The size of the win of Prime Minister Viktor Orbán’s conservative-nationalist Fidesz party in the April 3 Hungarian general elections — in Orbán’s own words “such a victory that it can be seen from the moon, and, for sure, from Brussels”— didn’t in the end come as a surprise.

Orbán’s win was devastating for those who were hoping that the politically heterogeneous opposition bloc “United for Hungary” — combining liberals, social democrats, social liberals, greens and the ultra-nationalist Jobbik — might repeat its 51.1% to 44.9% victory over Fidesz in the 2019 Budapest council (assembly) election.

This time, however, 54% of the party list vote, which accounts on a proportional basis for 93 of the seats in the 199-seat Hungarian parliament, went to Orbán’s party.

Only 34.4% went to United for Hungary, whose lead candidate was Peter Márki-Zay, conservative Catholic independent and mayor of the southern city of Hódmezővásárhely.

The vote for the other 106 constituency seats, elected on a first-past-the-post basis, was 53.3% to 36.1% in favour of Fidesz.

Here Hungary’s rural gerrymander worked brutally in Orbán’s favour: Fidesz won 88 (83%) of these 106 constituency seats, including 98% of those outside Budapest.

The overall result was that Fidesz won 135 of the 199 seats — enough for it to impose constitutional changes — while United for Hungary won 56 and seven (elected with 6.1% of the vote) went to the Our Homeland Movement, founded by dissident Jobbik leaders who opposed that party’s abandonment of open xenophobia and antisemitism.

The last seat went to a representative of Hungary’s German minority.

The participation rate was 69.5%, nearly 20 percentage points higher than in the 2019 local government poll and the third highest since Hungary’s transition from “communism”.

Anti-LGBTI referendum torpedoed

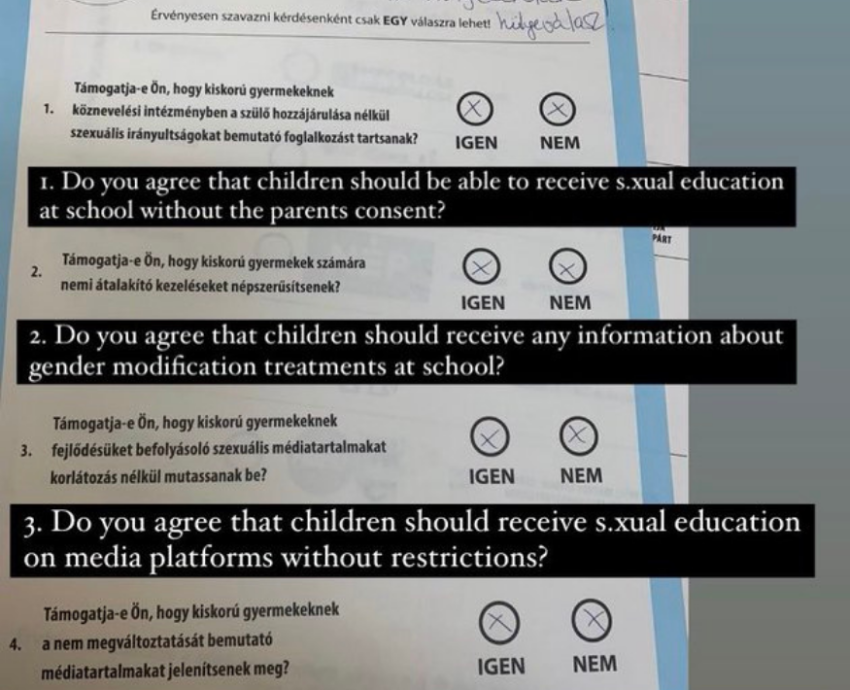

However, as if to prove that Hungary is not all black reaction, Orbán’s accompanying referendum, aimed at legitimising his reactionary stance on LGBTI rights, failed to achieve the 50% participation needed to make it valid.

Opponents of the referendum, which was posed as about “child protection”, ran a strong campaign to spoil the ballot, and succeeded in reducing the number of formal votes to less than 45% of those eligible.

Around 20% of ballots were spoiled, with the “spoilers” often sharing over social media their wittily abusive comments on their ballot paper.

More than 90% of the remaining formal votes voted “No” to the referendum’s four very loaded questions, such as “Do you support the unrestricted exposure of underage children to sexually explicit media content that may affect their development?”.

Victoria Rose, who does a Budapest drag show at night and also works as a maths and chemistry teacher, commented to the Canadian Broadcasting Commission’s Briar Stuart: “I find it really interesting that no-one has a problem with children being taught about sexuality as long as it is heterosexuality.”

The International LGBTI Association called the referendum an attempt at distraction from the Orbán government’s “gross failings and corruption”, while Rose commented: “This party [Fidesz] is always looking for enemies. First, it was the immigrants … and now it’s the gays.”

