This year marks 80 years since the United States Army Airforce plane Enola Gay flew over the densely populated city of Hiroshima and dropped the first atomic weapon used in wartime — the gun-type uranium-235 fission bomb “Little Boy”.

Three days later, a larger and more powerful implosion-type plutonium bomb “Fat Man” was dropped over Nagasaki.

Together, these atomic bombs killed between 150,000 and 246,000 people and devastated two cities. Shortly afterwards, imperial Japan surrendered unconditionally to the Allied powers.

Those seeking to justify the US’ bombing of Hiroshima and Nagasaki claim it ended the war with Japan and prevented a full-scale invasion of the mainland, thereby preventing a greater loss of life. But, in August 1945, Japan was already on the brink of surrender.

White historians tend to attribute victory over the “Yellow Peril” to patriotic US and Australian manhood. However, it was the widespread popular resistance to Japanese colonialism in mainland China that really brought the Japanese military to its knees.

By the time the bomb was dropped, Japan’s population, which had largely supported its aggression on the Asian continent, was war weary. Absenteeism in the factories supplying the imperial war machine was growing and when the Allies occupied mainland Japan after the surrender, they were mostly welcomed by the Japanese as liberators.

The US bombing of Hiroshima and Nagasaki did not bring about the end of the Asia-Pacific War. Instead, it was the opening salvo in a new Cold War.

After 1945, the US pitted itself against communism, in particular the Soviet Union, which claimed to represent that movement. The Cold War shaped the rest of the 20th century.

The US’ atomic bombing of Hiroshima and Nagasaki provoked a nuclear arms race, in which states on both sides of its ideologically defined frontier developed and tested ever more powerful weapons of mass destruction.

Cold War

The Soviet Union conducted its first successful nuclear weapons’ test in Kazakhstan in 1949. The British carried out theirs in the Montebello Islands, off Western Australia, in 1952.

These were closely followed by the US testing newer, even more destructive hydrogen bombs in 1952 and 1954. Not to be left behind in the race towards nuclear Armageddon, France joined the nuclear club in 1960 and China in 1964.

The military strategy that emerged was dubbed by its theoreticians with a moniker that indicated their self-consciousness of its insanity: Mutually Assured Destruction.

Wollongong’s miners, steelworkers and others had been fighting against militarism, imperialism and nuclear madness since the early 20th century.

The city’s first industrial workforce, coal miners who worked the rich escarpment seams, were influenced by the International Workers of the World. When Labor Prime Minister Billy Hughes proposed a referendum on conscription, to supply bodies for the killing fields of Europe, the miners’ lodges passed motions condemning the move. They fought vigorously against conscription, which led to a resounding 65% “No” vote.

After the war, in the 1930s, when the battle between socialism and barbarism intensified, the city recognised the growing threat of organised fascism. Australia’s wannabe Führers formed the New Guard to attack and harass workers’ and left meetings. At the time, Wollongong mayor William Louis Howarth (1864–1940) was derided as the “Mussolini of the South Coast”.

The Workers Defence Corp and the United Front Against Fascism were formed and fought a decisive battle with the New Guard in Crown Street. This was followed by a boycott of New Guard members’ businesses, which led to their rapid decline.

International brigade against fascism

Port Kembla steelworkers Jim McNeill and Joe Carter signed up as volunteers to the International Brigade to fight for the elected Republican Government of Spain against a fascist coup led by military officers, large landowners and Catholic reactionaries.

The local labour movement gave the Republican cause full support, including raising funds for Spanish relief.

Returning from Europe in 1938, McNeill and Carter were welcomed as heroes by a city where local waterside workers had refused to load the tramp steamer Dalfram with pig iron bound for Kobe, Japan, because they knew it would fuel the Japanese war machine in China.

The Lyons government and its attorney-general, the infamous “Pig Iron” Bob Menzies, wanted to appease Japan.

The Port Kembla wharfies and the labour movement, however, could see that the war materiel steel giant BHP (now Bluescope) was selling at a profit to Japan to kill and maim in Nanking and other Chinese cities, would return to Australia as bombs and bullets.

