of all the people and not just a few. When the colonial government was in power, it manoeuvred towards creating hostilities and divisions between tribal, ethnic and religious groups.

This led to tensions among communities that were instigated “to create the impression that the interest of one ethnic group could only be enforced at the expense of another”.

The book ends with a discussion on the legacy of colonialism and neo-colonialism, with the War of Independence continuing in pursuit of economic freedom.

Durrani makes the case that Kenya is not really free, as the forces of international capitalism continue to have a stranglehold on the country. The political class deploy methods similar to those used by the colonial regime and remain in power.

[Reprinted from Red Pepper.]