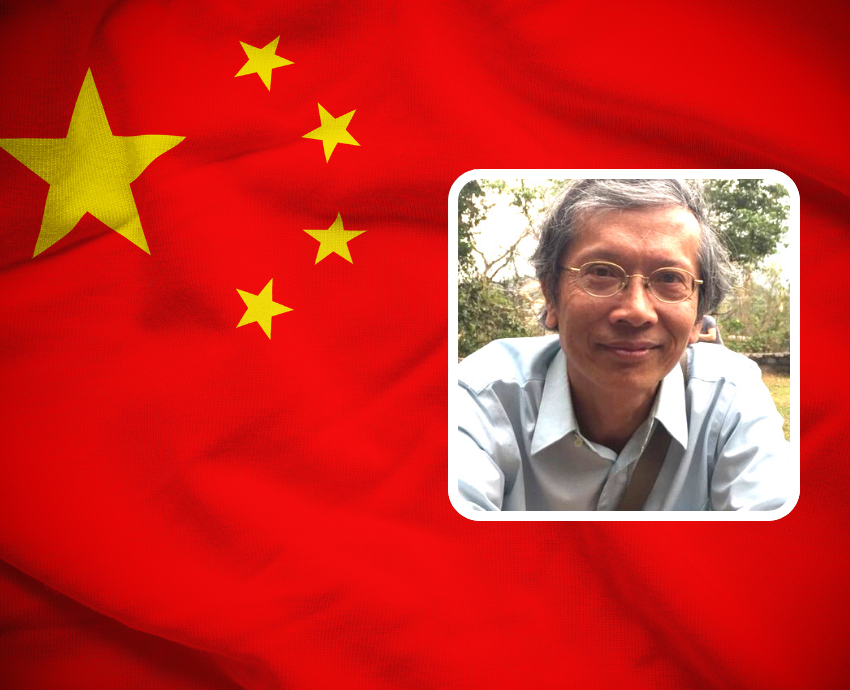

Hong Kong labour rights and political activist Au Loong-Yu talks to Green Left’s Federico Fuentes about China’s position in the world today and its implications for peace and solidarity activism.

How should we understand China’s status today?

For the past three decades China has not been a regular Third World country. From a largely peasant-populated country 40 years ago, today it is 60% urbanised and fully industrialised, manufacturing both low and high end products.

As a result, China has crossed the threshold to become an upper-middle income country according to the World Bank. Yet 600 million Chinese have a monthly income of only US$140.

China simultaneously contains many elements, making it very unique. Simply looking at GDP [gross domestic product] per capita or monthly income might lead you to believe that China is part of the Global South. But no single economic indicator can provide us with a definitive answer.

China still has elements of being a Third World country, but they remain just elements and their significance has diminished over time. To draw any useful conclusion on China, we have to take into consideration all its elements.

If China is not a regular developing country, does that make it imperialist?

China’s status is complicated. There is no clear cut “yes or no” answer; rather the answer is “yes and no”.

If we take [Vladimir] Lenin as our starting point, he refers to the degree of monopoly, the merger of industrial and bank capital, the formation of financial capital and capital export as defining features of imperialism. If we apply these to China, they are all present in a very significant manner.

But whereas in other parts of the world imperialist logic is driven by private capital with support from the state, in China the state and state capital are the major players.

China’s state is a predatory state entirely controlled by an exploiting class whose core is Chinese Communist Party (CCP) bureaucrats. I refer to this exploiting class as a bourgeoisified state bureaucracy.

In China we have a kind of state capitalism, but one deserving its own name. In my view bureaucratic capitalism is the most appropriate term for China.

It captures the most important feature of China’s capitalism: the central role of the bureaucracy, not only in transforming the state (from one hostile to capitalist logic — though never genuinely committed to socialism — to one thoroughly capitalist), but also in enriching itself by fusing the power of coercion and the power of money.

Does China also exhibit expansionist features?

As a strong bureaucratic capitalist state, it necessarily carries a strong expansionist imperative that is not just economic but political.

China’s extensive capital export, which often takes the form of long-term investments, means Beijing necessarily requires global political leverages to protect its economic interest. This objectively encourages an imperialist logic to dominate lesser countries and compete with leading imperialist countries.

But there is also a political expansionist logic. China’s century-long “national humiliation” under colonialism, between 1840‒1949, led CCP ruling elites to vow to strengthen the country at all cost.