With the beginning of the Cold War, the peace movement regrouped around opposition to nuclear weapons. In March 1950, the international Partisans for Peace launched the Stockholm Appeal, a signature campaign calling for a ban on nuclear weapons. Opposition to nuclear weapons became a key theme in May Day marches in the 1950s.

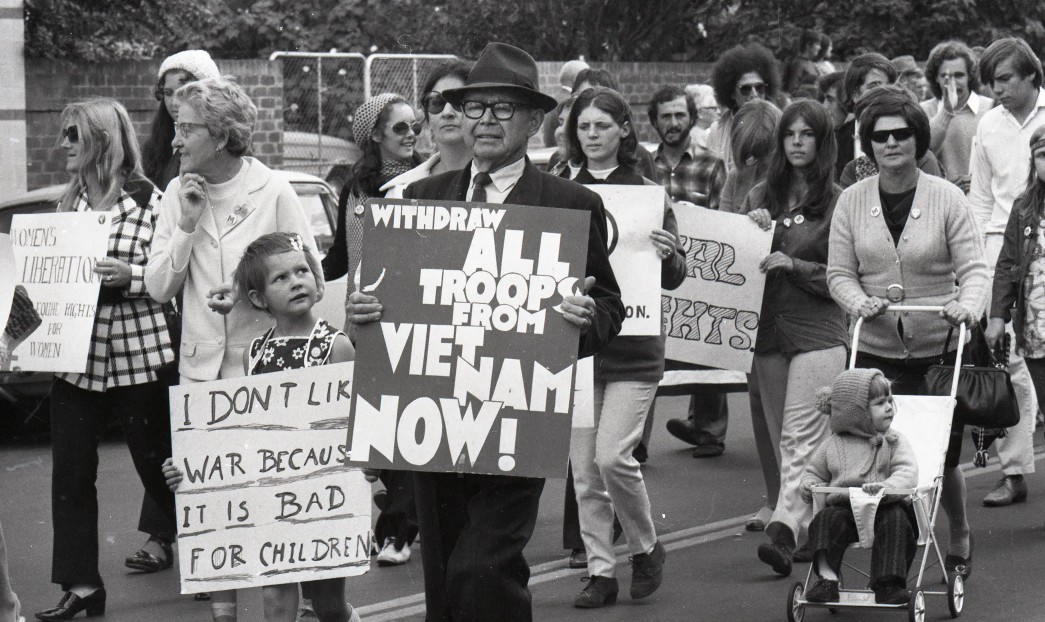

anti-war_march_1971_illwarra_mercury_image_collection.jpg

When the Cold War turned hot in Vietnam in the 1960s, young locals, such as Louie Christofides, took direct action. In April 1969, Christofides sat on the railway line at Wollongong Railway Station in front of a train carrying conscripts to Gadigal Country/Sydney for the war in Vietnam.

When Christofides was later jailed for refusing the draft, women, including his mother Helen and peace activist Sally Bowen, chained themselves to the railings of the public gallery in federal Parliament, seeking justice for Christofides and voicing their opposition to the war.

