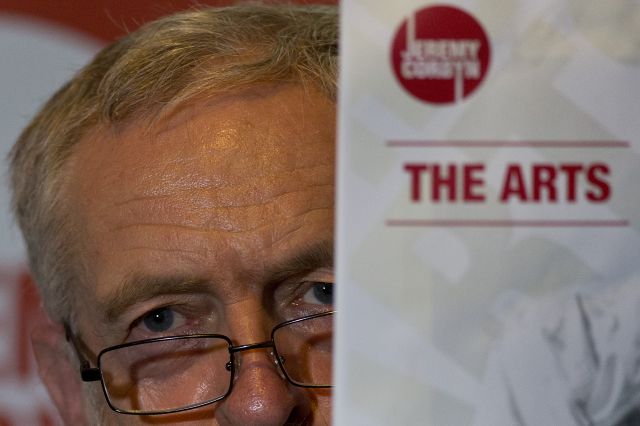

The recent election of socialist MP Jeremy Corbyn as leader of Britain’s Labour Party has spurred a flurry of debate on the left, particularly after the failure of anti-austerity SYRIZA to live up to its promise of standing up to Europe’s imposed memoranda.

Regardless of where we stand on the Labour Party generally, there is no denying that Corbyn’s victory has generated huge excitement and mobilised thousands of young people new to politics and seasoned Labour members alike.

And as Europe contends with a refugee and migrant crisis that is largely self-created through the West’s imperialist agenda, issues such as the arts and the state’s role in funding and supporting them were not the key headline.

Yet Corbyn noted that the question was important, and issued a statement on the topic: “The arts are for everybody, not the few; there is creativity in all of us.”

Corbyn blasted cuts to the BBC, the failure to get arts funding directly into the hands of performers and educators, and the “ruthlessly instrumentalist” approach of the Tories to assessing the contribution of publicly funded arts and arts education programs to our society.

Instead, he proposed an alternative vision: “We as a Labour party must offer an alternative program for the arts, both supporting their ability to enrich the cultural lives of hundreds of thousands of people every year across the UK and promoting a feeling of community ownership from which we all benefit.”

Corbyn’s recognition of the arts’ importance should drive us to think about why it is always the case that arts are the first to come under the axe of austerity.

Too often, it seems, we internalise the neoliberal line: that the arts, as much as we might like them, are not an essential part of the functioning of society — and they can be cut in the name of streamlining.

In this view, arts are aesthetic and not fundamental. Faced with the threat of seemingly inevitable cuts, many people quite understandably accept the arts as a sacrifice to protect funding for health care and food access programs.

After all, what person would demand to hold on to their publicly funded symphony if they were told doing so would result in hungry children?

It is time to reassert a different vision of the role that art and arts education play in society, and to take a decidedly political approach to their growth and defence.

Corbyn is absolutely right to demand not only funding for the arts and broadcasting, but also the placement of that funding directly into the hands of the people who best know how to use it: artists, performers, educators.

An anti-austerity arts program must also be anti-neoliberal. It must demand democratisation of the arts, which starts with the democratisation of funding.

This might also be a way to begin to dismantle the heavy NGO domination of the arts. After all, foundations do not know what kind of arts working class communities want and need. Board members do not know the best way for teachers to use arts to bring together immigrant and native-born children.

In calling for community ownership, there is a call to take ownership away from boards of directors.

All in all, it is an exciting time for the cultural left in Britain. What will be done with this opportunity? It’s too early to tell.

What is critical is that there is an alternative to austerity and that alternative can include the arts. In fact, it must. The arts are fundamental for understanding who we are, for coming to see ourselves as political beings.

How many people do you know were partially radicalised by an album like The Coup’s Kill My Landlord, or by a graphic novel like Marjane Satrapi’s Persepolis? And this is only in addition to the less tangible way that art, and particularly public art — murals, statutes, street music, radio — shape our politics and horizons.

The arts play an important part in shaping our ability to fight back. They — as expressed in songs like African American musician Janelle Monae’s “Hell You Talmbout” about Black people killed by racist police — help give us collective voice.

Most fundamentally, public arts can help establish the existence and dignity of the workers and the marginalised without relying on the support of ruling class patrons.

In other words, arts are not the first thing to face cuts because they are superfluous. Instead, the targeting of the arts is a strategic ruling class attack meant to undermine our dignity, our humanity and our ability to fight back. And for that reason, even in this time of crisis, and even when human misery grows in every direction, the arts must be a part of our vision for the future.

Because we don’t want to simply survive or exist. We want to live.

[Abridged from Red Wedge.]

Like the article? Subscribe to Green Left now! You can also like us on Facebook and follow us on Twitter.