[President] Xi [Jinping]’s dream for China should be interpreted in light of Mao Zedong’s dream of chaoyingganmei (超英趕美, surpassing Britain and catching up with the United States). While the slogan should not be interpreted literally, China’s ultra-nationalist rulers will not accept China remaining a second-rate power for another century.

This ambition, born from China’s contemporary history and the party’s great Han Chinese nationalism, has led Beijing to seek global political influence. It will also, sooner or later, lead them to seek global military power — if China can consolidate its status in the coming period.

Given all this, could you summarise your view on China’s status today?

I think we can say that China is an emerging imperialist country — a very strong regional power with a global reach. It possesses the intention and potential to dominate lesser countries but has not yet consolidated its position as an imperialist power.

In my opinion, the term emerging imperialism allows us to avoid certain errors. Some argue since China and the US are not on a par, therefore China cannot be imperialist. This argument fails to capture the constantly changing situation within China and globally.

We must be able to grasp both the universal and the particularities when it comes to China. Its potential to develop into an imperialist power is immense. It is also the first emerging imperialist country to have previously been a semi-colonial country. On top of this, China has to confront the issue of its backwardness.

These factors may have in part contributed to its rise, but certain aspects also continue to cripple its capacity to develop efficiently enough and, more importantly, in a more balanced way.

If we factor in the party’s failure to modernise its political culture of personal loyalty and cult leaders, we can see why China’s ability to consolidate its position at the table of imperialist powers faces difficulties.

What can you tell us about China’s actions in the South China Sea?

China’s nine-dash line claim over the South China Sea was a fundamental turning point, because it represented the start of China’s overseas expansion, politically and militarily.

China has never effectively ruled the whole area of the nine-dash line claim (excepting some islands, such as the Paracel Island). Its claim over most of the South China Sea is not only not justified, either under so-called international law or from a leftist point of view — it is a pronouncement of its hegemonic ambitions in Asia.

Are China’s actions not largely defensive, aiming to create a buffer against US militarisation?

I think that was true of China’s actions prior to its nine-dash line claim.

Even if we accept that China continues to act defensively and is simply responding to US aggression, you do not do this by invading huge territories that never belonged to China and which surrounding countries have claims over — including some who were victims of Imperial China’s aggression for hundreds of years.

This is an invasion of the maritime economic zones of several countries in Southeast Asia. It can no longer be deemed to be defensive.

Today, Beijing has both the intention and capacity to kick start a global contest with the US. We must continue to oppose US imperialism and militarisation in the region, but this should not mean supporting or remaining silent about China’s emerging imperialism.

How does Taiwan fit into US-China tensions?

The fundamental issue here is that China’s claim over Taiwan has never factored in the wishes of the Taiwanese people. This is the most important point. There is also the secondary issue of US-China tensions. But these tensions have no direct bearing on the fundamental issue.

Taiwanese people have a historic right to self-determination. The reason is simple: due to their distinct history, Taiwanese people are very different from those of mainland China.

Ethnically speaking, most Taiwanese are Chinese. But there are ethnic minorities, known as Austronesian peoples, who have inhabited Taiwan for thousands of years and their rights must be respected.

As for those who are ethnically Chinese, about 15% only moved to Taiwan in 1949 after the Chinese revolution.

The majority have descendants who have been living in Taiwan for up to 400 years. Most have no connection to mainland China — any such connections were broken hundreds of years ago.

Taiwan has been a separate nation for many years. It has a historic right to self-determination.

It is true that all this is now entangled with US-China tensions. In this sense it is similar to the Ukrainian situation. In that case too, there are those who support Russia or hold a neutral position. In my opinion, they are wrong.

There is no doubt that the US is a global empire that pursues its agenda everywhere. I understand that some Western leftists do not want to be seen as aligning with their own imperialist governments.

But our support for smaller nations’ right to self-determination — as long as we conduct it independently — has nothing to do with the US, or China for that matter. We support these struggles based on our principle of opposing national oppression.

What solidarity campaigns should the left focus on when it comes to Taiwan or the South China Sea?

Any solidarity campaigning on these two areas — to which I would add Hong Kong — should consist of at least three points: respecting the Taiwanese and Hong Kong peoples’ right to self-determination; accepting that China’s nine-dash line claim in the South China Sea has no basis; and acknowledging that agency for opposing China’s stance lies with the peoples of these three areas and surrounding countries.

[A longer version of this interview first appeared on links.org.au.]