Nuclear disarmament

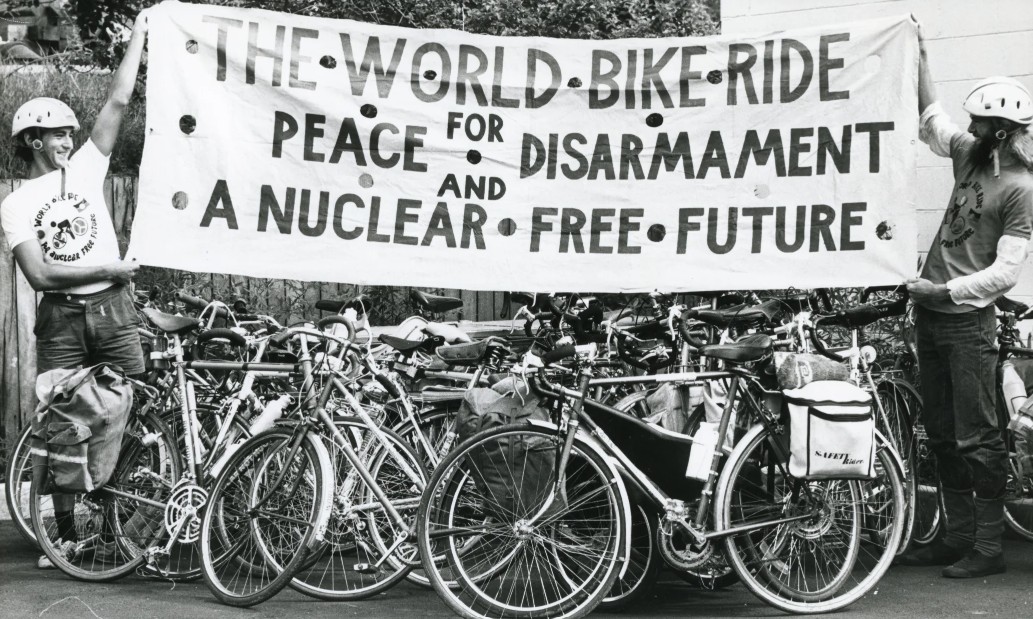

Following Australia’s withdrawal from Vietnam, between 1971 and 1973, anti-war activists directed their energies into the movement for nuclear disarmament.

The threat of atomic weapons loomed large in the 1980s, as sabre rattling between the US and the Soviet Union threatened to break out into nuclear war.

world_bike_ride_1982_illwarra_mercury_image_collection.jpg

Annual Hiroshima Day marches throughout these decades brought the peace movement together, culminating in 1986 with the United Nations International Year of Peace. Wollongong City Council convened the International Year of Peace Committee that year, and organised a civic commemoration of Hiroshima Day, installing a bronze plaque that remains at the corner of Crown and Church Streets.

I joined the Wollongong peace movement in 2001, following the 9/11 terrorist attacks against the US by Islamist group Al-Qaeda, itself a product of covert US operations during the Cold War.

The neoconservative George Bush administration used the attacks to launch a new global “War of Terror”, with the full support of Australia’s Liberal lap dog Prime Minister John Howard.

The peace movement mobilised against the new US attacks on Afghanistan, forming the Network Opposing War and Repression which, in February 2003, organised the largest peace demonstration in Wollongong’s history, with 5000 people in the streets.

