Most people would know about the Aboriginal Tent Embassy, set up in 1972 outside old Parliament House in Canberra.

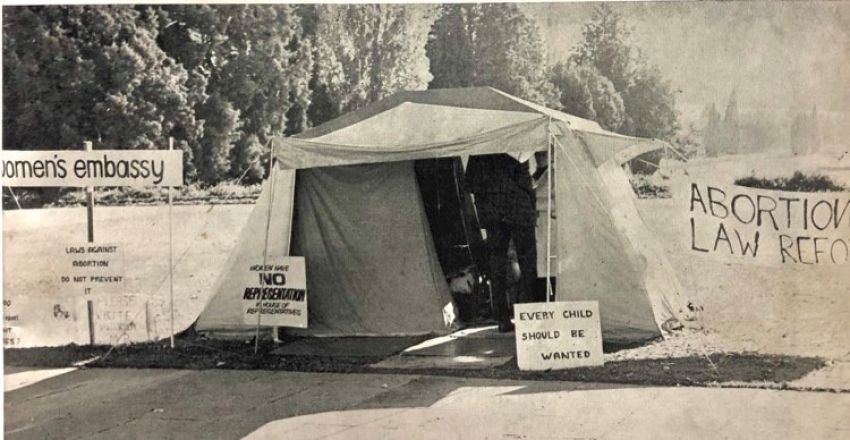

But few would have heard of the Women’s Embassy, set up in at the same place, on May 1, 1973. This was the first action of the Women’s Abortion Coalition Group, which Inge Disney writes about in the Autumn 1974 edition of The Australian Humanist.

Disney described how soon after the women erected their tent, friends arrived with groceries, blankets, chairs and hot coffee.

The struggle for abortion law reform had officially begun in Australia.

They nominated a spokesperson, alerted the media and waited for the onslaught. It came. The first day, there was a queue to sign the petition that lasted up to 11pm. They began to realise just how much support there was for their campaign.

The activists’ children loved it: sleeping on air beds in a tent and riding tricycles around parliament’s lawns.

The action group gave away masses of literature, including questionnaires, the aims of the Abortion Law Reform Association, car stickers and a booklet titled, What every woman should know.

The embassy was a stunt to gain coverage for the Abortion Law Reform Association, which was campaigning for reproductive rights for women.

The tent allowed the activists to reach out to teenagers and high-school students, desperate for reliable and non-judgemental information on sex and contraception, facts about venereal disease and, of course, abortion.

After three days, the women began to receive mail delivered to “The Embassy”, the “Woman in Charge” or, simply, “The Tent”.

Letters, cards and telegrams poured in, together with donations, messages of good luck and thanks. There was some abuse from men, some violent, but that was a minority.

By 1973, abortion and shot-gun marriages had reached epidemic proportions. Disney was asked many times why she was at the Woman’s Embassy.

Her reply was personal: “I was an unwanted child and I had a very unhappy childhood, much of which I do not remember. But what I do remember is so unpleasant, that I will do all in my power to prevent another child from going through a similar experience.

“I was brought up from the age of two in Catholic convents and it was not until I was nearly 30 that I began to throw off the effects of this plus, of course, the attentions of an unwilling father who beat me after I left the convent.

“My background was not a one-hundredth part as bad as that of some children with whom I have worked since. These children, deprived, neglected and so cruelly treated that they often end up psychotic, literally driven mad by the cruel treatment of parents and guardians, are the real victims of a society that had children as a matter of convention, not as a well-reasoned choice.

“Even so I still feel that my background was bad enough for me to be aware of the damage that physical and emotional cruelty can cause. My personal credo is as simple as the message on our car-stickers: ‘Every child should be wanted.’”

The day David Mackenzie and Tony Lamb introduced their abortion law reform bill — Medical Practice Clarification Bill — to the House of Representatives, a huge lunch-time crowd came to show their support.

However, the Right to Life organisation organised 1000 people, bussed in from interstate, to be present and they erected a marquee on the opposite side of the parliamentary lawns.

If passed, Mackenzie and Lamb’s bill would have allowed abortion in the Australian Capital Territory. However, it was defeated by 98 votes to 23 on a "conscience vote" on May 10, 1973.

Disney also describes how Kep Enderby, then a Labor MP, helped her set up the tent after a night of “ever-present” wind. “His support has been invaluable,” she wrote.

Abortions were being performed, however, but only for those who could afford it and had a friendly doctor. Some people even flew to Hong Kong or Japan for their abortion. Poor women had no other choice but to find backyard abortionists, with all the attendant dangers.

Vince Gair, then leader of the conservative Democratic Labour Party and a Queensland Senator, demanded the tent embassy be removed, asking parliament how long “that eyesore” would be allowed to remain. Enderby replied that he had no intention of removing the tent. Removing it, he said, “would not prevent the women from giving up their fight for the just liberalisation of the abortion laws”.

Disney blamed doctors, religious bodies, and senior figures in the Liberal and Labor parties who fought tooth and nail against releasing information on contraception.

Who would have thought, back then, that it would take so long for state governments to remove abortion from various crimes acts and legislate for a basic human right?

It took another 45 years of struggle for abortion to be removed from the Queensland crimes act, in 2018, and 46 years in New South Wales.