The null result of the referendum robs Orbán of the argument that he has the backing of the Hungarian people in his conflict with the European Commission and European courts over Hungary’s discriminatory laws, but his increased majority will embolden him to maintain the conflict with Brussels.

As happened after a similar null referendum in 2016, in which Orbán asked Hungarians to reject European Union member state quotas for receiving refugees, domestic policy on LGBTI rights will probably become crueller and more vindictive.

Reasons for a landslide

It was never going to be easy for the opposition to repeat its 2019 Budapest assembly win across Hungary as a whole.

Firstly, because the social and political divide between the capital and the rest of the country is deep. In 2019, the opposition won Budapest and 10 out of the 23 largest cities (up from three), but none of the 20 county councils covering all Hungary’s regions beyond the capital. The countrywide vote favoured Fidesz 54.5% to 41.6%.

Secondly, because — in the mild words of the preliminary report of observers from the Organisation for Security and Cooperation in Europe (OSCE) — the election was “well-run” but “marred by the absence of a level playing field”.

That “absence” is because Orban has been busy tilting the playing field in his favour ever since he was returned to government four elections ago, in 2010. By the time of this poll the Orbán regime had:

- Established tight control over all major public and private media. By 2017, around 90% of all media was owned by the state or a Fidesz supporter

- Redrawn the map of constituency seats to load opposition supporters into a handful of seats while spreading Fidesz voting support as widely as possible

- Refused to revise the boundaries of electorates that exceeded the deviation limit applying after the 2018 elections, further deepening the rural gerrymander

Orbán also refused to adopt an election funding law that would have ended “opacity of campaign funding” according to the OSCE, which allows third party funding that favours the government.

In 2020, on the pretext of the need to fund anti-COVID-19 measures, his government halved official electoral funding, which constrained the opposition but had no effect on Fidesz.

In addition, the OSCE reported that a March 1 Constitutional Court decision “effectively authorised the government to engage in election campaigning”.

The result was an election campaign in which there were no debates, vast amounts of government funded pro-Fidesz propaganda, while the opposition was constrained by spending limits.

According to Hungary’s anti-corruption agency, Fidesz displayed 12,171 campaign billboards, while the opposition managed 1564.

A doomed opposition

However, none of this means that Fidesz doesn’t have a sizeable (cross-class) social base, nor that Orban’s message of Hungary as victim — of the EU, international (usually Jewish) conspiracies and supposed historic injustices beginning with the Treaty of Trianon (1920) — doesn’t reverberate with many.

More important, however, has been the attention he has given to maintaining and increasing the value of social security payments and defending living standards.

A few months before the election Orban introduced an income tax rebate for families with children, a 13th-month pension payment, a minimum wage increase, exemption from income tax for under-25s, and a price freeze on fuel and some basic food items like flour, oil, sugar and chicken.

Moreover, if Fidesz was ever in danger of losing — at times until January the opposition was ahead in polls — its victory was sealed when Orbán successfully cast Hungary as a force for peace and stability in the Russia-Ukraine conflict.

Opposition leader Márki-Zay, thinking the path to victory was to align with the United States and EU, tweeted: “The stakes are clear — Orbán and Putin or the West and Europe.”

Orbán responded by posing as concerned most of all not to inflame the conflict or expose Hungary to danger. He supported EU sanctions against Russia but refused to allow weapons bound for Ukraine to pass through Hungary.

The opposition, painted as partisan warmongers, immediately fell in the polls as the war overtook its possibly winning issues — corruption, education, and health — as people’s greatest concern.

Yet the opposition had an even deeper problem. Adam Ramsay, writing in OpenDemocracy, summarised its performance: “By stretching their alliance to the far-Right party Jobbik, and anointing Peter Márki-Zay, a conservative, as candidate for prime minister, the opposition muted itself. Out of mutual desperation to rid the country of its increasingly autocratic ruler, they seemingly forgot to stand for anything.”

Hungarian Marxist author Tamás Krausz agreed: “Orbán — whom the opposition parties portrayed as a classical representative of capitalist banditry, corruption, and authoritarian state-power centralisation — in his social-populist way suggested a kind of security, unlike the chaotic opposition who wanted to win the elections with formerly failed liberal politicians.”

Orbán’s tone was given in his victory speech: “This victory will be remembered for the rest of our lives because so many people ganged up on us, including the left at home, the international left everywhere, the bureaucrats in Brussels, all the funds and organisations of the [George] Soros empire, the foreign media, and in the end even the Ukrainian president [who criticised Orbán’s closeness to Putin].”

Orbán’s first move after winning the election has been, statesmanlike, to call for an immediate cease-fire in the Ukraine and offer Budapest as location for peace talks.

[Dick Nichols is Green Left’s European correspondent, based in Barcelona.]