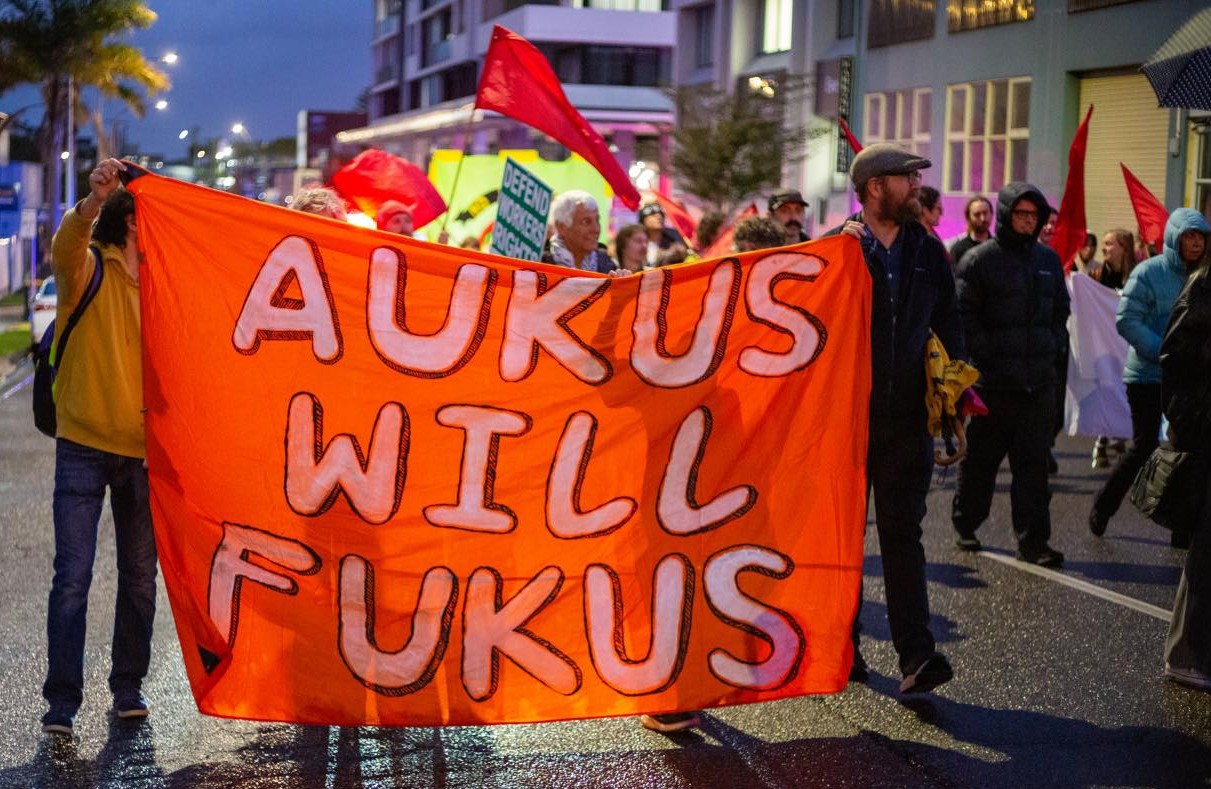

Opposition to AUKUS

Peace activists mobilised once more in 2022 under the banner of Wollongong Against War and Nukes, to protest the AUKUS military pact between Australia, Britain and the US, which included a possible east coast nuclear submarine base at Port Kembla.

AUKUS is built on hollow promises by the US and Britain to supply nuclear-powered submarines to Australia. Its true purpose is not to facilitate Australia’s purchase of a few second-hand radioactive death machines, but to deepen Australia’s involvement in the US’s forever wars.

wawan_mnarching_on_may_day_credit_wawan.jpg

The agreement covers technology transfers and the stationing of more US troops and US bases here, as well as the greater integration of Australia’s military under US command.

When Israel launched its most recent wave of genocidal violence against Palestinians in October 2023, a new generation of activists, deeply informed by decolonial and anti-racist politics, convened Wollongong Friends of Palestine.

The group has led a sustained campaign of protests, public meetings and direct action against Australian government support for Israel’s genocide.

Like the wharfies, who sought to halt Japanese military aggression, local opponents of Israeli aggression have fought the genocide in occupied Palestine by disrupting operations at local steelmaker Bisalloy Steels.

bisalloy_picket_unanderra_2024_nick_southall.jpg

Bisalloy profits by selling armoured steel to Elbit Systems, for use in armoured vehicles to kill, maim and oppress Palestinians.

We have seen an historic 18 months of uninterrupted weekly protest marches, and the movement continues to stand with Palestinians and other victims of Israeli aggression in the Middle East through a range of creative actions, including fortnightly protests, pickets, public meetings, school strikes and art and cultural activism.

Wollongong’s proud history of peace activism is currently being celebrated by Wollongong City Library in the Peace Movement Illawarra exhibition. It features physical displays of photographs and artifacts in the library and an online exhibition on the Illawarra Stories website.

You can find images commemorating the history of the peace movement and interviews with local peace activists Nick Southall, Gem Romuld, Sharon Callaghan, Margaret Perrott and myself, conducted by the library’s oral history volunteers.

[Alexander Brown will present a talk on history of the local peace movement as part of the Peace Movement Illawarra exhibition exhibition, on July 28 at 5pm at the Wollongong Library. He will also be performing some Japanese kamishibai at the library on August 2 at 11am, which is aimed at children and the young at heart, and will include a story about Hiroshima. There will also be a series of workshops to make origami peace cranes in various branches of the library. Wollongong Against War and Nukes will commemorate 80 years since the bombing of Hiroshima and Nagasaki and our continuing determination to end war with a lantern parade on August 9, 5pm, at Civic Plaza. This piece was first published at Alexander Brown’s blog The Gong.]