Since his kidnapping by Turkish military intelligence in Nairobi in 1999, Kurdistan Workers' Party (PKK) leader Abdullah Ocalan has endured almost 23 years of imprisonment. For much of that time he has been confined on Imrali island, in the Sea of Marmara, without any contact with family or friends.

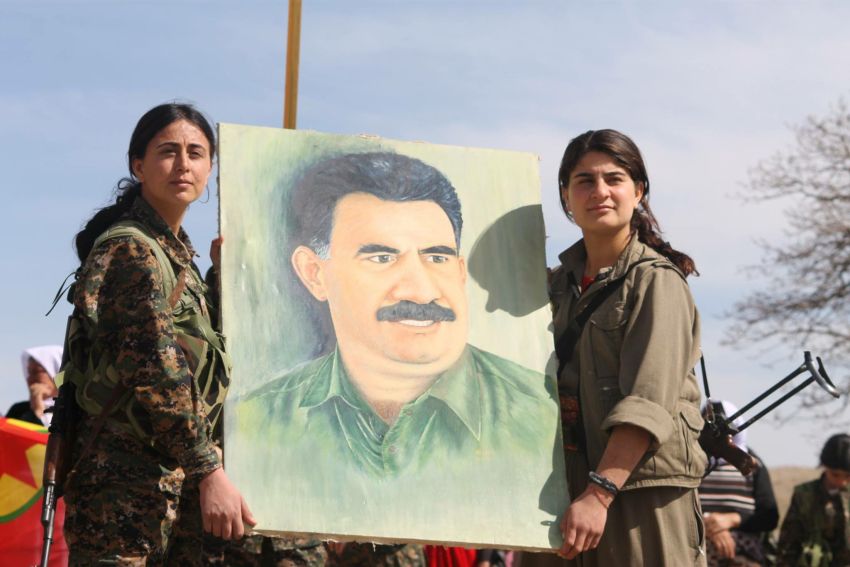

His jailers hoped that by slamming shut the prison doors, the world would forget about Ocalan’s existence. But for millions of Kurds and their supporters around the world, Ocalan is a living symbol of resistance to a century of oppression by the Turkish state.

According to the Turkish government, Ocalan is a terrorist. The Australian government agrees, listing the PKK as a terrorist organisation.

The listing was originally made in 2005 by the John Howard Coalition government after a visit by Recep Tayyip Erdogan, the autocratic Turkish leader. It has been periodically renewed since then, including by Labor governments. The listing was made for purely opportunistic political reasons. Government justifications simply do not add up.

The PKK is not and never was a threat to the security of Australia, nor that of any other outside of the Turkish state. Several European courts, including the highest Belgian court, have ruled that the PKK cannot be treated as a terrorist organisation. Instead, it is a party to an armed conflict with the Turkish state.

Under Ocalan’s leadership, the PKK launched an armed struggle against the Turkish state in 1984. It has since declared several unilateral ceasefires and, in 2013, Ocalan was permitted to join peace talks. He continues to advocate for a peaceful solution to an intractable conflict.

Originally formed as an orthodox Marxist-Leninist party with the aim of creating an independent Kurdish state, the PKK has since taken a different approach under Ocalan’s intellectual guidance. Ocalan argues that given the ethnic plurality of Turkey and the Middle East, the solution to the century-long oppression of the Kurds and other non-Turkish populations lies in what he calls “democratic confederalism” — autonomy with full rights for all peoples.

This shift did not, however, cause the Turkish government to back away from its determination to maintain Turkey as the ethnically pure political-cultural organism envisaged by Kemal Ataturk at the time of the inception of Turkish Republic in 1923. Ever since, the Kurdish people have endured cultural and, at times, physical genocide.

In recent times, the Erdogan government has stepped up repression inside and outside the boundaries of the Turkish state. Thousands of Kurds have been arrested and many killed, especially members of the pro-Kurdish Peoples’ Democratic Party. Cities in predominantly Kurdish areas have been bombed.

The Turkish military has also invaded and occupied the mainly Kurdish regions of Rojava in northeast Syria, ethically cleansing towns and cities and collaborating with Islamist terrorists, including Islamic State. The Kurdish-speaking Yazidis over the border in Iraq have also been targeted by Turkish troops.

Yet world governments and much of the media continue to avert their eyes from Turkey’s war crimes and crimes against humanity.

The Kurds have a well known saying that they "have no friends but the mountains". But they do have many friends around the world, including in trade unions, left-wing and green parties, and other organisations of civil society: people who have seen the injustice heaped on the Kurdish people and are determined to help end it.

Key to fighting such oppression is to demand governments take the PKK off the terror list and call for the immediate release of Ocalan, so that he can lead the struggle for peace with justice for the Kurdish people in Turkey and neighbouring states.

Prison has not broken Ocalan, nor stopped his brain from working. In his prison cell, he has written a stream of original books and articles dealing with many aspects of Kurdish freedom and broader human emancipation.

Central to this is his insistence that “a society can never be free without women’s liberation”. His watchword is that “you must believe before everything else that the revolution must come, that there is no other choice”.

[John Tully is a historian and activist with Australians For Kurdistan.]