The university sector was readying its begging bowls in the lead-up to the federal election. Poor investment decisions, notably in the Chinese market and COVID-19 had threatened to wipe the balance sheets of a number of them.

Despite some initial shocks, the storm has been, apart from a few institutions, weathered.

The University of Sydney (USyd) registered a $1.04 billion operating surplus between 2020 and 2021, with an underlying surplus of $454 million.

The University of New South Wales (UNSW) reported a $306 million surplus last year, a considerable improvement from its $19 million loss in 2020.

The University of Technology Sydney recorded revenue amounting to $109 million, shading its $50 million loss from 2020 into oblivion.

Such surpluses suggest the viability of pay rises for staff, an important point in pay negotiations with stingy university managements.

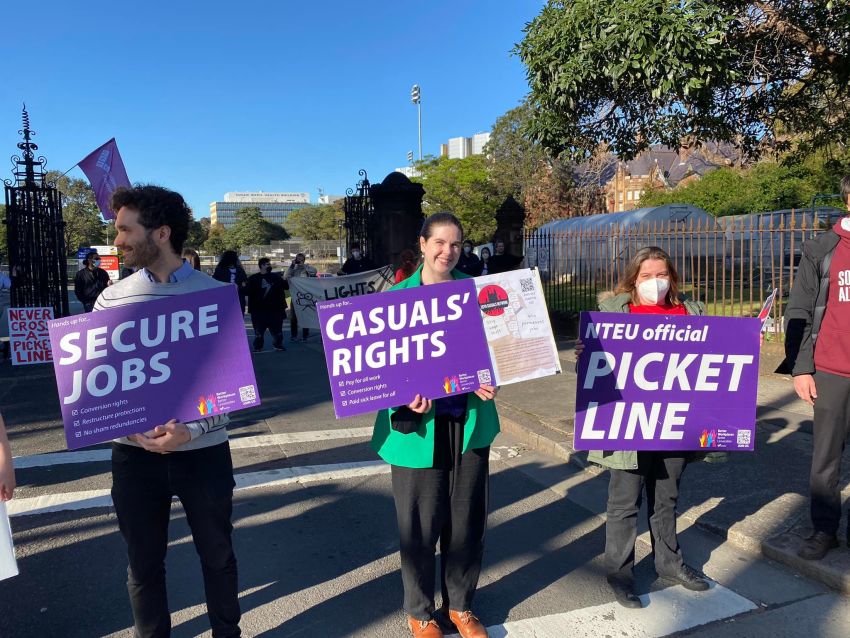

“There’s no excuse for university management to be hoarding money in such proportions,” reasoned the National Tertiary Education Union (NTEU) USyd branch president Nick Riemer. “People at the university are crying out for much-needed reforms. This shows they are affordable.”

NTEU New South Wales secretary Damien Cahill added his view that a number of universities, notably USyd, “can afford a fair pay rise for staff and to fix the problem of widespread job insecurity”.

The response from the administrators was characteristic: such ballooning surpluses were seen as one-off cases and around the corner, revenue-stripping disasters await. In other words, the pot of gold needed protection, not distribution.

USyd Vice Chancellor Mark Scott led the pack. “While this is a strong result, it is also a one-off result,” he claimed in May. “We are not immune from the continuing uncertain future of international higher education and the growing cost pressures currently affecting the global and Australian economies.”

The university’s 2021 annual report noted how the surplus came about: it was “mainly due to increases in overseas student enrolments, strong investment performance and non-recurring items including the Commonwealth Government’s $95.1 million Research Support Program contribution and the net gains from the disposal of property assets.”

The picture is one of corporate brands raking in cash rather than educators providing a public service.

Some 38 of Australian universities, for instance, drew revenue from selling their shareholdings in IDP Education, considered one of the world’s largest international education companies. Prior to the sale, universities held a 40% stake in IDP Education, retained via Education Australia.

While operating surpluses have been registered aplenty, job losses have been unremitting.

Thousands of staff have been given the big heave-ho, even as managers have continued feathering their nests. The latest federal government figures showed 3237 fewer permanent and fixed-term contract staff positions in 2021 than the year before.

UNSW topped the league tables, with 726 fewer full-time equivalent positions in 2021 than the previous year. USyd shed 223 staff, despite recording its best surplus in 172 years, a saving of $60 million from staff cuts.

To these job cuts can be added those suffered by the invaluable, long-suffering casual workforce. This precarious workforce, with minimal labour protections and economic security, constitute the vast bulk of the teaching staff.

Before the pandemic, the number of casual employees working in universities is estimated to have been about 100,000. The loss of 4258 full-time equivalents in 2020 were registered, but other higher assessments abound.

Before this spectacle of inequity basks the Australian Vice Chancellors, who receive inflated pay packages while they cut staff and continue precarious and unsustainable business model.

There needs to be an anti-corruption inquiry, to tease out the grounds for the ludicrous investment choices as well as the rules stifling free speech and academic freedoms.

Along the way, the habitual resort to non-disclosure agreements, the use of codes of conduct as silencing bludgeons and the almost total absence of solid anti-whistleblower provisions, should be looked at.

Instead of being interrogated by appropriate QCs, these managers only grow in number, undermining academic health at every turn and creating the next absurd “university” brand.

With each semester, new positions are created with names disturbingly reminiscent of industrial cleaning products: DVCs, PVCs and Deputy PVCs. These fatuous appointments are subsidised, in turn, by the labours of ailing, overworked staff, contemplating ruination, dejection and suicide.

The education system has been in sharp decline in inverse proportion to the financial returns being hailed. Without brave reforms that include decapitating the officialdom of university management, public money will be thrown after ill-gotten gains.

[Binoy Kampmark currently lectures at RMIT University.]