Official statements about the AUKUS security pact between Washington, London and Canberra rarely mention the target. Instead, they talk up “new strategic environment”, “great power competition” and “rules-based order”.

So the occasional burst of candour from United States diplomats provides a striking difference to their Australian and British counterparts.

Kurt Campbell, US Deputy Secretary of State, was refreshingly frank during his April 3 visit to Washington’s Center for a New American Security (CNAS).

Campbell is US emissary in the Pacific since AUKUS was announced in September 2021.

Campbell, as Deputy Assistant to the US President and Coordinator for the Indo-Pacific, was busy unfurling the US flag in various Pacific states in March last year, saying US policy was moving from neglect to greater attentiveness.

The Solomon Islands, given its newly minted security pact with Beijing, was of special concern to him.

“We realise that we have to overcome in certain areas some amounts of distrust and uncertainty about follow through,” Campbell explained to reporters in Wellington, New Zealand.

“We’re seeking to gain that trust and confidence as we go forward.”

In Honiara, Campbell conceded that the US had not done “enough before” and had to be “big enough to admit that we need to do more, and we need to do better”.

This entailed, in no small part, cornering the Solomon Islands Premier Manasseh Sogavare into affirming that Beijing would not be permitted to establish a military facility capable of supporting “power projection capabilities”.

In his discussion with Richard Fontaine, CNAS Chief Executive Officer, Campbell explained that “the United States and other nations confront a challenging security environment” and that “the best way to maintain peace and security is to work constructively and deeply with allies and partners”.

A rebuke was reserved for those who think “that the best that the United States can do is to act alone and to husband its resources and think about unilateral, individual steps it might take”.

The latter view has always been scorned by those calling themselves multilateralists, a term for waging war, arm-in-arm with satellite states and vassals, while ascribing to it peace-keeping purposes in the name of “stability”.

Campbell argued “that working closely with other nations, not just diplomatically, but in defensive avenues [emphasis added], has the consequence of strengthening peace and stability more generally”.

The virtue with the unilateralists is the possibility that war should be resorted to sparingly. If one is taking up arms alone, a sense of caution can moderate the bloodlust.

Campbell revealingly envisages “a number of areas of conflict and in a number of scenarios that countries acting together” in the Indo-Pacific, including Japan, Australia, South Korea and India.

“I think that balance, the additional capacity will help strengthen deterrence more general [sic].”

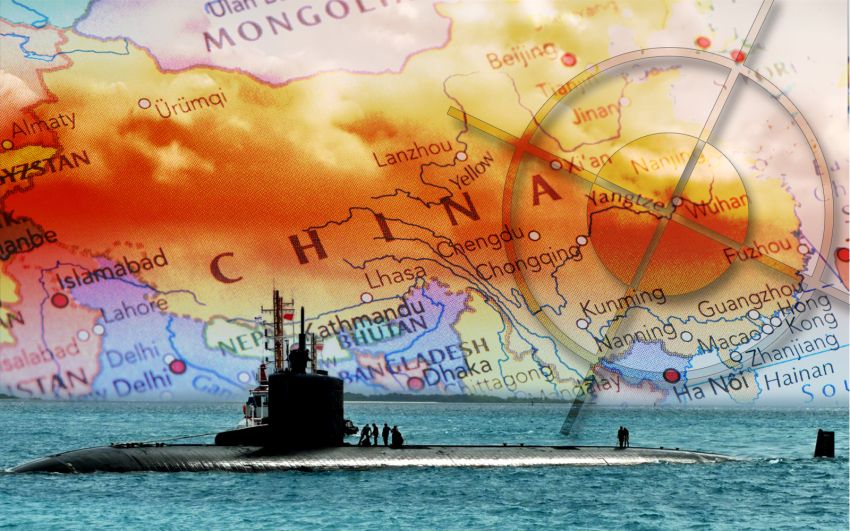

He also gave a candid admission on the role played by the AUKUS submarines: “AUKUS has the potential to have submarines from a number of countries operating in close coordination that could deliver conventional ordinance from long distances.

“Those have enormous implications in a variety of scenarios, including in cross-strait circumstances”.

Campbell spells out the prospect of submarines associated with the AUKUS compact being engaged in a potential war with China over Taiwan.

When asked on what to do about the slow production rate of submarines on the part of the US Navy necessary to keep AUKUS afloat, Campbell acknowledged the constraints — the COVID-19 pandemic, supply chain issues, the number of submarines in dry dock requiring or requiring servicing.

But undeterred, he insists that “the urgent security demands in Europe and the Indo-Pacific require much more rapid ability to deliver both ordinance and other capabilities”.

To do so, the military industrial complex needs to be broadened. “I think probably there is going to be a need over time for a larger number of vendors, both in the United States in Australia and Great Britain, involved in both AUKUS and other endeavours.”

There was also little by way of peace talk in Campbell’s confidence about the April 11 trilateral Washington summit between the US, Japan and the Philippines, following a bilateral summit between US President Joe Biden and Japan’s Prime Minister Fumio Kishida.

When terms such as “modernise” and “update” are bandied about in the context of an alliance, notably with an eye towards a rival power’s ambitions, the warring instincts must surely be stirred.

In the language of true encirclement, Campbell envisages a cooperative framework that will “help link the Indo-Pacific more effectively to Europe” while underscoring “our commitment to the region as a whole”.

A remarkably perverse reality is in the offing regarding AUKUS.

In terms of submarines, it will lag, possibly even sink, leaving the US and, to a lesser extent Britain, operating their fleets, as Australians foot the bill and provide the refreshments.

Campbell may well mention Australia and Britain in the context of nuclear-powered submarines, but it is clear where his focus is: the US program “which I would regard as the jewel in the crown of our defense industrial capacity”.

Not only is Labor effectively promising to finance and service that, it does so knowing of a potentially catastrophic conflict.

This is a high price to pay to abdicate sovereignty for the fiction of regional stability.

[Binoy Kampmark currently lectures at RMIT University.]